Слайд 21. Is free trade anti-environment

Free trade will change the composition of production

and consumption in each country. As the composition changes, the total amounts of pollution will change.

There are gains from trade, which set up two different effects

The size of the economy is larger, which implies more pollution, ceteris paribus

The higher income can lead to more pressure on governments to enact tougher environmental laws

Слайд 3Is free trade anti environment

Which effect is larger: harm from the size

or the environmental protection from the income effect?

There are three basic patterns depending on the environmental problem we are examining:

Environmental harm declines with rising income per person (i.e. lead)

Environmental harm rises with rising income per person (i.e. emissions of carbon dioxide)

The relationship is an inverted U (i.e. air pollution and water pollution)

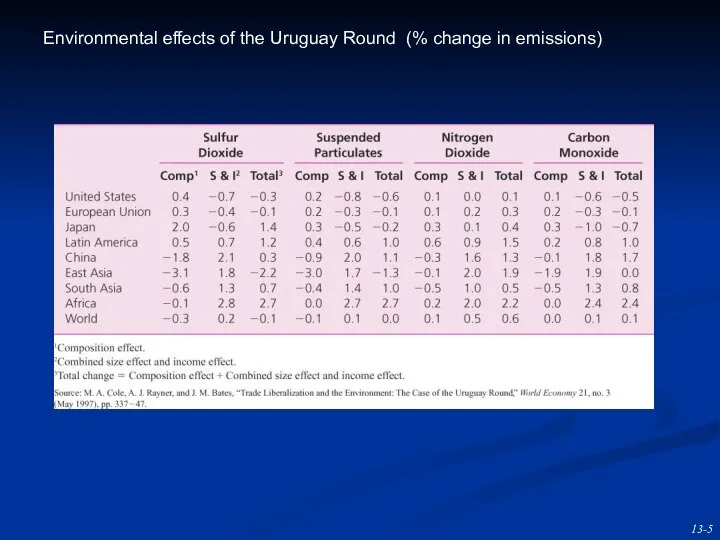

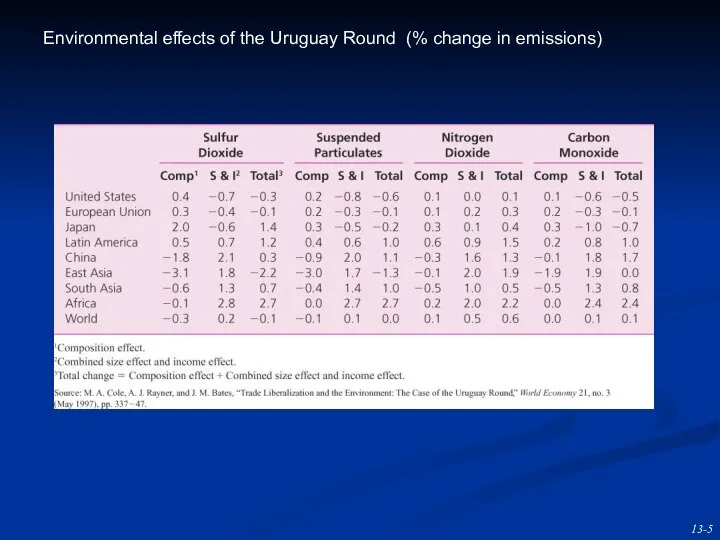

Слайд 5Environmental effects of the Uruguay Round (% change in emissions)

