Содержание

- 2. There’s no more iconic symbol of medieval Europe than the knight: clad in shining armor, jousting

- 3. Naturally, as leaders of armies, knights were responsible for winning—and losing—some of the most important battles

- 4. William of Poitiers One of the earliest and most significant victories for knights in the Middle

- 5. Hugues de Payens As the co-founder and first Grand Master of the Knights Templar, Hugues de

- 6. William Marshal The fourth son of a minor noble, William Marshal (c 1146 –1219) rose to

- 7. Edward the Black Prince Edward of Woodstock (1330-1376), who became known as the Black Prince, was

- 9. Скачать презентацию

Слайд 2There’s no more iconic symbol of medieval Europe than the knight: clad

There’s no more iconic symbol of medieval Europe than the knight: clad

in shining armor, jousting with his rivals, wearing a token of his lady love. But knights were far more than romantic figures—they were a triumph of military technology. Accounts from the Middle Ages describe the well-trained, heavily-armed warriors trampling through enemy forces while chopping off limbs and heads.

The resources needed for horses, armor and weaponry meant that knighthood was generally a job for the rich. Most knights came from noble families, and success in battle might lead to a royal grant of additional land and titles.

The resources needed for horses, armor and weaponry meant that knighthood was generally a job for the rich. Most knights came from noble families, and success in battle might lead to a royal grant of additional land and titles.

Слайд 3Naturally, as leaders of armies, knights were responsible for winning—and losing—some of

Naturally, as leaders of armies, knights were responsible for winning—and losing—some of

the most important battles of the Middle Ages. But they also made history in other ways. Many held important religious positions as well as military ones. Some were writers of history and poetry, helping to craft the image of the knight that we still know today.

Слайд 4William of Poitiers

One of the earliest and most significant victories for knights

William of Poitiers

One of the earliest and most significant victories for knights

in the Middle Ages was the Norman conquest of England, and a lot of what we know about that fight comes from William of Poitiers (c. 1020 – 1090). Trained as a knight in his youth, William went on to become a priest and scholar. When William the Conqueror invaded England in 1066, William of Poitiers was his chaplain. Later, he provided a well-known account of the king’s life and the conquest.

The priest didn’t hesitate to flatter his king in his writing, describing his charge into battle with gleaming shield and lance as “a sight both delightful and terrible to see.” But, despite his biases, William of Poitiers worked hard to get his facts right. For example, his account of the Battle of Hastings—a triumph of mounted knights against an Anglo-Saxon army made up mostly of infantry—is based largely on eyewitness accounts from soldiers who fought there, providing one of the most important sources for modern historians.

The priest didn’t hesitate to flatter his king in his writing, describing his charge into battle with gleaming shield and lance as “a sight both delightful and terrible to see.” But, despite his biases, William of Poitiers worked hard to get his facts right. For example, his account of the Battle of Hastings—a triumph of mounted knights against an Anglo-Saxon army made up mostly of infantry—is based largely on eyewitness accounts from soldiers who fought there, providing one of the most important sources for modern historians.

Слайд 5Hugues de Payens

As the co-founder and first Grand Master of the

Hugues de Payens

As the co-founder and first Grand Master of the

Knights Templar, Hugues de Payens (c. 1070 – 1136) was a key figure in this history of the Crusades. Historical details of his early life are sketchy, but the French nobleman may have fought in the First Crusade, in which European Christian armies captured Jerusalem.

As Christians increasingly took part in pilgrimages to the holy city, they often found themselves under attack on the road. And so, around 1118, de Payens and eight fellow knights sought permission from Jerusalem’s king, Baldwin II, to form a protective service for the pilgrims. The Knights Templar earned support from Christian authorities, including Pope Innocent II, who in 1139 granted them exemption from taxes and from any authority except his own.

The Knights Templar grew into a major economic force, with a network of banks, a fleet of ships, and chapters all over Europe. But, when Muslims retook Jerusalem in the late 12th century, the order lost its place there. More than a century later, King Philip IV of France dealt the Knights its death blow, having many of its members tortured and killed and finally executing its last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, in 1307.

As Christians increasingly took part in pilgrimages to the holy city, they often found themselves under attack on the road. And so, around 1118, de Payens and eight fellow knights sought permission from Jerusalem’s king, Baldwin II, to form a protective service for the pilgrims. The Knights Templar earned support from Christian authorities, including Pope Innocent II, who in 1139 granted them exemption from taxes and from any authority except his own.

