Содержание

- 2. Nikola Tesla: Wizard of the Industrial Revolution

- 3. Nikola Tesla grips his hat in his hand. He points his cane toward Niagara Falls and

- 4. Tesla is perhaps best known for his eccentric genius. He once proposed a system of towers

- 5. While his work was truly genius, much of his wizardly reputation was of his own making.

- 6. Carl Linnaeus: Say His Name(s)

- 7. It started in Sweden: a functional, user-friendly innovation that took over the world, bringing order to

- 8. The 18th century was also a time when European explorers were fanning out across the globe,

- 9. Today we regard Linnaeus as the father of taxonomy, which is used to sort the entire

- 11. Скачать презентацию

Слайд 3Nikola Tesla grips his hat in his hand. He points his cane

Nikola Tesla grips his hat in his hand. He points his cane

toward Niagara Falls and beckons bystanders to turn their gaze to the future. This bronze Tesla — a statue on the Canadian side — stands atop an induction motor, the type of engine that drove the first hydroelectric power plant.

We owe much of our modern electrified life to the lab experiments of the Serbian-American engineer, born in 1856 in what’s now Croatia. His designs advanced alternating current at the start of the electric age and allowed utilities to send current over vast distances, powering American homes across the country. He developed the Tesla coil — a high-voltage transformer — and techniques to transmit power wirelessly. Cellphone makers (and others) are just now utilizing the potential of this idea.

We owe much of our modern electrified life to the lab experiments of the Serbian-American engineer, born in 1856 in what’s now Croatia. His designs advanced alternating current at the start of the electric age and allowed utilities to send current over vast distances, powering American homes across the country. He developed the Tesla coil — a high-voltage transformer — and techniques to transmit power wirelessly. Cellphone makers (and others) are just now utilizing the potential of this idea.

Слайд 4Tesla is perhaps best known for his eccentric genius. He once proposed

Tesla is perhaps best known for his eccentric genius. He once proposed

a system of towers that he believed could pull energy from the environment and transmit signals and electricity around the world, wirelessly. But his theories were unsound, and the project was never completed. He also claimed he had invented a “death ray.”

In recent years, Tesla’s mystique has begun to eclipse his inventions. San Diego Comic-Con attendees dress in Tesla costumes. The world’s most famous electric car bears his name. The American Physical Society even has a Tesla comic book (where, as in real life, he faces off against the dastardly Thomas Edison).

In recent years, Tesla’s mystique has begun to eclipse his inventions. San Diego Comic-Con attendees dress in Tesla costumes. The world’s most famous electric car bears his name. The American Physical Society even has a Tesla comic book (where, as in real life, he faces off against the dastardly Thomas Edison).

Слайд 5While his work was truly genius, much of his wizardly reputation was

While his work was truly genius, much of his wizardly reputation was

of his own making. Tesla claimed to have accidentally caused an earthquake in New York City using a small steam-powered electric generator he’d invented — MythBustersdebunked that idea. And Tesla didn’t actually discover alternating current, as everyone thinks. It was around for decades. But his ceaseless theories, inventions and patents made Tesla a household name, rare for scientists a century ago. And even today, his legacy still turns the lights on. — Eric Betz

Слайд 6Carl Linnaeus: Say His Name(s)

Carl Linnaeus: Say His Name(s)

Слайд 7It started in Sweden: a functional, user-friendly innovation that took over the

It started in Sweden: a functional, user-friendly innovation that took over the

world, bringing order to chaos. No, not an Ikea closet organizer. We’re talking about the binomial nomenclature system, which has given us clarity and a common language, devised by Carl Linnaeus.

Linnaeus, born in southern Sweden in 1707, was an “intensely practical” man, according to Sandra Knapp, a botanist and taxonomist at the Natural History Museum in London. He lived at a time when formal scientific training was scant and there was no system for referring to living things. Plants and animals had common names, which varied from one location and language to the next, and scientific “phrase names,” cumbersome Latin descriptions that could run several paragraphs.

Linnaeus, born in southern Sweden in 1707, was an “intensely practical” man, according to Sandra Knapp, a botanist and taxonomist at the Natural History Museum in London. He lived at a time when formal scientific training was scant and there was no system for referring to living things. Plants and animals had common names, which varied from one location and language to the next, and scientific “phrase names,” cumbersome Latin descriptions that could run several paragraphs.