Слайд 62. Specificity rule again

An externality leads to an inefficient allocation of resources,

and there is a role for government intervention in the market

The specificity rule is a useful policy guide

The specificity rules says to intervene at the source of the problem

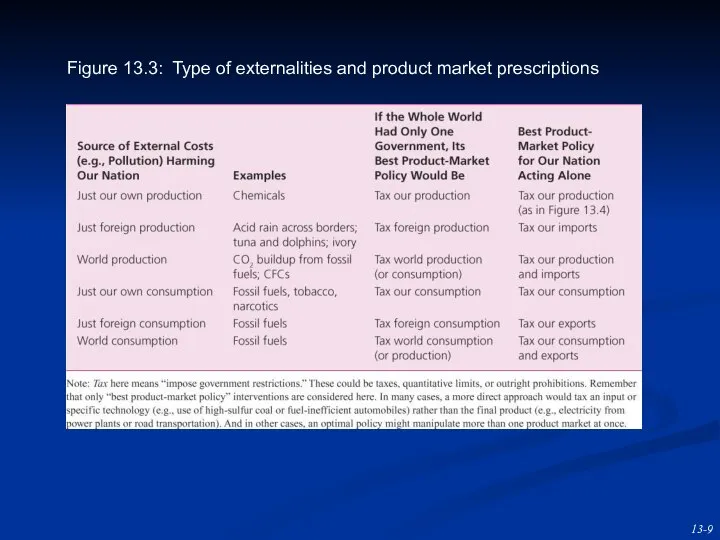

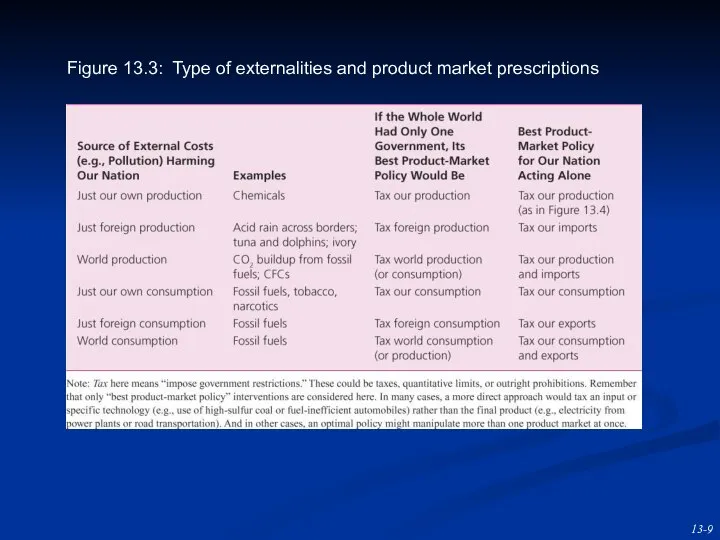

Слайд 73. Guidelines for policy prescriptions

Following the specificity rule, if the externality is

pollution, make pollution itself more expensive.

See Figure 13.3

The figure contains two sets of best-feasible prescriptions:

The whole world acting as one government

A single nation unable to get cooperation from other governments

Слайд 83. Guidelines for policy prescriptions

If the world acts as one government there

is no need for international trade policy (i.e. taxes on exports and imports): taxes are on production and consumption.

According to the specificity rule, taxes are near the source of the pollution.

If a nation must act alone, then trade barriers could be an appropriate solution.

Слайд 9Figure 13.3: Type of externalities and product market prescriptions

Слайд 104. Trade and domestic pollution

Domestic pollution occurs when the costs of pollution

fall (almost) only on people within the country

In this case, in the absence of any regulation:

Free trade can reduce the well-being of the country

the country can end up exporting the products that it should import

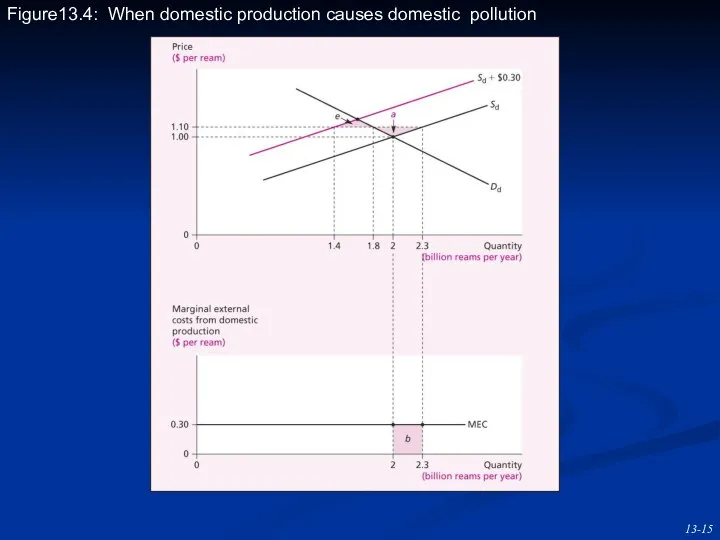

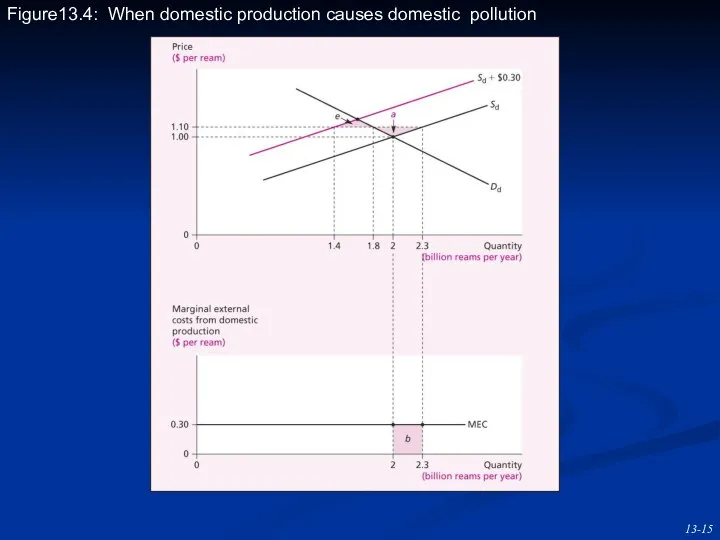

See Figure 13.4

Слайд 114. Trade and domestic pollution

The top half of the figure shows:

Domestic supply

curve (private MC of paper production)

Domestic demand curve (private MB of paper consumption)

The bottom half of the figure shows the cost of pollution or marginal external cost (MEC) of producing paper.

Marginal Social Cost (MSC)= Private MC+MEC

Слайд 124. Trade and domestic pollution

With no international trade, the paper market clears

at P=$1 per ream and Q=2 billion reams.

With no recognition of pollution costs, this is an over production of paper

Under free trade, the price rises to $1.10, domestic production rises to 2.3 billion, domestic consumption falls to 1.8 billion (a fall of 0.5 billion)

The free trade makes the country worse off: area a < area b (or the gain from trade is less than the cost of pollution)

Слайд 134. Trade and domestic pollution

The government could impose a tax to tackle

the pollution problem

The tax should equal the marginal external cost of production (t=MEC)

The domestic supply curve shifts up by the amount of the tax. Now the new supply curve reflects all social costs (SMC=Sd+0.30).

Слайд 144. Trade and domestic pollution

If there is this a tax

Domestic demand=1.8 billion

Domestic

production=1.4 billion

The country should import (M=0.4 billion) rather than export paper

The gain from trade is represented by the triangle e

With no government policy limiting pollution:

The country can end up worse off with free trade

The trade pattern can be wrong

Слайд 15Figure13.4: When domestic production causes domestic pollution

Слайд 16Trans-border pollution

Many types of pollution have transborder effects (i.e. air pollution, sulphur

dioxide drifts across national borders)

It raises major issues for governments policy

Suppose there are two countries: Germany and Austria

Suppose a German paper company builds a new paper mill on the Danube and dumps chemical waste into the river

