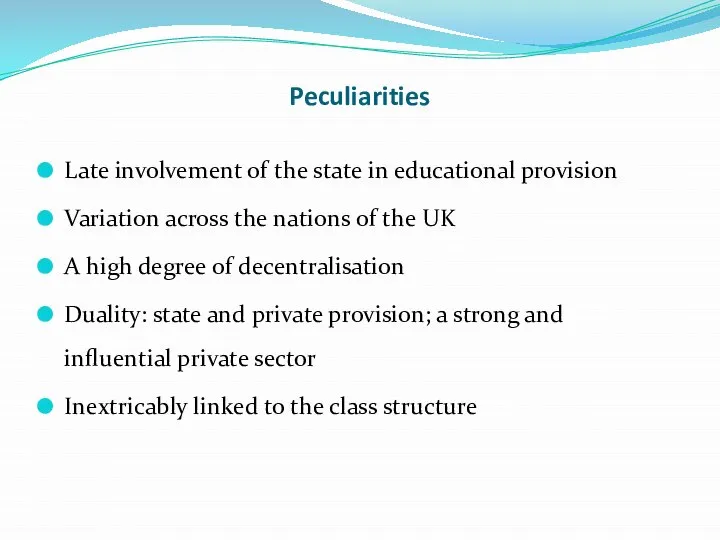

Слайд 2Peculiarities

Late involvement of the state in educational provision

Variation across the nations of

the UK

A high degree of decentralisation

Duality: state and private provision; a strong and influential private sector

Inextricably linked to the class structure

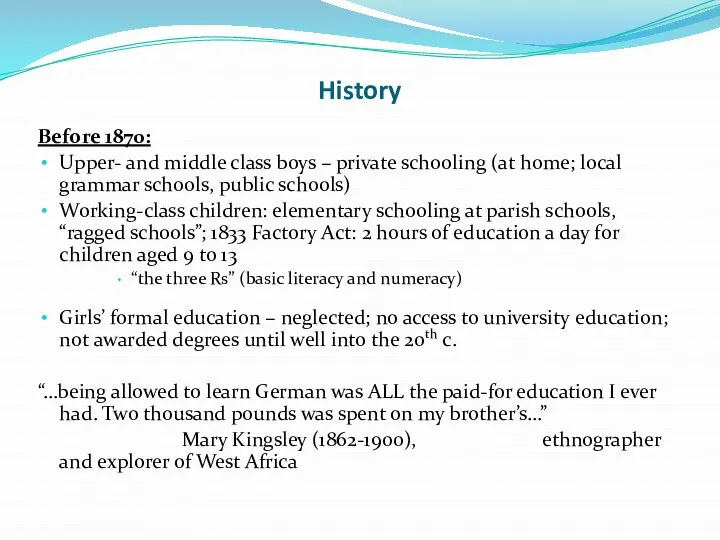

Слайд 3History

Before 1870:

Upper- and middle class boys – private schooling (at home; local

grammar schools, public schools)

Working-class children: elementary schooling at parish schools, “ragged schools”; 1833 Factory Act: 2 hours of education a day for children aged 9 to 13

“the three Rs” (basic literacy and numeracy)

Girls’ formal education – neglected; no access to university education; not awarded degrees until well into the 20th c.

“…being allowed to learn German was ALL the paid-for education I ever had. Two thousand pounds was spent on my brother’s…”

Mary Kingsley (1862-1900), ethnographer and explorer of West Africa

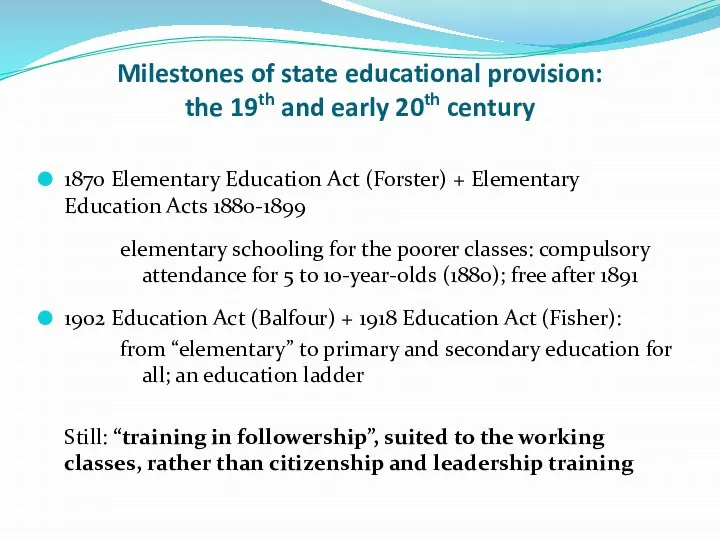

Слайд 4Milestones of state educational provision:

the 19th and early 20th century

1870 Elementary Education

Act (Forster) + Elementary Education Acts 1880-1899

elementary schooling for the poorer classes: compulsory attendance for 5 to 10-year-olds (1880); free after 1891

