Слайд 2CONTENTS

Peter’s workforms

About armed force

State services

Batic Expansion and Victory at Poltava

Conclusion

questions

Слайд 3PETER’S WORKFORMS

Peter envisioned the transformation of Russia into a great power, its

state and society based on technology and an organization aimed at maximizing production. Its hallmarks would be a European‑type army and navy (supported by heavy industry to produce arms), planned urban conglomerations after the model of St Petersburg, and large‑scale public works, particularly canals linking the major waterways and productive centres into an integrated economic whole. Peter even commissioned Perry to oversee a canal connecting the Volga and the Don, an over‑ambitious project not realized until the 1930s.

Слайд 4PETER’S WORKFORMS

To supply the armed forces with skilled native personnel, Peter began

founding makeshift educational institutions. He put Farquharson and two English students in charge of the Moscow School of Mathematics and Navigation (housed in the former quarters of a Streltsy regiment); its enrolments grew from 200 pupils in 1703 to over 500 by 1711.

Слайд 5ABOUT ARMED FORCE

The armed forces became the model for the Europeanized society

that Peter doggedly pursued. Utilizing European norms and Muscovite traditions, ‘selfmaintenance’ first of all, he fitfully constructed an integrated force under uniform conditions of service, subject to discipline on hierarchical principles, the officer corps trained in military schools, and the whole managed by a centralized administration guided by written codes. The organization was constantly reshuffled as the ostensibly standing army and expensive fleet showed wanton ways of melting away (or rotting in the case of ships) from continuous mass desertion as well as shortfalls in recruitment and losses to disease and combat.

Слайд 6STATE SERVICES

Military service enshrined the principle of merit as explicated in the

Table of Ranks, the system of fourteen grades (thirteen in practice) applied to all three branches of state service–military, civil, and court. Military ranks enjoyed preference over civil, and all thirteen in the military conferred noble status as opposed to only the top eight in the civil service.

Слайд 7BATIC EXPANSION AND VICTORY AT POLTAVA

The Northern War’s first years saw Peter

and his generals gradually devise a strategy of nibbling away at Swedish dominion in the Baltic while Charles XII pursued Augustus II into Central Europe. Thus the Russians seized control of the Neva river by the spring of 1703, when the Peter and Paul Fortress was founded in the river’s delta, the centre for a new frontier town and naval base.

Слайд 8BATIC EXPANSION AND VICTORY AT POLTAVA

Further westward a fortress‑battery called Kronshlot was

hastily erected near the island of Kotlin, where the harbour of Kronstadt would soon be built. Peter and Menshikov personally led a boat attack on two Swedish warships at the mouth of the Neva in early May that brought Russia’s first naval victory, celebrated by a medal inscribed ‘The Unprecedented Has Happened’. Tsar and favourite were both made knights of the Order of Saint Andrew. In 1704 Dorpat and Narva fell to the Russians, as mounted forces ravaged Swedish Estland and Livland. Among the captives taken in Livland was a buxom young woman, Marta Skavronska, soon to become Russified as Catherine (Ekaterina Alekseevna). She enchanted Peter successively as mistress and common‑law wife, confidante and soul‑mate, empress and successor. Adept at calming his outbursts of rage, she matched his energy and bore him many children.

Слайд 9BATIC EXPANSION AND VICTORY AT POLTAVA

Peter’s broadening political horizons also led him

to arrange marriages of several relatives to foreign rulers. His niece Anna Ivanovna married the duke of Courland in late 1710 and his niece Ekaterina Ivanovna the duke of Mecklenburg‑Schwerin in April 1716 in the presence of Peter, Catherine, and Augustus II. Neither marriage proved successful in personal terms; Anna was widowed almost immediately and Ekaterina returned to Russia with her young daughter in 1722. Tsarevich Alexis’s marriage to Charlotte of Wolfenbüttel in October 1711 proved equally painful for the spouses although it did produce a granddaughter and grandson, the future Peter II. All these matches accented Russia’s rising international stature and resolute entry into the European dynastic marriage market.

Слайд 10CONCLUSION

There is a vast amount of evidence to suggest that Peter was

both a revolutionary and a reformer.

His radical changes in the military, economy and the war can certainly be considered revolutionary, however many of his other reforms were milder in comparison.

