Содержание

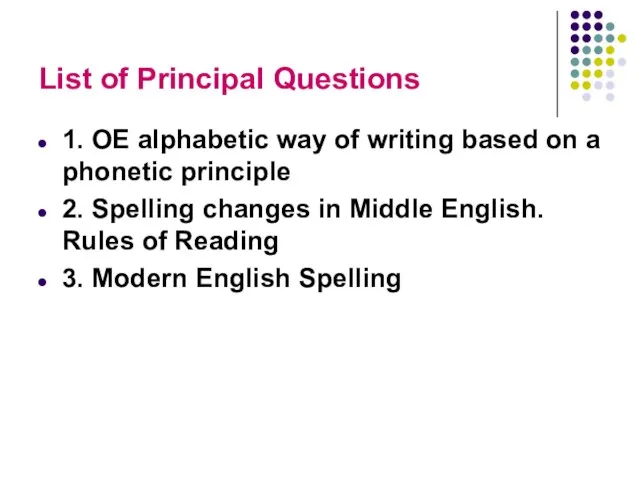

- 2. List of Principal Questions 1. OE alphabetic way of writing based on a phonetic principle 2.

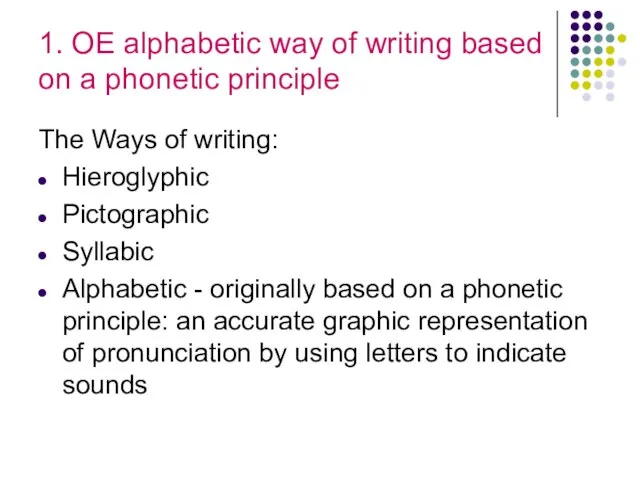

- 3. 1. OE alphabetic way of writing based on a phonetic principle The Ways of writing: Hieroglyphic

- 4. OE spelling a separate letter for each distinct sound the sound values of the letters were

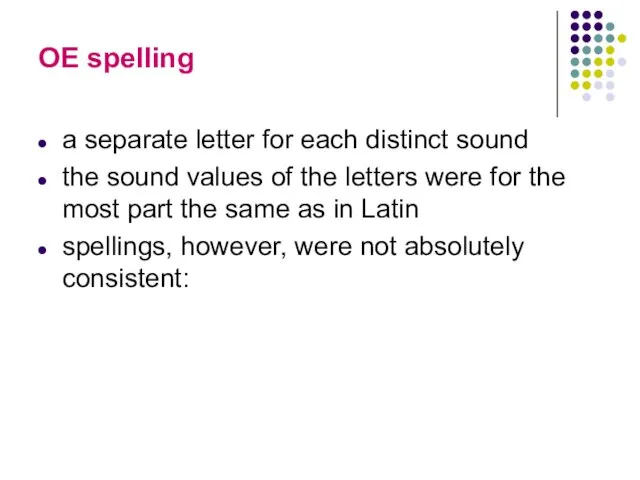

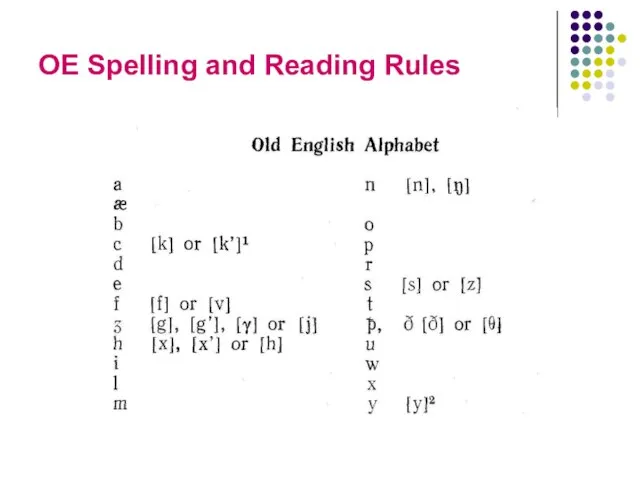

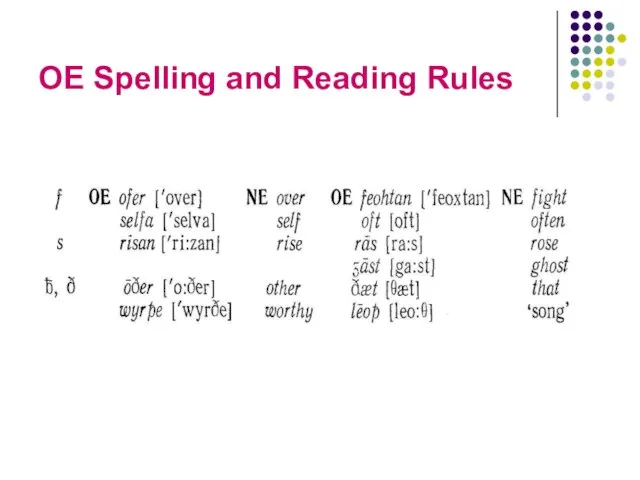

- 5. OE Spelling and Reading Rules

- 6. OE Spelling and Reading Rules

- 7. OE Spelling and Reading Rules OE ʒān [g], ʒēar [j], dæʒ [j], daʒas [γ], secʒan [gg]