The Knights Templar grew into a major economic force, with a network of banks, a fleet of ships, and chapters all over Europe. But, when Muslims retook Jerusalem in the late 12th century, the order lost its place there. More than a century later, King Philip IV of France dealt the Knights its death blow, having many of its members tortured and killed and finally executing its last Grand Master, Jacques de Molay, in 1307.

Слайд 6William Marshal

The fourth son of a minor noble, William Marshal (c

William Marshal

The fourth son of a minor noble, William Marshal (c

1146 –1219) rose to become one of the most admired knights in English history. In his early years as a knight, he fought in tournaments where hundreds or even thousands of fighters would engage in melee-style mock battles. He rose to stardom traveling from tournament to tournament, and got rich on the prizes he won.

He went on to serve five English kings, and to marry the heiress Isabel de Clare, becoming one of the richest men in the country. William helped in the negotiations between King John and his Barons that led to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215. When King John died in 1216, making nine-year-old Henry III king, William became Regent of England. Although he was about 70 by then, he led the young king’s army to victory over French forces and rebellious barons the following year.

He went on to serve five English kings, and to marry the heiress Isabel de Clare, becoming one of the richest men in the country. William helped in the negotiations between King John and his Barons that led to the signing of the Magna Carta in 1215. When King John died in 1216, making nine-year-old Henry III king, William became Regent of England. Although he was about 70 by then, he led the young king’s army to victory over French forces and rebellious barons the following year.

Слайд 7Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (1330-1376), who became known as

Edward the Black Prince

Edward of Woodstock (1330-1376), who became known as

the Black Prince, was one of the most famous commanders during the Hundred Years’ War. He was the son and heir apparent of Edward III of England and served in his first military campaigns in northern France at about age 16. He became a commander in the war less than a decade later. His most famous campaign was the Battle of Poitiers in 1356, where he captured King John II of France. In accordance with chivalric conventions, he treated the king with great courtesy but, before releasing him, demanded a true king’s random of 3 million gold crowns, as well as treaties that granted England territory in what is now western France.

Edward was known for his knightly—and wealthy—lifestyle, enjoying jousting, falconry, and hunting, and providing charity to religious causes.

Edward was known for his knightly—and wealthy—lifestyle, enjoying jousting, falconry, and hunting, and providing charity to religious causes.

- Предыдущая

Кожа – индикатор здоровья 260-летию села посвящается

260-летию села посвящается Я помню - я горжусь

Я помню - я горжусь Российские сословия

Российские сословия Город Сольвычегодск

Город Сольвычегодск Политико-правовая мысль средних веков

Политико-правовая мысль средних веков Русь расправляет крылья. Тест Трудные времена на Руси

Русь расправляет крылья. Тест Трудные времена на Руси Новая Россия. Итоги реформ

Новая Россия. Итоги реформ Путешествие в прошлое бумаги

Путешествие в прошлое бумаги Ветеранам ВОВ от детей старшей группы отд. № 2

Ветеранам ВОВ от детей старшей группы отд. № 2 Борьба Руси с западными завоевателями

Борьба Руси с западными завоевателями Виникнення архівів в часи Середньовіччя

Виникнення архівів в часи Середньовіччя Российская наука первой половины XIX века

Российская наука первой половины XIX века Актуальность геополитики. Мировое геополитическое пространство

Актуальность геополитики. Мировое геополитическое пространство Kushtau. Xistory of conflict