1902 Education Act (Balfour) + 1918 Education Act (Fisher):

from “elementary” to primary and secondary education for all; an education ladder

Still: “training in followership”, suited to the working classes, rather than citizenship and leadership training

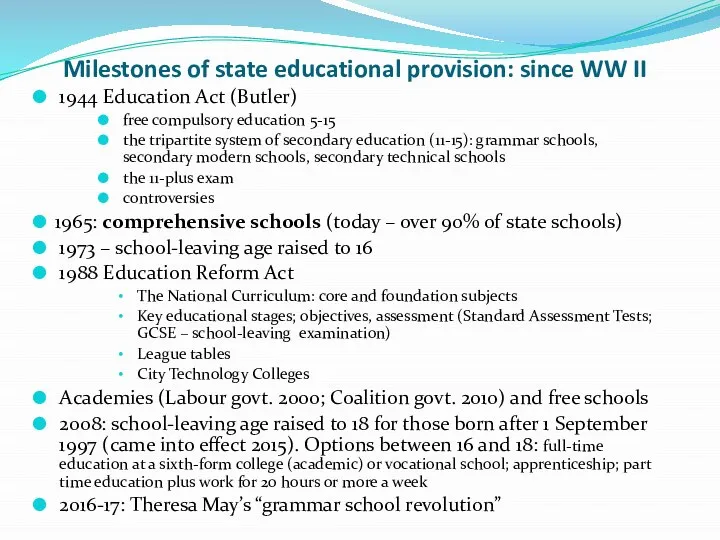

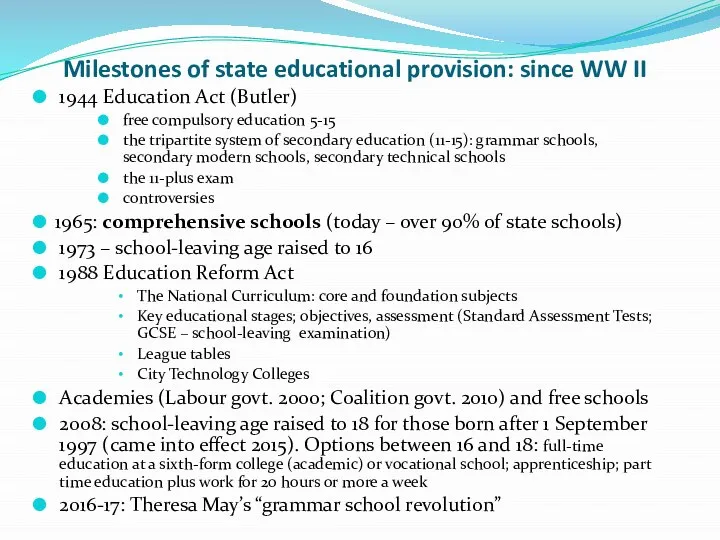

Слайд 5Milestones of state educational provision: since WW II

1944 Education Act (Butler)

free compulsory

education 5-15

the tripartite system of secondary education (11-15): grammar schools, secondary modern schools, secondary technical schools

the 11-plus exam

controversies

1965: comprehensive schools (today – over 90% of state schools)

1973 – school-leaving age raised to 16

1988 Education Reform Act

The National Curriculum: core and foundation subjects

Key educational stages; objectives, assessment (Standard Assessment Tests; GCSE – school-leaving examination)

League tables

City Technology Colleges

Academies (Labour govt. 2000; Coalition govt. 2010) and free schools

2008: school-leaving age raised to 18 for those born after 1 September 1997 (came into effect 2015). Options between 16 and 18: full-time education at a sixth-form college (academic) or vocational school; apprenticeship; part time education plus work for 20 hours or more a week