Слайд 8The 18th century was also a time when European explorers were fanning

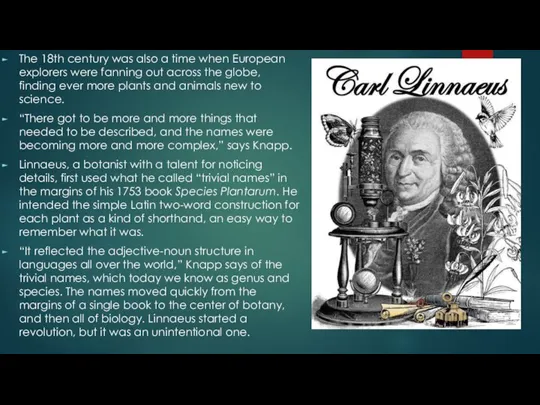

The 18th century was also a time when European explorers were fanning

out across the globe, finding ever more plants and animals new to science.

“There got to be more and more things that needed to be described, and the names were becoming more and more complex,” says Knapp.

Linnaeus, a botanist with a talent for noticing details, first used what he called “trivial names” in the margins of his 1753 book Species Plantarum. He intended the simple Latin two-word construction for each plant as a kind of shorthand, an easy way to remember what it was.

“It reflected the adjective-noun structure in languages all over the world,” Knapp says of the trivial names, which today we know as genus and species. The names moved quickly from the margins of a single book to the center of botany, and then all of biology. Linnaeus started a revolution, but it was an unintentional one.

“There got to be more and more things that needed to be described, and the names were becoming more and more complex,” says Knapp.

Linnaeus, a botanist with a talent for noticing details, first used what he called “trivial names” in the margins of his 1753 book Species Plantarum. He intended the simple Latin two-word construction for each plant as a kind of shorthand, an easy way to remember what it was.

“It reflected the adjective-noun structure in languages all over the world,” Knapp says of the trivial names, which today we know as genus and species. The names moved quickly from the margins of a single book to the center of botany, and then all of biology. Linnaeus started a revolution, but it was an unintentional one.

Слайд 9Today we regard Linnaeus as the father of taxonomy, which is used

Today we regard Linnaeus as the father of taxonomy, which is used

to sort the entire living world into evolutionary hierarchies, or family trees. But the systematic Swede was mostly interested in naming things rather than ordering them, an emphasis that arrived the next century with Charles Darwin.

As evolution became better understood and, more recently, genetic analysis changed how we classify and organize living things, many of Linnaeus’ other ideas have been supplanted. But his naming system, so simple and adaptable, remains.

“It doesn’t matter to the tree in the forest if it has a name,” Knapp says. “But by giving it a name, we can discuss it. Linnaeus gave us a system so we could talk about the natural world.” — Gemma Tarlach

As evolution became better understood and, more recently, genetic analysis changed how we classify and organize living things, many of Linnaeus’ other ideas have been supplanted. But his naming system, so simple and adaptable, remains.

“It doesn’t matter to the tree in the forest if it has a name,” Knapp says. “But by giving it a name, we can discuss it. Linnaeus gave us a system so we could talk about the natural world.” — Gemma Tarlach

- Предыдущая

Устная речевая презентацияСледующая -

ЖК Фрукты для клиентов

Усиление королевской власти в конце XV в. во Франции и Англии

Усиление королевской власти в конце XV в. во Франции и Англии Коллективизация сельского хозяйства