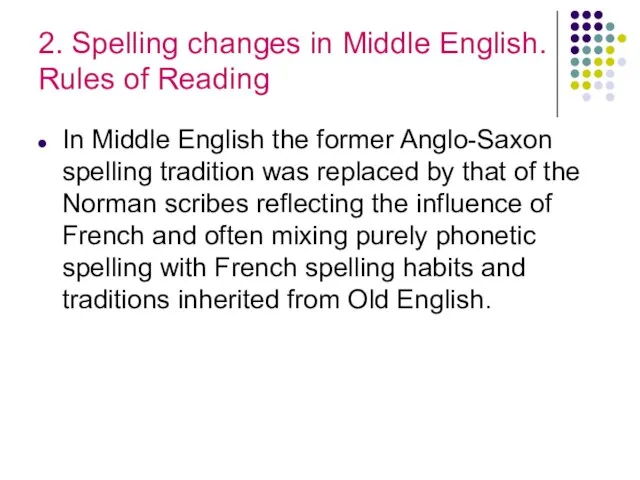

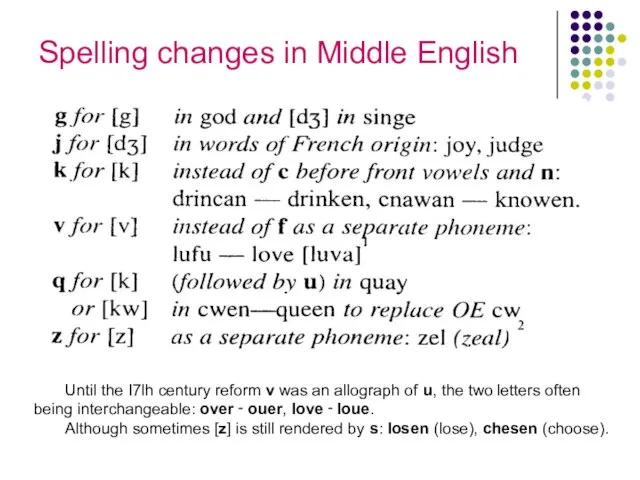

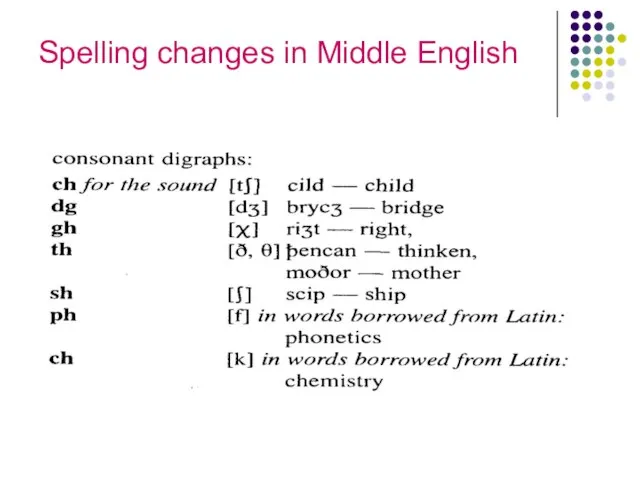

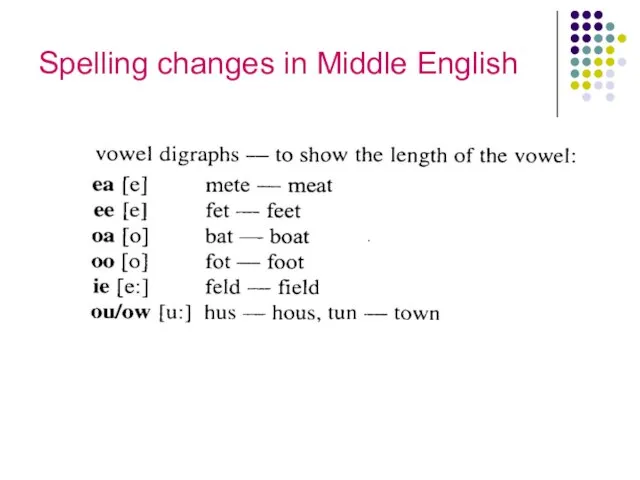

- 8. 2. Spelling changes in Middle English. Rules of Reading In Middle English the former Anglo-Saxon spelling

- 9. Spelling changes in Middle English

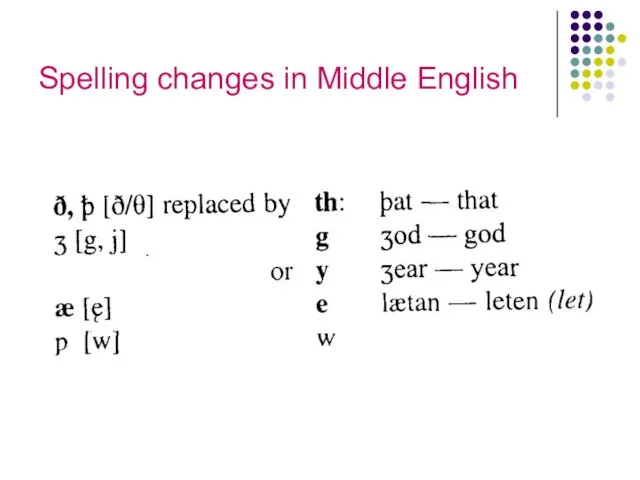

- 10. Spelling changes in Middle English Until the I7lh century reform v was an allograph of u,