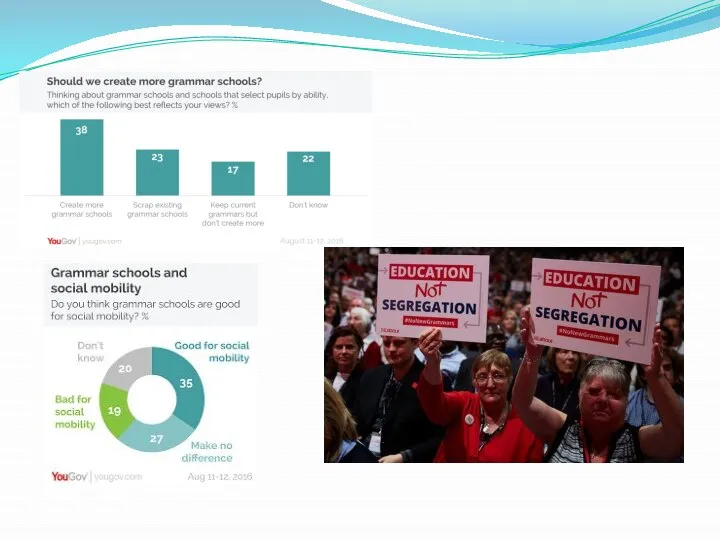

2016-17: Theresa May’s “grammar school revolution”

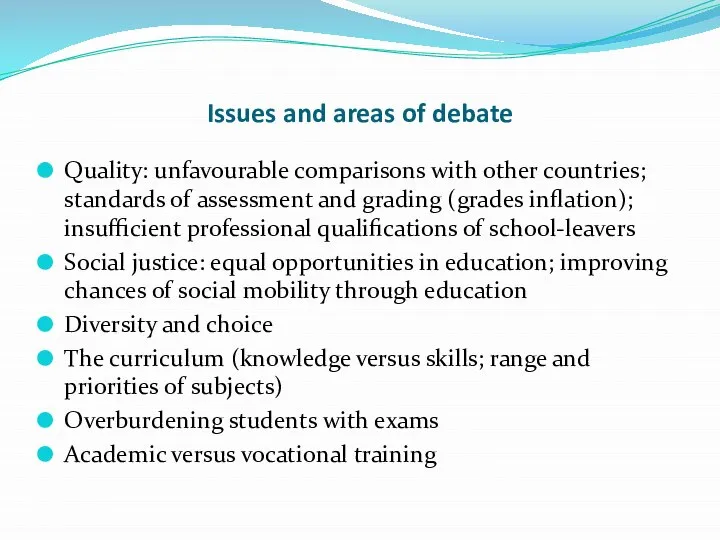

Слайд 7Issues and areas of debate

Quality: unfavourable comparisons with other countries; standards of

assessment and grading (grades inflation); insufficient professional qualifications of school-leavers

Social justice: equal opportunities in education; improving chances of social mobility through education

Diversity and choice

The curriculum (knowledge versus skills; range and priorities of subjects)

Overburdening students with exams

Academic versus vocational training

Слайд 8The “Education hierarchy” sketch (2011)

Слайд 9The private (‘independent’) school sector

Fee-paying schools

Not bound by the National Curriculum

Currently cater

for about 7 per cent of children of 4-18

Different levels of excellence and prestige

Still highly desirable but increasingly unaffordable for the middle class (e.g. – Eton charging £42,501 per year, in 2019)

Intense competition from state schools, due to considerable improvement of state education standards

Слайд 10The institution of the public school

[For more detail read: François Bédarida, “Education

and Class” – self-study text]

The Great Seven: founded 14th-16th c. + lesser public schools

The public school reform of the early 19th century; “Muscular Christianity”

The public school ethos

The role of the public school in the consolidation of the new Victorian elite and the preservation of its values

Targeted by Labour in the 1960s

Response: the “public school revolution” (modernised curriculum; more scholarships for poorer students – improved social inclusiveness; end to some archaic practices; many became co-educational; state-of-the art equipment and facilities; small classes; excellence of teaching staff)

Public schools at present: for and against (at the seminar)

