Содержание

- 2. Project Plan Introduction 01 The ‘Times of Troubles’ First Phase 02 End of Rurik dyansty 2nd

- 3. The age of transformation began with acute crisis–the ‘Time of Troubles’ (smutnoe vremia). This crisis begin

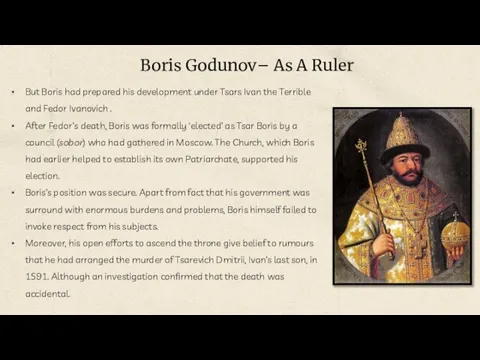

- 4. But Boris had prepared his development under Tsars Ivan the Terrible and Fedor Ivanovich . After

- 5. Boris was unable to consolidate power after accession to the throne. His attempt to tighten control

- 6. In autumn 1601, however, Boris’s government had to retreat and reaffirm the peasants’ right to movement:

- 7. The general sense of catastrophe mounted, rumours suddenly spread that Tsarevich Dmitrii had not died at

- 8. Above all, the Polish presence exposed old Russian culture to massive Western influence and provoked a

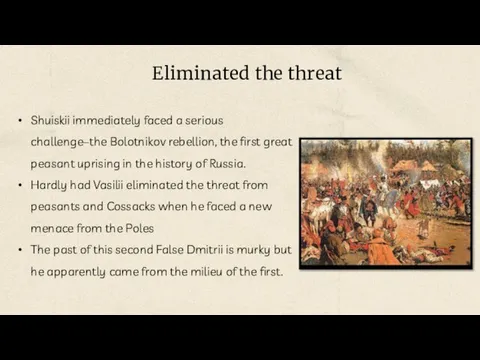

- 9. Shuiskii immediately faced a serious challenge–the Bolotnikov rebellion, the first great peasant uprising in the history

- 10. After establishing headquarters in the village of Tushino, he was joined by the wife of the

- 11. Thus, for the first time in Russian history, élites set terms for accession to the throne.

- 12. The tensions were soon apparent in Moscow, where the high‑handed behaviour of the Poles and their

- 13. The ‘third levy’, though beset with internal differences, nevertheless liberated Moscow in October 1612. The liberation

- 15. Скачать презентацию

Слайд 2Project Plan

Introduction

01

The ‘Times of Troubles’

First Phase

02

End of Rurik dyansty

2nd Phase

03

‘Social Crisis’

3rd

Project Plan

Introduction

01

The ‘Times of Troubles’

First Phase

02

End of Rurik dyansty

2nd Phase

03

‘Social Crisis’

3rd

04

05

Questions

‘National Crisis’

Слайд 3The age of transformation began with acute crisis–the ‘Time of Troubles’ (smutnoe

The age of transformation began with acute crisis–the ‘Time of Troubles’ (smutnoe

This period divides into successive ‘dynastic’, ‘social’, and ‘national’ phases that followed upon one another.

The ‘Dynastic period’ or ‘First phase’ begins with the extinction of the Riurik line in 1598.

This first phase was unusual because the only dynasty that had ever reigned in Russia suddenly vanished without issue, and due to this it triggered the first assault on the autocracy.

In the broadest sense, the old order lost a principal pillar–tradition (starina); nevertheless, there remained the spiritual support of the Orthodox Church and the service nobility.

Muscovy responded to the extinction of its ruling dynasty by electing a new sovereign. Boris Godunov– a Russian nobleman but he was not from an élite family.

The ‘Time of Troubles’ (smutnoe vremia).

Слайд 4

But Boris had prepared his development under Tsars Ivan the Terrible and

But Boris had prepared his development under Tsars Ivan the Terrible and

After Fedor’s death, Boris was formally ‘elected’ as Tsar Boris by a council (sobor) who had gathered in Moscow. The Church, which Boris had earlier helped to establish its own Patriarchate, supported his election.

Boris’s position was secure. Apart from fact that his government was surround with enormous burdens and problems, Boris himself failed to invoke respect from his subjects.

Moreover, his open efforts to ascend the throne give belief to rumours that he had arranged the murder of Tsarevich Dmitrii, Ivan’s last son, in 1591. Although an investigation confirmed that the death was accidental.

Boris Godunov– As A Ruler

Слайд 5Boris was unable to consolidate power after accession to the throne.

His attempt

Boris was unable to consolidate power after accession to the throne.

His attempt

He was also not able to train better state servants: when, for the 1st time, Muscovy dispatched 18 men to study in England, France, and Germany, not a single one returned.