The river flows into Austria and imposes external costs on Austrians

Слайд 17Trans-border pollution

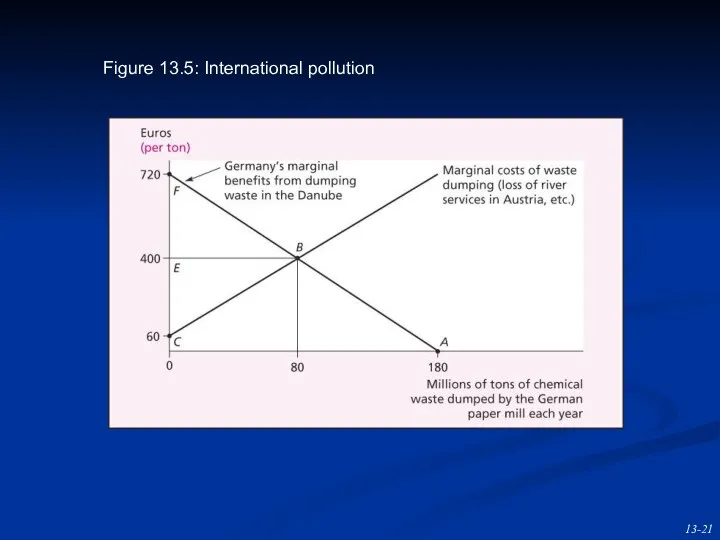

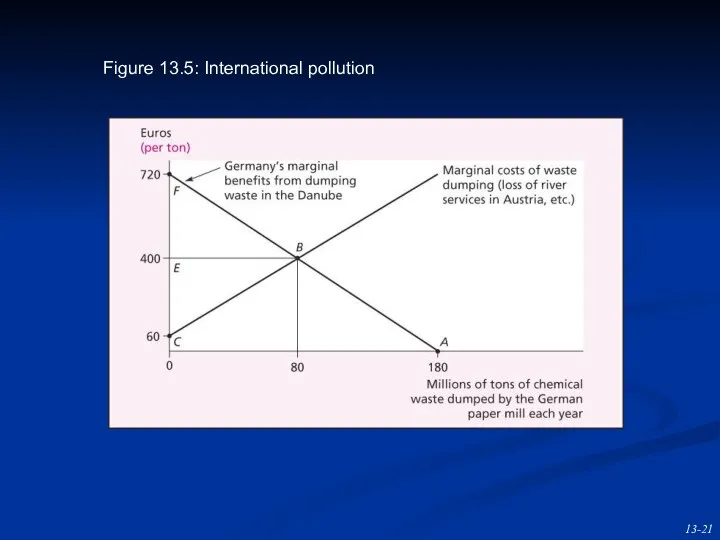

How do we determine the optimum amount of pollution? (See Figure

13.5)

The figure shows the Germany’s benefits and Austria’s costs from different rates of dumping waste into the river by the paper mill.

In a free market with no government intervention, the firm will pollute until benefits are equal to zero (point A).

This imposes a large costs on Austrians along the MC curve.

Слайд 18Trans-border pollution

Point A is also inefficient from a world perspective: MBBut a

total ban on river pollution is inefficient as well. At zero pollution MB>MC.

The efficient level of pollution is 80 tons per year, where MB=MC

Слайд 19Trans-border pollution

A tax will not work in this situation because of the

trans-border nature of the pollution

Austria has no direct taxing power over a paper mill in Germany

Germany might not tax the paper mill at all

International negotiations between the two countries is required to achieve the efficient outcome

Слайд 20Trans-border pollution

If they fail, the Austrian government could attempt to reduce imports

from Germany

This could reduce pollution in the river if Austria is a major importer of paper from Germany

Problem: WTO rules prohibit import tariffs such as this

Слайд 21Figure 13.5: International pollution

Слайд 23Global environmental challenges

Extinction of species

Overfishing

CFCs and the Ozone Layer

Greenhouse gasses and global

Warming

Kyoto Protocol

Copenhagen accord

A global approach

Macroeconomics

Macroeconomics Экономический рост и его типы

Экономический рост и его типы Экономические функции домохозяйства. 10 класс

Экономические функции домохозяйства. 10 класс Хозяйство и экономика страны

Хозяйство и экономика страны Завершение проекта

Завершение проекта Прямое государственное воздействие на цены и ценообразование

Прямое государственное воздействие на цены и ценообразование Бюджетная система Российской Федерации. Электронные учебные издания

Бюджетная система Российской Федерации. Электронные учебные издания Особенности регулирования ВЭД в Словакии

Особенности регулирования ВЭД в Словакии Национальное счетоводство

Национальное счетоводство Фиаско рынка

Фиаско рынка Организация производства на предприятии

Организация производства на предприятии О разработке проектно-сметной документации по детскому саду и школе в г. Колодищи

О разработке проектно-сметной документации по детскому саду и школе в г. Колодищи Перспективы развития внешнеторговых отношений России и КНР

Перспективы развития внешнеторговых отношений России и КНР Перспективы внедрения технологий цифровой экономики на предприятиях ПАО Роснефть

Перспективы внедрения технологий цифровой экономики на предприятиях ПАО Роснефть Теория экономического роста

Теория экономического роста Бухгалтерский баланс

Бухгалтерский баланс Экономика развитого социализма

Экономика развитого социализма Производство Модель инвестиции-сбережения. Эффект мультипликатора

Производство Модель инвестиции-сбережения. Эффект мультипликатора Хозяйство России

Хозяйство России Первая презентация для инвестора

Первая презентация для инвестора Решение задач по экономике с применением математических функций в Microsoft Excel

Решение задач по экономике с применением математических функций в Microsoft Excel Економічна теорія

Економічна теорія В гостях у экономистов

В гостях у экономистов Факторы современного производства

Факторы современного производства Геополитическая интеграция Казахстана

Геополитическая интеграция Казахстана Введение в макроэкономику. Основные макроэкономические показатели

Введение в макроэкономику. Основные макроэкономические показатели Інфляція

Інфляція Особенности осуществления государственного регулирования и саморегулирования оценочной деятельности в Российской Федерации

Особенности осуществления государственного регулирования и саморегулирования оценочной деятельности в Российской Федерации