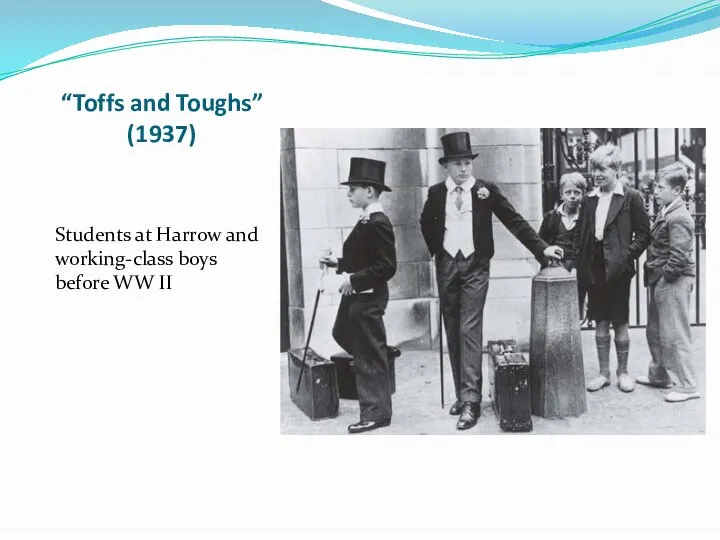

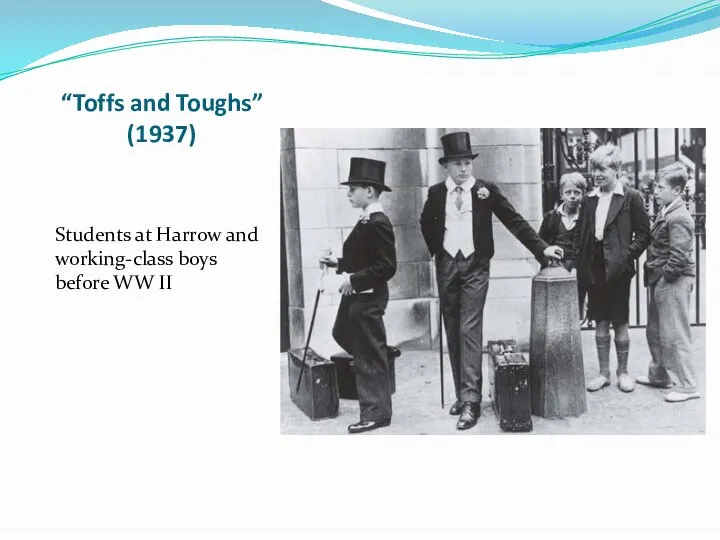

Слайд 11“Toffs and Toughs”

(1937)

Students at Harrow and working-class boys before WW II

Слайд 13 Today’s Etonians … and Hogwarts students

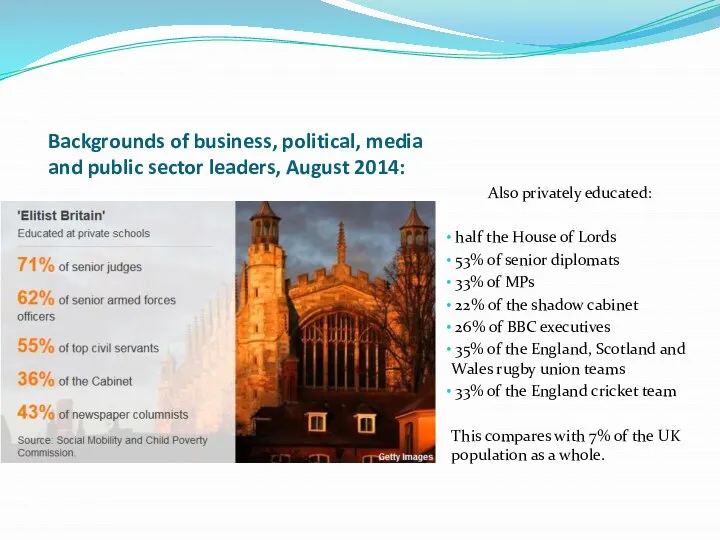

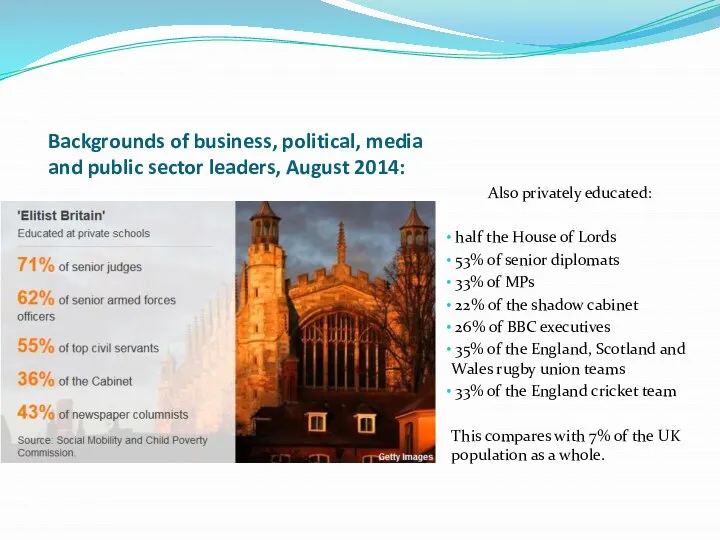

Слайд 14Backgrounds of business, political, media and public sector leaders, August 2014:

Also privately

educated:

half the House of Lords

53% of senior diplomats

33% of MPs

22% of the shadow cabinet

26% of BBC executives

35% of the England, Scotland and Wales rugby union teams

33% of the England cricket team

This compares with 7% of the UK population as a whole.

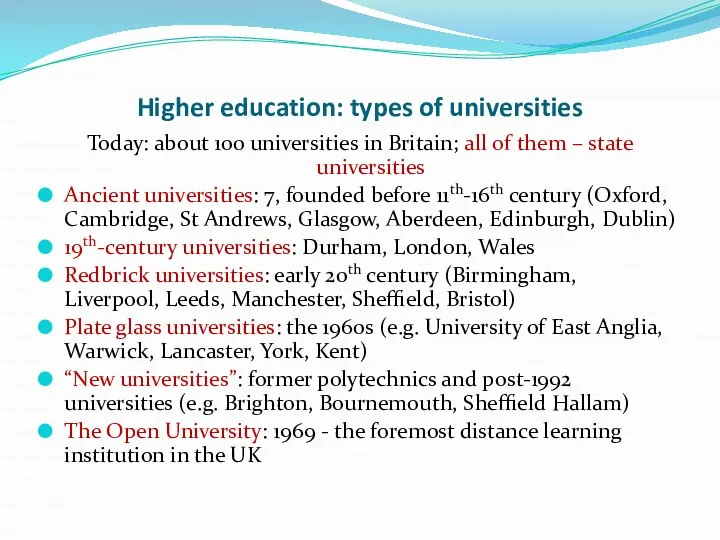

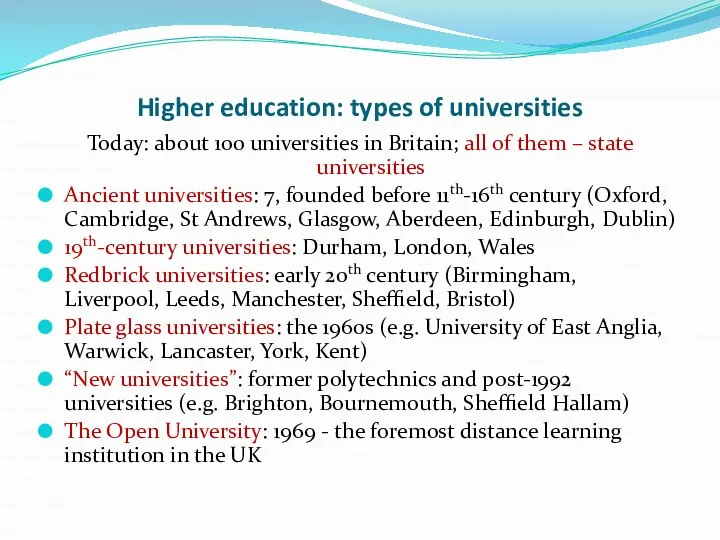

Слайд 15Higher education: types of universities

Today: about 100 universities in Britain; all of

them – state universities

Ancient universities: 7, founded before 11th-16th century (Oxford, Cambridge, St Andrews, Glasgow, Aberdeen, Edinburgh, Dublin)

19th-century universities: Durham, London, Wales

Redbrick universities: early 20th century (Birmingham, Liverpool, Leeds, Manchester, Sheffield, Bristol)

Plate glass universities: the 1960s (e.g. University of East Anglia, Warwick, Lancaster, York, Kent)

“New universities”: former polytechnics and post-1992 universities (e.g. Brighton, Bournemouth, Sheffield Hallam)