Коллективизация сельского хозяйства Память о Холокосте –путь к толерантности

Память о Холокосте –путь к толерантности Происхождение человека

Происхождение человека Пуритане в Англии

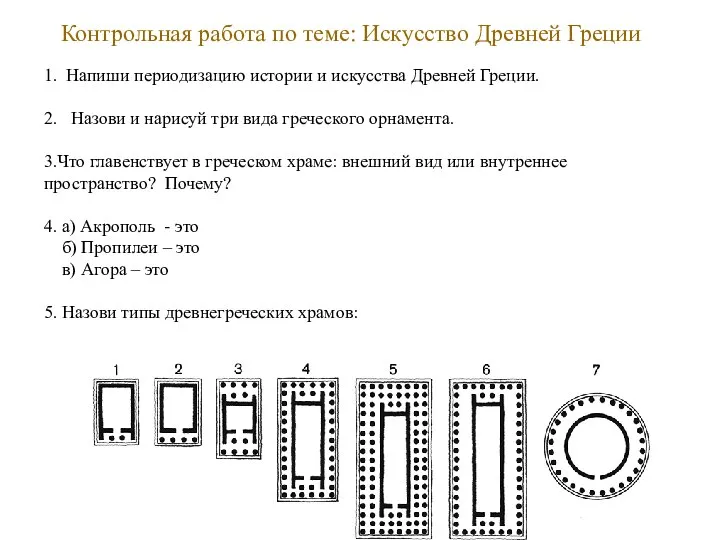

Пуритане в Англии Контрольный урок по искусству Древней Греции

Контрольный урок по искусству Древней Греции Источники древнеримского права

Источники древнеримского права Петровская эпоха (1682(1696)-1725), 10 класс

Петровская эпоха (1682(1696)-1725), 10 класс 3 декабря - День Неизвестного солдата

3 декабря - День Неизвестного солдата СССР и союзники в годы Второй мировой войны

СССР и союзники в годы Второй мировой войны Презентация на тему "Культура СССР" - презентации по Истории

Презентация на тему "Культура СССР" - презентации по Истории  Вакилов Билал Садретдинович

Вакилов Билал Садретдинович Сыновья земли русской

Сыновья земли русской Экскурсионная деятельность Путешествуя по Уральским святыням

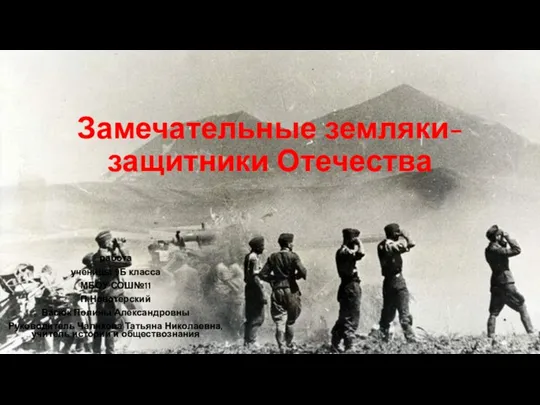

Экскурсионная деятельность Путешествуя по Уральским святыням Замечательные земляки — защитники Отечества. п.Новотерский

Замечательные земляки — защитники Отечества. п.Новотерский С чего начинается Родина

С чего начинается Родина Улица Героев Панфиловцев

Улица Героев Панфиловцев Родиновединье. Пешая слобода

Родиновединье. Пешая слобода стр.79

стр.79 7bec653956c64fc1917556f970506a29

7bec653956c64fc1917556f970506a29 Развитие медицины с момента правления В.В. Путина

Развитие медицины с момента правления В.В. Путина Появление трамвая

Появление трамвая История государственных наград России и Советского союза, выдававшихся за военные заслуги перед Отечеством

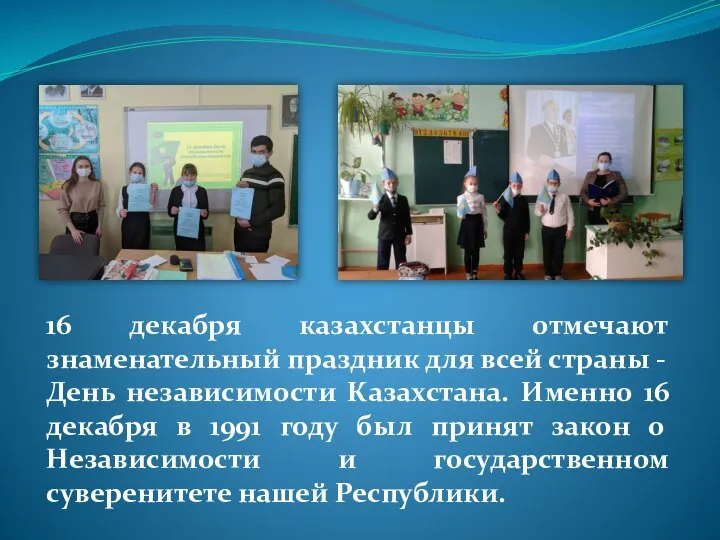

История государственных наград России и Советского союза, выдававшихся за военные заслуги перед Отечеством День независимости Казахстана

День независимости Казахстана Мир после Первой Мировой войны

Мир после Первой Мировой войны История развития советско-германских отношений в 20-30-е гг. ХХв

История развития советско-германских отношений в 20-30-е гг. ХХв Достопримечательности Акбулака

Достопримечательности Акбулака Археография

Археография