Kushtau. Xistory of conflict Память о героях нетленна

Память о героях нетленна Художественная культура России 18 века

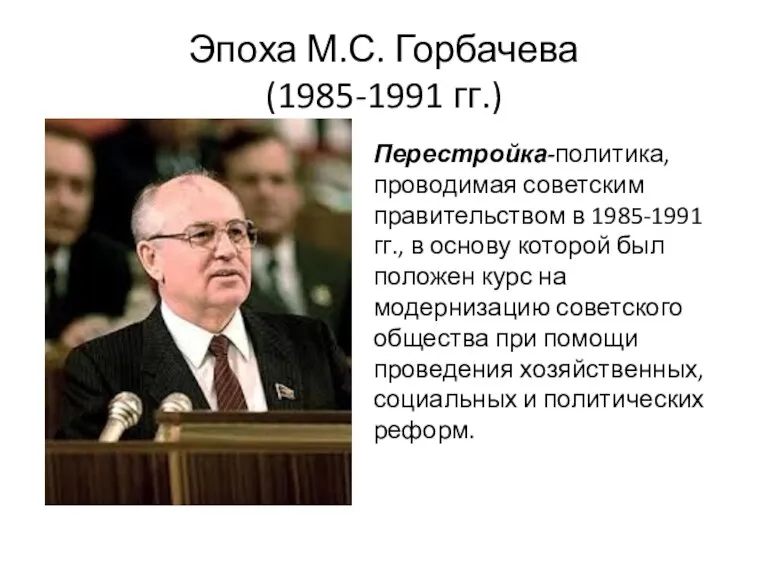

Художественная культура России 18 века Эпоха М.С. Горбачева (1985-1991 гг.)

Эпоха М.С. Горбачева (1985-1991 гг.) Археология. Труд археолога

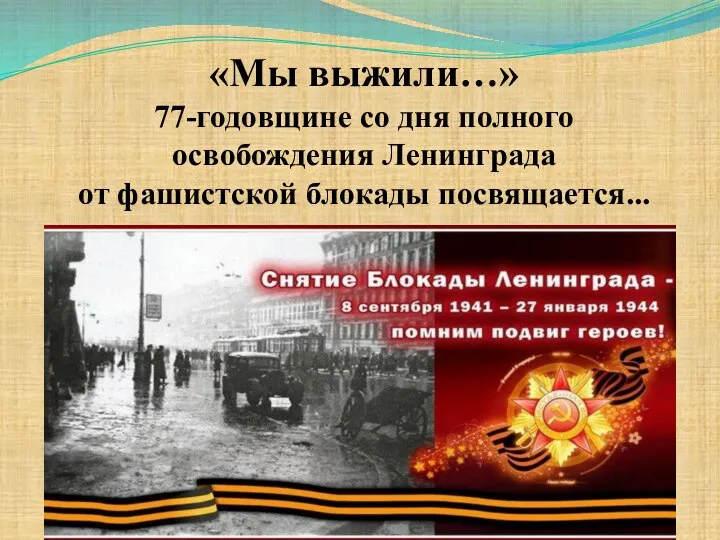

Археология. Труд археолога Мы выжили… 77-годовщине со дня полного освобождения Ленинграда от фашистской блокады посвящается

Мы выжили… 77-годовщине со дня полного освобождения Ленинграда от фашистской блокады посвящается Термидорианская республика

Термидорианская республика Восстановление народного хозяйства и экономики в послевоенный период. Культурное и политическое восстановление

Восстановление народного хозяйства и экономики в послевоенный период. Культурное и политическое восстановление Презентация на тему Киевская Русь при Владимире Святославовиче

Презентация на тему Киевская Русь при Владимире Святославовиче  От первобытности к цивилизации

От первобытности к цивилизации Памятные места Забайкальского края. Квест

Памятные места Забайкальского края. Квест Массовая культура 1990-2000 годов

Массовая культура 1990-2000 годов Война за Независимость в Северной Америке (1775-1783) и образование США

Война за Независимость в Северной Америке (1775-1783) и образование США Вхождение Крыма и Севастополя в состав РФ

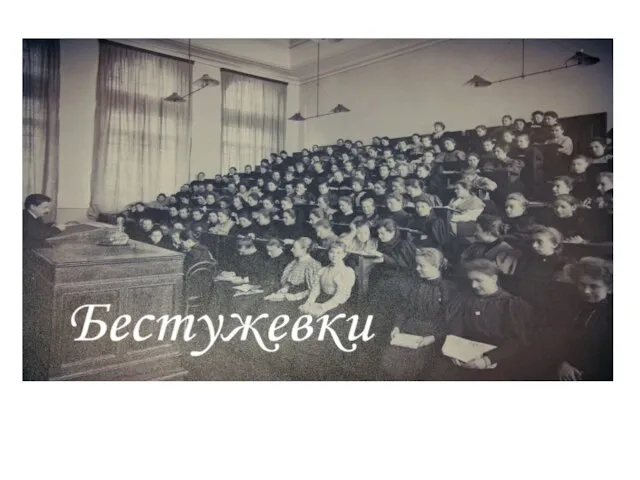

Вхождение Крыма и Севастополя в состав РФ Бестужевки. 140 лет первому в России высшему учебному заведению для женщин

Бестужевки. 140 лет первому в России высшему учебному заведению для женщин