- 11. Spelling changes in Middle English

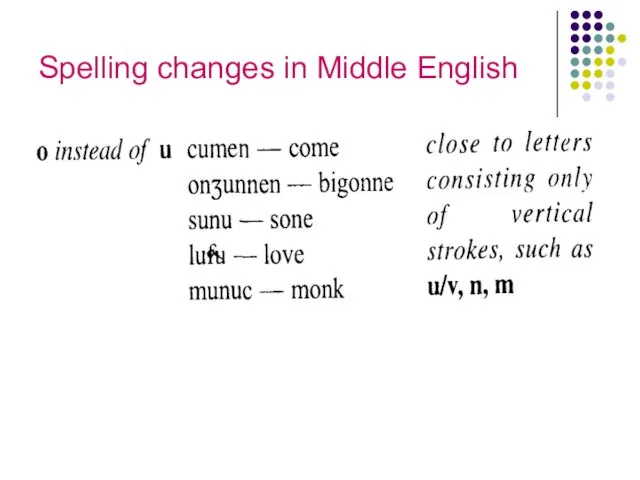

- 12. Spelling changes in Middle English

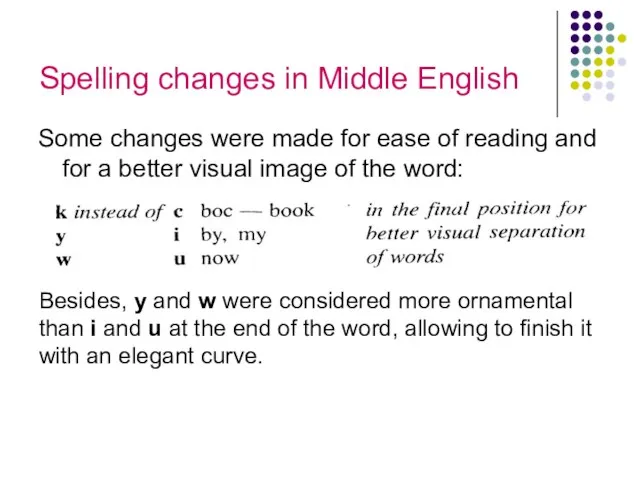

- 13. Spelling changes in Middle English Some changes were made for ease of reading and for a

- 14. Spelling changes in Middle English

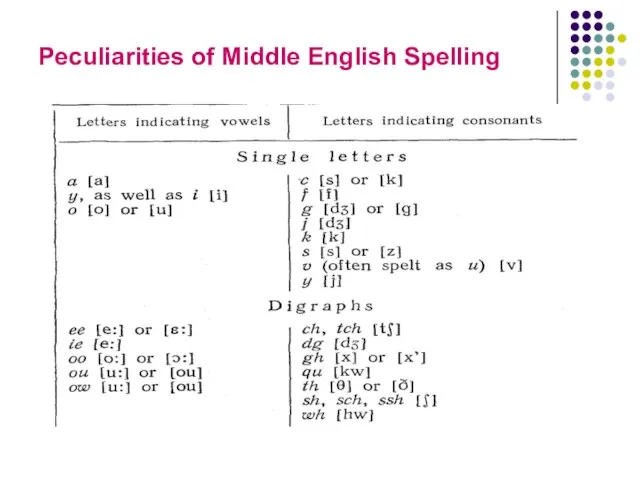

- 15. Peculiarities of Middle English Spelling

- 16. Peculiarities of Middle English Spelling G and с: [ʤ] and [s] before front vowels;[g] and [k]

- 17. Peculiarities of Middle English Spelling O = usually [u] next to letters whose shape resembles the

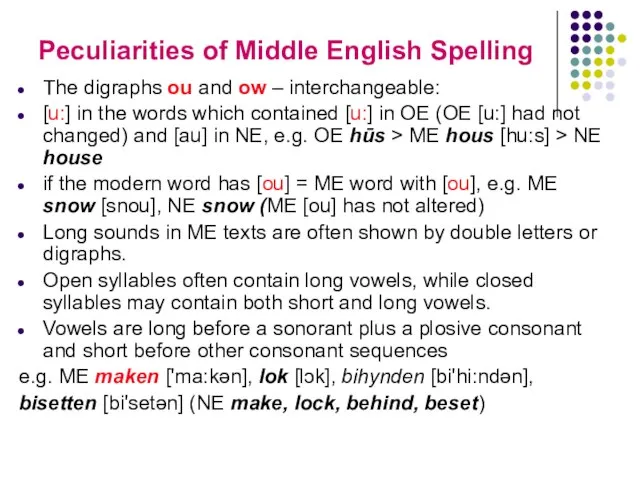

- 18. Peculiarities of Middle English Spelling The digraphs ou and ow – interchangeable: [u:] in the words