The Open University: 1969 - the foremost distance learning institution in the UK

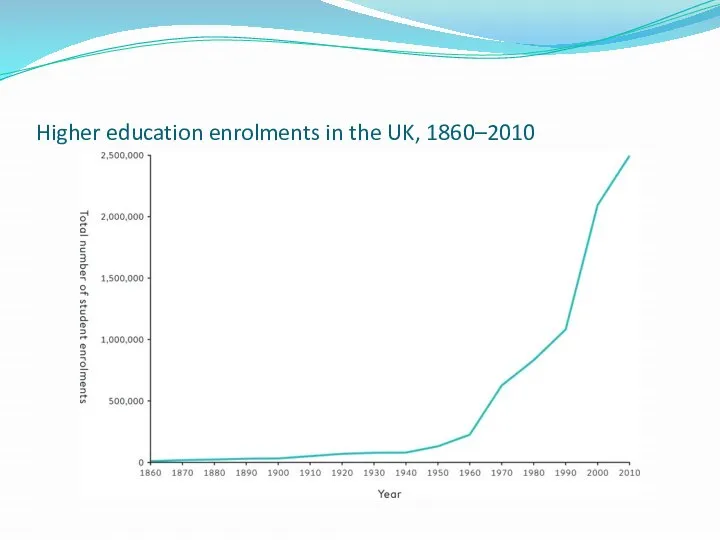

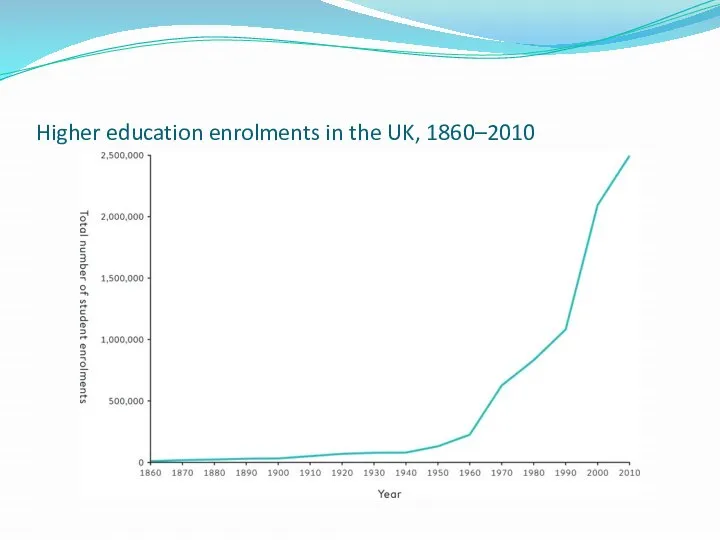

Слайд 16Higher education enrolments in the UK, 1860–2010

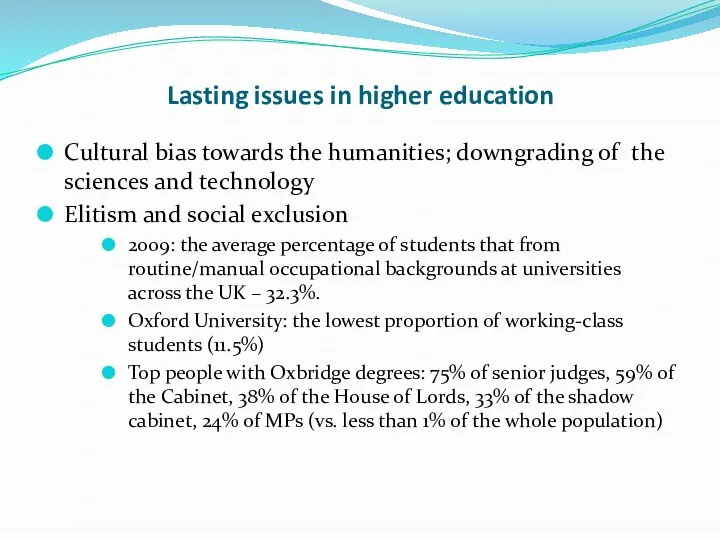

Слайд 17Lasting issues in higher education

Cultural bias towards the humanities; downgrading of the

sciences and technology

Elitism and social exclusion

2009: the average percentage of students that from routine/manual occupational backgrounds at universities across the UK – 32.3%.