Boris attempted to establish order in noble‑peasant relations, but nature herself interceded. From the early 1590s, in an attempt to protect petty nobles and to promote economic recovery, the government established the ‘forbidden years’, which–for the 1st time–imposed a blanket prohibition on peasant movement during the stipulated year.

Fall Of Boris Empire

Слайд 6In autumn 1601, however, Boris’s government had to retreat and reaffirm the

In autumn 1601, however, Boris’s government had to retreat and reaffirm the

The following year the government again had to rescind the ‘forbidden year’, a step that virtually legalized massive peasant flight.

Moreover the government welcomed movement towards the southern border area (appropriately called the dikoe pole, or ‘wild field’), where they helped to reinforce the Cossacks and the fortified towns recently established as a buffer between Muscovy and the Crimean Tatars.

But many peasants sought new landowners in central Muscovy adding to the social unrest. In fact, in 1603 the government had to use troops to suppress rebellious peasants, bondsmen (kholopy ), and even déclassé petty nobles.

End of The First Phase

Слайд 7The general sense of catastrophe mounted, rumours suddenly spread that Tsarevich Dmitrii

The general sense of catastrophe mounted, rumours suddenly spread that Tsarevich Dmitrii

When the Polish nobles launched their campaign from Lvov in August 1604, their forces numbered only 2,200 cavalrymen.

By the time they entered the Kremlin, Boris himself had already died (April 1605), and his 16‑year‑old son Fedor was promptly executed.

Death of Tsarevich Dmitrii and Boris

Слайд 8Above all, the Polish presence exposed old Russian culture to massive Western

Above all, the Polish presence exposed old Russian culture to massive Western

It is hardly surprising that Shuiskii himself mounted the throne–this time ‘chosen’ by fellow boyars, not a council of the realm.

Alexander Nevsky he represented the hope of aristocratic lines pushed into the background by Boris and Dmitrii.

Shuiskii and Russian culture

Слайд 9Shuiskii immediately faced a serious challenge–the Bolotnikov rebellion, the first great peasant

Shuiskii immediately faced a serious challenge–the Bolotnikov rebellion, the first great peasant

Hardly had Vasilii eliminated the threat from peasants and Cossacks when he faced a new menace from the Poles

The past of this second False Dmitrii is murky but he apparently came from the milieu of the first.

Eliminated the threat

Слайд 10After establishing headquarters in the village of Tushino, he was joined by

After establishing headquarters in the village of Tushino, he was joined by

After some initial tensions, Moscow and Sweden soon enjoyed military success, overrunning the camp at Tushino at the end of 1609; a few months later the Swedish troops marched into Moscow.

As Vasilii’s power waned, in February 1610 his foes struck a deal with the king of Poland: his son Władysław, successor to the Polish throne, would become tsar on condition that he promise to uphold Orthodoxy and to allow the election of a monarch in accordance with Polish customs.

Military success

Слайд 11Thus, for the first time in Russian history, élites set terms for

Thus, for the first time in Russian history, élites set terms for

The agreement provided for a council of seven boyars (legitimized by an ad hoc council of the realm), which, with a changing composition, sought to govern during the interregnum.

That Muscovy obtained neither a Polish tsar nor a limited monarchy in 1610 was due to a surprising turn of events in Smolensk.

Agreement of 7 boyars

Слайд 12The tensions were soon apparent in Moscow, where the high‑handed behaviour of

The tensions were soon apparent in Moscow, where the high‑handed behaviour of

In response Nizhnii Novgorod and Vologda raised the ‘second levy’, which united with the former supporters of the second False Dmitrii and advanced on Moscow.

The supreme council of his army functioned as a government (for example, assessing taxes), but avoided any promise of freedom for fugitive peasants once the strife had ended.

Second Levy

Слайд 13The ‘third levy’, though beset with internal differences, nevertheless liberated Moscow in

The ‘third levy’, though beset with internal differences, nevertheless liberated Moscow in

The liberation of Moscow did not mean an end to the turbulent ‘Time of Troubles’: for years to come, large parts of the realm remained under Swedish and Polish occupation.

And, despite the election of a new tsar, society became more self‑conscious as it entered upon decades of tumult in the ‘rebellious century’.