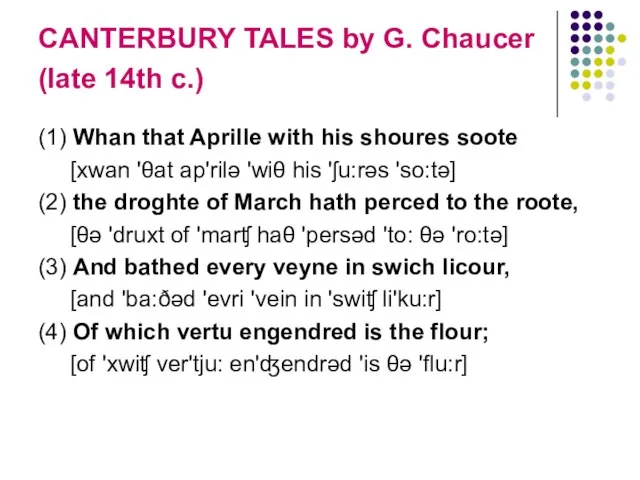

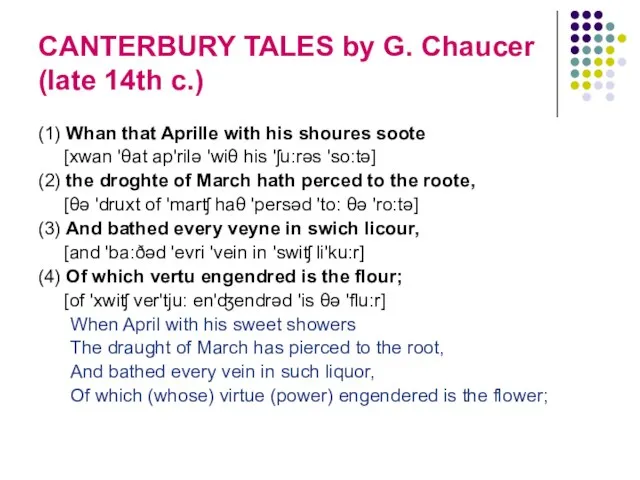

- 19. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (1) Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

- 20. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (1) Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

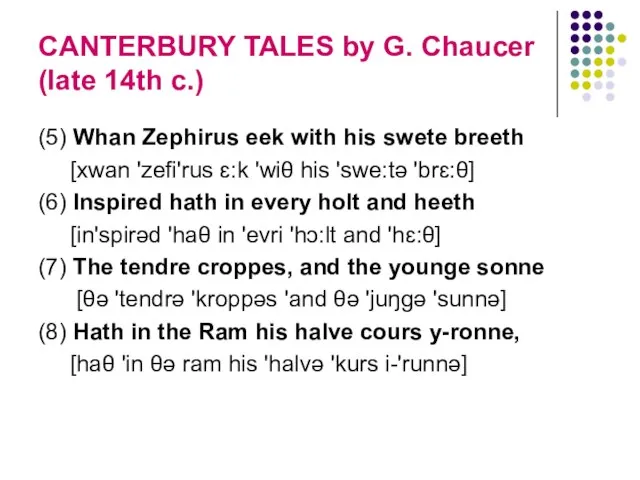

- 21. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (5) Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

- 22. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (5) Whan Zephirus eek with his swete breeth

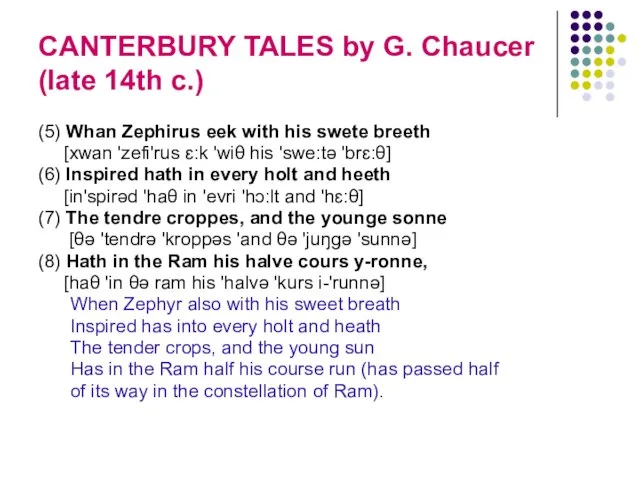

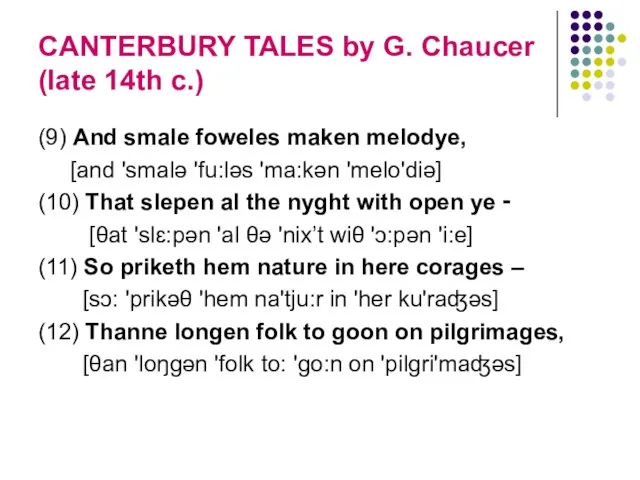

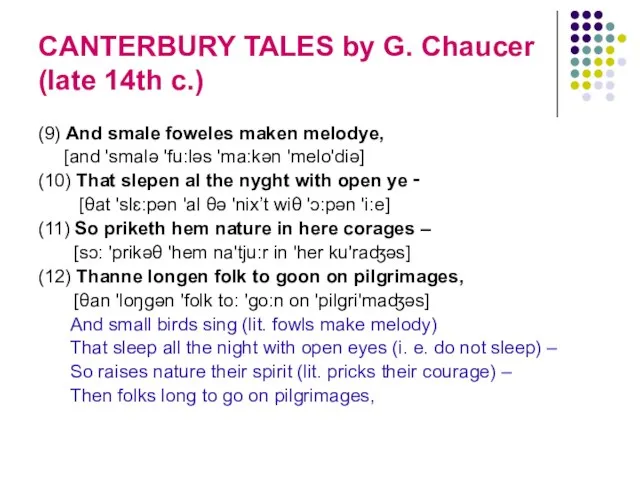

- 23. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (9) And smale foweles maken melodye, [and 'smalə