Oxford University: the lowest proportion of working-class students (11.5%)

Top people with Oxbridge degrees: 75% of senior judges, 59% of the Cabinet, 38% of the House of Lords, 33% of the shadow cabinet, 24% of MPs (vs. less than 1% of the whole population)

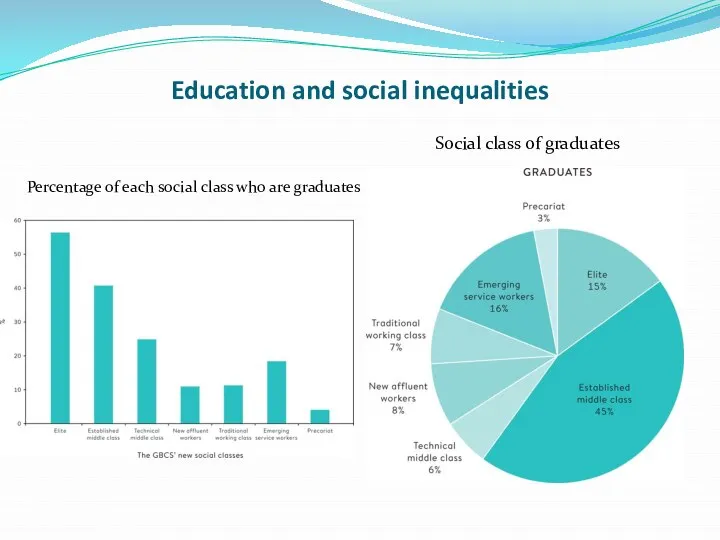

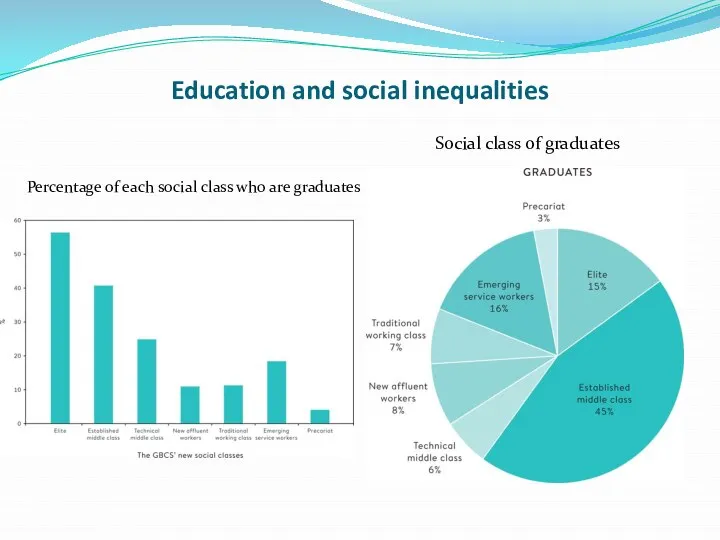

Слайд 18Education and social inequalities

Percentage of each social class who are graduates

Social class

of graduates

Слайд 19Education and the British political elite

Since Winston Churchill every British prime minister

who went to university attended the same English institution, the University of Oxford, except Gordon Brown, who went to Edinburgh. Of fifty-five British prime ministers since Horace Walpole, more than a third, twenty, were products of the same English school, Eton.