Liberation of Moscow

Память и памятники

Память и памятники Тачки. Двадцатые

Тачки. Двадцатые Гражданская война в Соединённых Штатах Америки - вторая буржуазная революция

Гражданская война в Соединённых Штатах Америки - вторая буржуазная революция Предметная неделя по истории 13 декабря-19 декабря 2021 г

Предметная неделя по истории 13 декабря-19 декабря 2021 г Национальные герои Англии

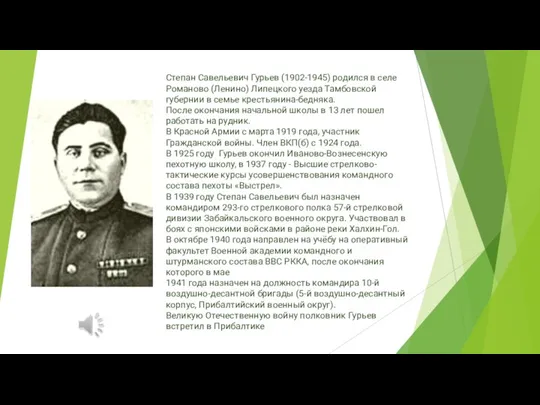

Национальные герои Англии Степан Савельевич Гурьев (1902-1945)

Степан Савельевич Гурьев (1902-1945) Развитие образования во второй половине XIIX века

Развитие образования во второй половине XIIX века Историко-культурного центра Берег памяти

Историко-культурного центра Берег памяти English monarchs' nicknames

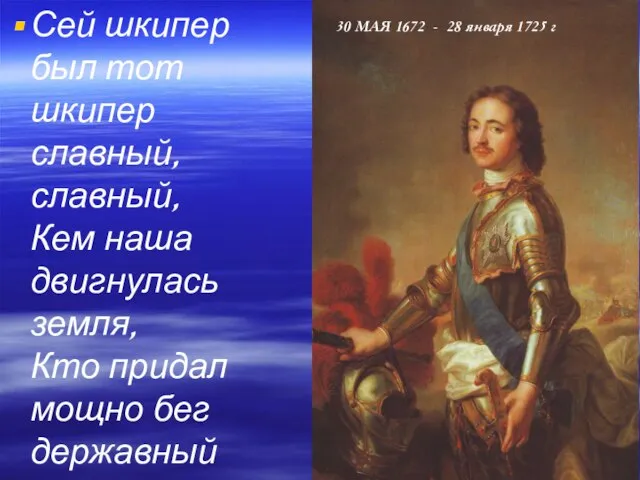

English monarchs' nicknames Сей шкипер был тот шкипер славный, славный, Кем наша двигнулась земля, Кто придал мощно бег державный Рулю родного корабля! Сей шки

Сей шкипер был тот шкипер славный, славный, Кем наша двигнулась земля, Кто придал мощно бег державный Рулю родного корабля! Сей шки Храмовые и дворцовые комплексы как градообразующие центры Древнего мира

Храмовые и дворцовые комплексы как градообразующие центры Древнего мира Балкып яшә, Татарстан!

Балкып яшә, Татарстан! История народов Восточной Европы

История народов Восточной Европы Образ Салавата Юлаева в картинах художников Башкортостана

Образ Салавата Юлаева в картинах художников Башкортостана Савельев М. И

Савельев М. И Понятие об обособлении

Понятие об обособлении Кронштадтское восстание

Кронштадтское восстание Путешествие в прошлое книги

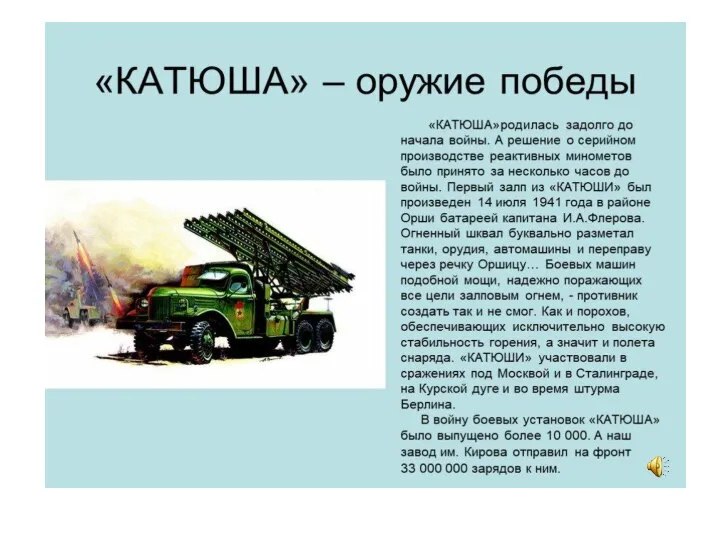

Путешествие в прошлое книги Катюша - орудие победы

Катюша - орудие победы Путешествие по Свердловской области

Путешествие по Свердловской области sssr_v_1964-1982_gg._brezhnev

sssr_v_1964-1982_gg._brezhnev Юнармейский отряд Соколята России. Я помню! Я горжусь!

Юнармейский отряд Соколята России. Я помню! Я горжусь! Холодная война

Холодная война Маленькие герои Великой Отечественной войны

Маленькие герои Великой Отечественной войны Жилище славян

Жилище славян Презентация на тему Строительство новой Федерации

Презентация на тему Строительство новой Федерации  Великая Отечественная война (1941-1945)

Великая Отечественная война (1941-1945) Государство Востока в XVI-XVII Япония

Государство Востока в XVI-XVII Япония