- 24. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (9) And smale foweles maken melodye, [and 'smalə

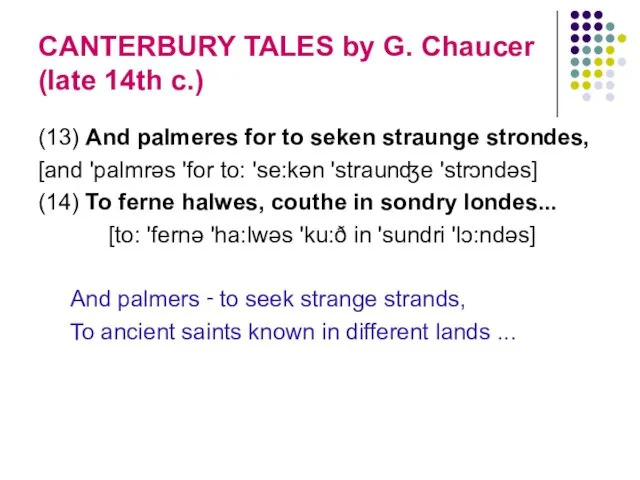

- 25. CANTERBURY TALES by G. Chaucer (late 14th c.) (13) And palmeres for to seken straunge strondes,

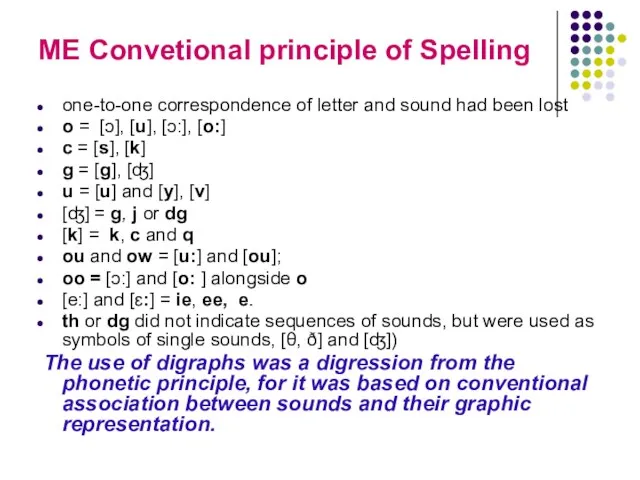

- 26. ME Convetional principle of Spelling one-to-one correspondence of letter and sound had been lost o =

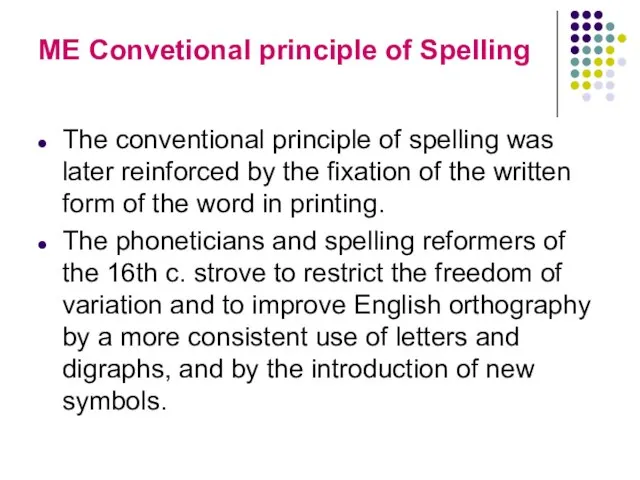

- 27. ME Convetional principle of Spelling The conventional principle of spelling was later reinforced by the fixation

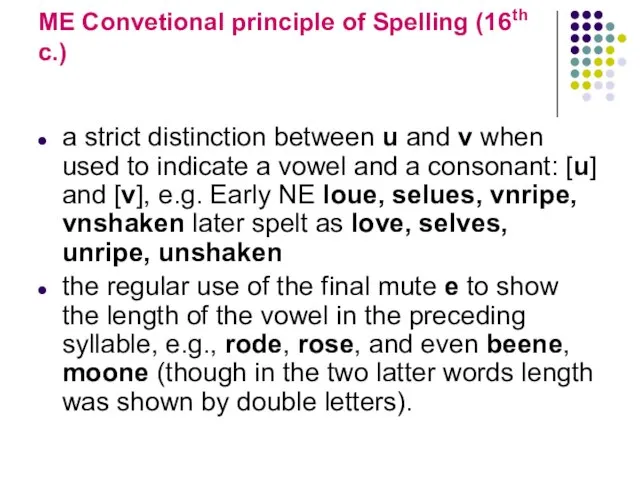

- 28. ME Convetional principle of Spelling (16th c.) a strict distinction between u and v when used

- 29. The phoneticians and spelling reformers of the 16th с. introduced new digraphs: ea = [ɛ:] e,