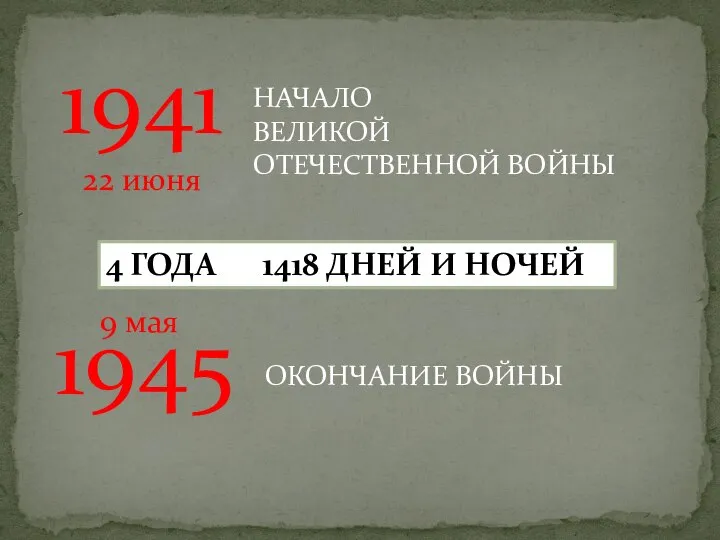

Подвиг моего земляка Березикова Матвея Лавретьевича

Подвиг моего земляка Березикова Матвея Лавретьевича Мой прадедушка - герой Великой Отечественной войны

Мой прадедушка - герой Великой Отечественной войны Историки про Москву

Историки про Москву Крым и Россия

Крым и Россия Музейная экспозиция

Музейная экспозиция Память о войне. Лидия Ивановна Екимова (1924-2008)

Память о войне. Лидия Ивановна Екимова (1924-2008) Презентация на тему Женщины-Герои Советского Союза

Презентация на тему Женщины-Герои Советского Союза  Особенности монархии во Франции: рост королевской власти, парижский парламент, значение генеральных штатов, 1357 год

Особенности монархии во Франции: рост королевской власти, парижский парламент, значение генеральных штатов, 1357 год Презентация на тему Тоталитарные режимы в Европе

Презентация на тему Тоталитарные режимы в Европе  7bec653956c64fc1917556f970506a29

7bec653956c64fc1917556f970506a29 День Победы

День Победы Куранты. История колоколов

Куранты. История колоколов Подготовила Кизилова Анна, уч-ся 6 «А» класса

Подготовила Кизилова Анна, уч-ся 6 «А» класса Культурные инициативы Петра 1. Реформа алфавита

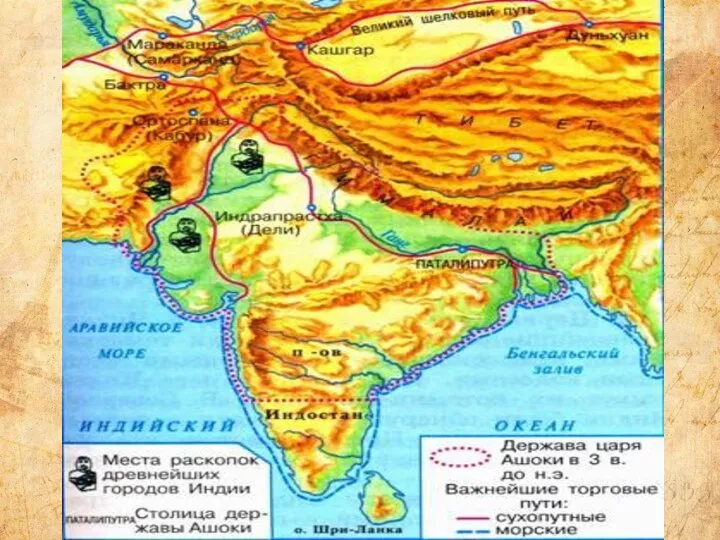

Культурные инициативы Петра 1. Реформа алфавита Индийские касты

Индийские касты Военная реформа

Военная реформа 0f582722-c110-4ae7-9ac3-aa337de26de9

0f582722-c110-4ae7-9ac3-aa337de26de9 Germany. Образование немецкой ассамблеи

Germany. Образование немецкой ассамблеи Презентация на тему Первая мировая война (4 класс)

Презентация на тему Первая мировая война (4 класс)  Бессмертный полк

Бессмертный полк Слобожанская раннесредневековая археологическая экспедиция

Слобожанская раннесредневековая археологическая экспедиция Бунташный век

Бунташный век Великая французская революция

Великая французская революция Абсолютті геохронология

Абсолютті геохронология Лекция 2 Подготовка крестьянской реформы

Лекция 2 Подготовка крестьянской реформы Феодальная раздробленность Руси XII - I половины XIII вв

Феодальная раздробленность Руси XII - I половины XIII вв Сестричка, сестра, сестрица

Сестричка, сестра, сестрица Әтрәчтә калды синең эзләрең

Әтрәчтә калды синең эзләрең