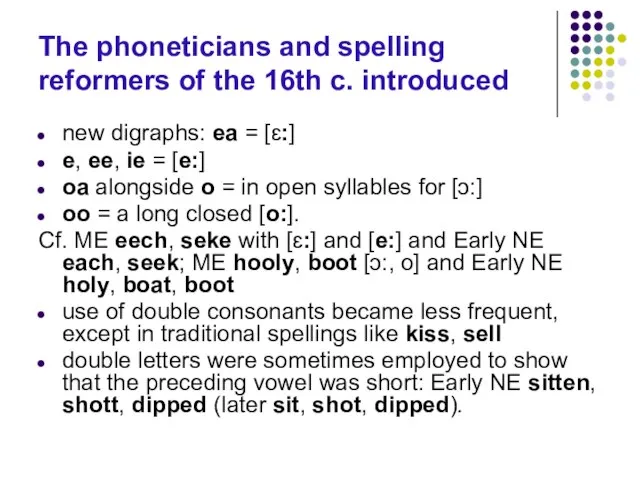

- 30. The activities of the scholars in the period of normalisation ‑ late 17th and the 18th

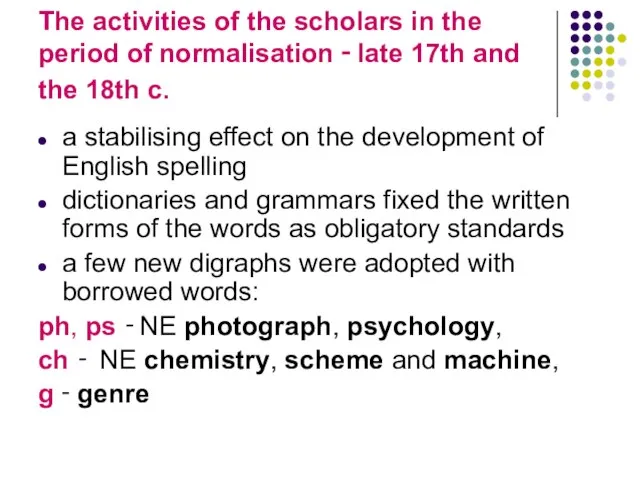

- 31. Modern English Spelling modern spelling is largely conventional and conservative, but seldom phonetic 16th c.: a

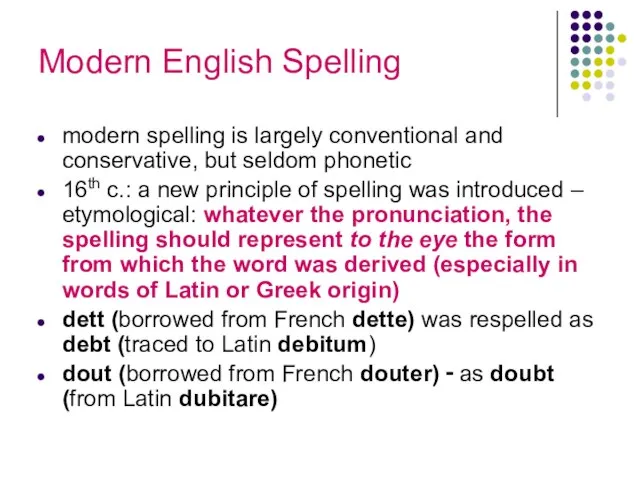

- 32. The so-called etymological spellings ME ake (from OE acan) respelt as ache from a wrongfully supposed

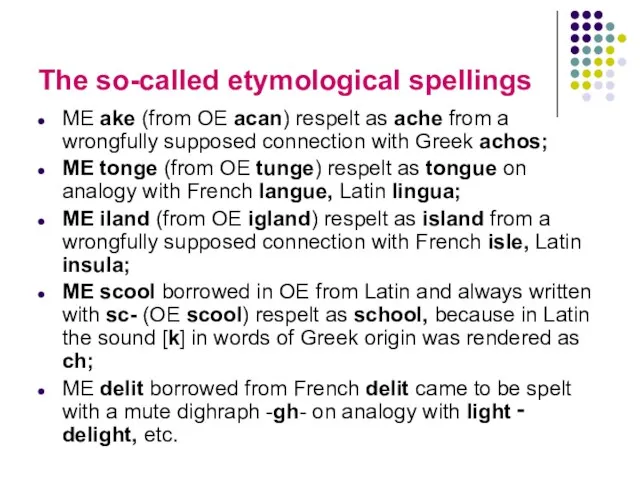

- 33. Modern English Spelling In the present-day system one sound can be denoted in several ways: [ɜ]

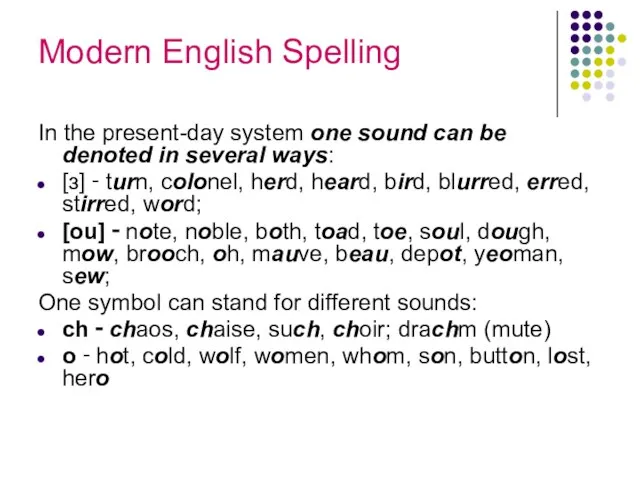

- 34. Many so-called “silent letters”can be explained only historically: e (mute e) at the end of words:

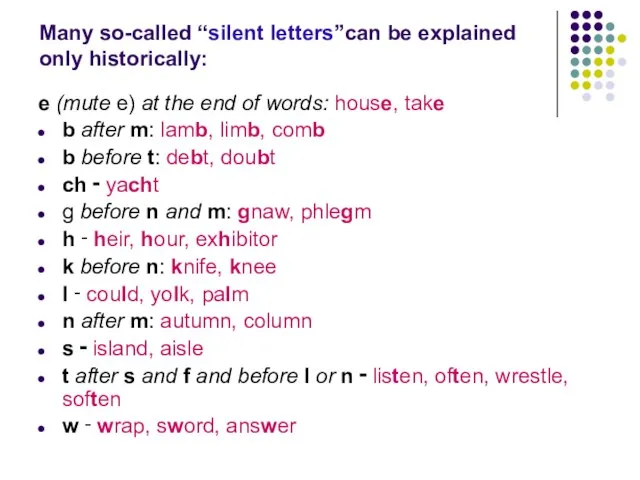

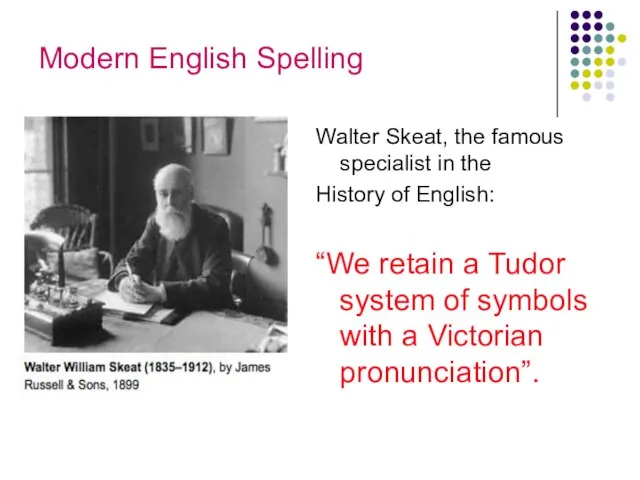

- 35. Modern English Spelling Walter Skeat, the famous specialist in the History of English: “We retain a

- 36. Walter W. Skeat

- 37. Main Historical Sources of Modern spellings (Short Monophthongs)

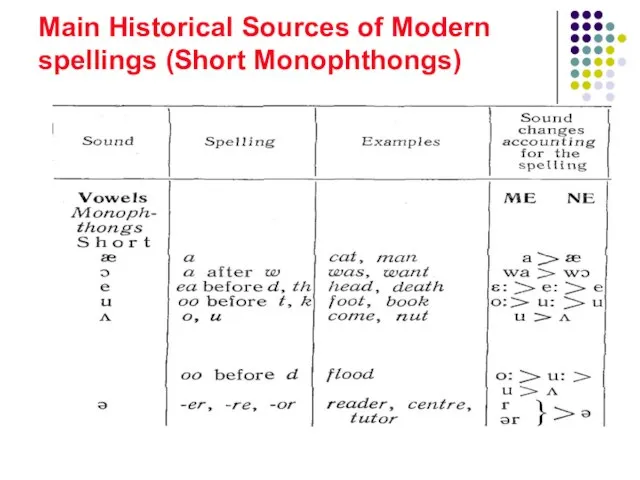

- 38. Main Historical Sources of Modern spellings (Long Monophthongs)

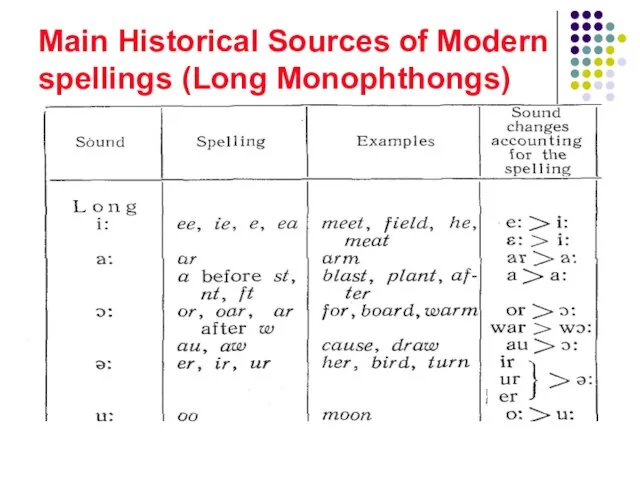

- 39. Main Historical Sources of Modern spellings (Diphthongs)

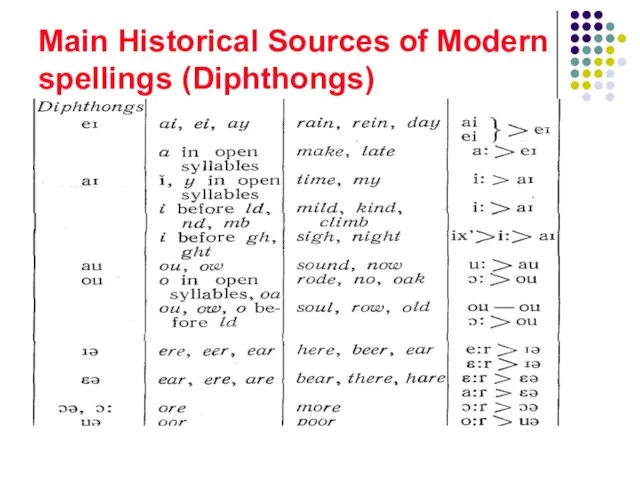

- 40. Main Historical Sources of Modern spellings (Triphthongs)

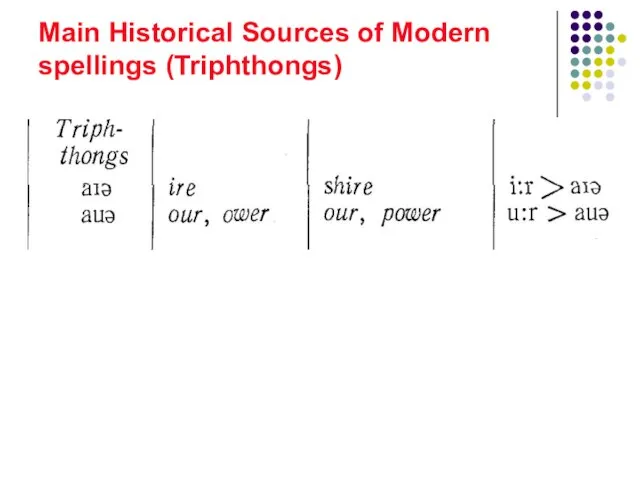

- 42. Скачать презентацию

![OE Spelling and Reading Rules OE ʒān [g], ʒēar [j], dæʒ [j],](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/378352/slide-6.jpg)

![Peculiarities of Middle English Spelling G and с: [ʤ] and [s] before](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/378352/slide-15.jpg)

![Peculiarities of Middle English Spelling O = usually [u] next to letters](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/378352/slide-16.jpg)

Воскресение Христово (Пасха)

Воскресение Христово (Пасха) Выполнили: студентки группы 41Д Артеменко Анастасия Журавлева Ирина Руководитель Банникова В.Г.

Выполнили: студентки группы 41Д Артеменко Анастасия Журавлева Ирина Руководитель Банникова В.Г. Операционные среды, системы и оболочки

Операционные среды, системы и оболочки Разработка установки для создания тонких пленок методом ионного наслаивания

Разработка установки для создания тонких пленок методом ионного наслаивания Исторические личности в повести А.С.Пушкина «Капитанская дочка»

Исторические личности в повести А.С.Пушкина «Капитанская дочка» Определения и свойства алгоритмов

Определения и свойства алгоритмов Презентация на тему Ферменты. Витамины. Гормоны

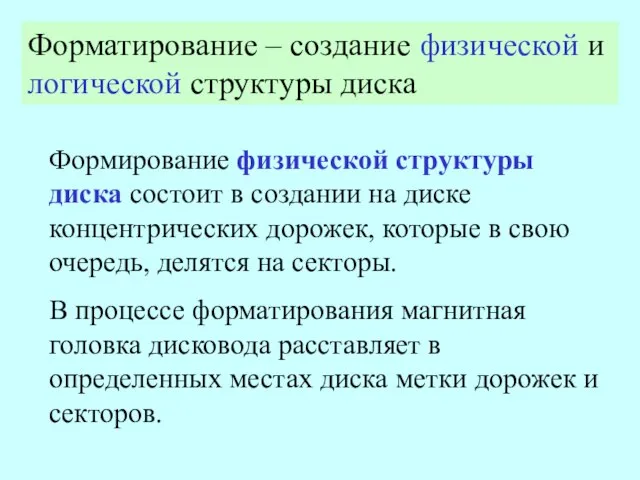

Презентация на тему Ферменты. Витамины. Гормоны Форматирование создание физической и логической структуры диска

Форматирование создание физической и логической структуры диска Тренажёр по краеведению. Мир природы.Полезные ископаемые.

Тренажёр по краеведению. Мир природы.Полезные ископаемые. Решение линейных уравнений

Решение линейных уравнений www.it-izhevsk.ru

www.it-izhevsk.ru  Задачи принцессы Турандот

Задачи принцессы Турандот Польза и вред компьютера

Польза и вред компьютера Обучающая площадка

Обучающая площадка Культура Кубани в 20-е годы

Культура Кубани в 20-е годы Презентация на тему О правах - играя

Презентация на тему О правах - играя Сведения об использовании цифровых технологий и производстве связанных с ними товаров и услуг

Сведения об использовании цифровых технологий и производстве связанных с ними товаров и услуг Брестский государственный профессионально-технический колледж торговли

Брестский государственный профессионально-технический колледж торговли Pros and Cons of Different Media

Pros and Cons of Different Media 20141003_viktorina_po_kraevedeniyu_1_chast

20141003_viktorina_po_kraevedeniyu_1_chast Декоративно-прикладное искусство. Часть 1

Декоративно-прикладное искусство. Часть 1 Искусство и духовная жизнь

Искусство и духовная жизнь Аверьянов В.Н. – первый заместитель министра здравоохранения Оренбургской области

Аверьянов В.Н. – первый заместитель министра здравоохранения Оренбургской области Кредитный портфель по розничному бизнесу филиала Челябинский

Кредитный портфель по розничному бизнесу филиала Челябинский От иконоскопа до плазмы

От иконоскопа до плазмы Школьная форма от компании Алфавит, цвет синий

Школьная форма от компании Алфавит, цвет синий Самовыражение в цвете

Самовыражение в цвете Информационно-консультационный центр поддержки СМиСБ при АОП РБ 243-38-37, 264-62-90

Информационно-консультационный центр поддержки СМиСБ при АОП РБ 243-38-37, 264-62-90