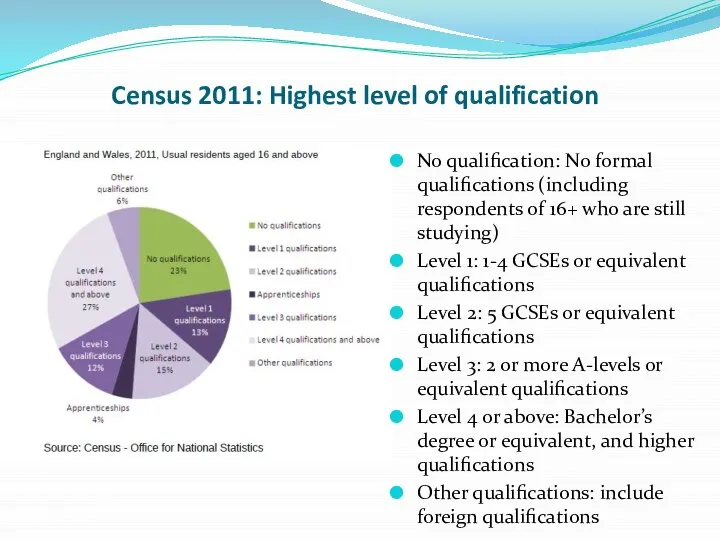

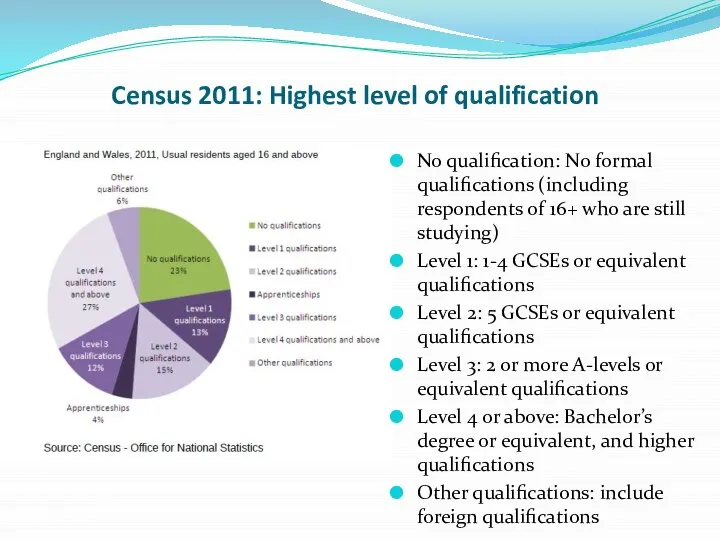

Слайд 20Census 2011: Highest level of qualification

No qualification: No formal qualifications (including respondents

of 16+ who are still studying)

Level 1: 1-4 GCSEs or equivalent qualifications

Level 2: 5 GCSEs or equivalent qualifications

Level 3: 2 or more A-levels or equivalent qualifications

Level 4 or above: Bachelor’s degree or equivalent, and higher qualifications

Other qualifications: include foreign qualifications

I can see

I can see Manufacturing

Manufacturing Prepositions in Time Expressions

Prepositions in Time Expressions Gucci is an Italian luxury brand

Gucci is an Italian luxury brand English for children

English for children Treasure maps

Treasure maps Merry Christmas

Merry Christmas English lesson

English lesson Paris the city of love

Paris the city of love Sprawling cities

Sprawling cities Перевод Причастия

Перевод Причастия Conditionals

Conditionals Английский с Karst

Английский с Karst Circus (1)

Circus (1) Science Fiction. Upper-Intermediate English file

Science Fiction. Upper-Intermediate English file Методическое пособие к учебнику Rainbow English, 3 класс Афанасьевой О. В

Методическое пособие к учебнику Rainbow English, 3 класс Афанасьевой О. В Правила оформления письма

Правила оформления письма The 6th of April Monday

The 6th of April Monday Wolf

Wolf Our Future Profession Учитель английского языка МБОУ «Новотроицкая СОШ», Альметьевский район

Our Future Profession Учитель английского языка МБОУ «Новотроицкая СОШ», Альметьевский район Презентация к уроку английского языка "The radio invention" -

Презентация к уроку английского языка "The radio invention" -  Shopping

Shopping News report

News report Building Fluency for All Students

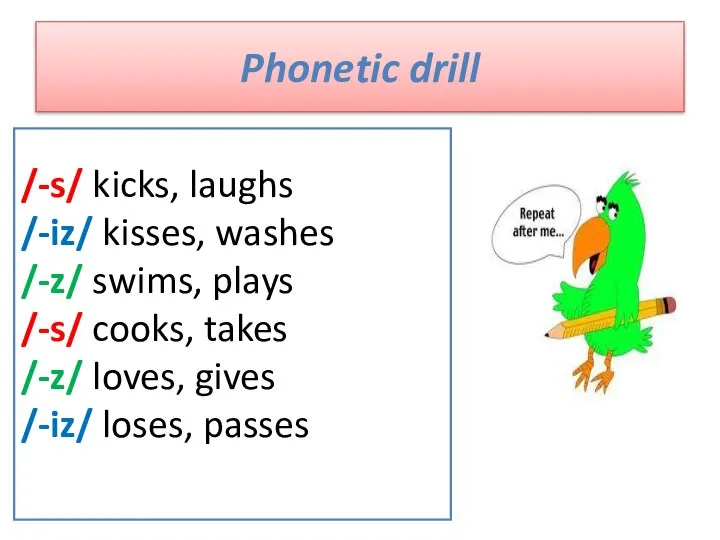

Building Fluency for All Students Phonetic drill

Phonetic drill Презентация к уроку английского языка "Вариативная часть" -

Презентация к уроку английского языка "Вариативная часть" -  Theoretical, practical and methodical aspects of stockpile management of the enterprise

Theoretical, practical and methodical aspects of stockpile management of the enterprise The world quiz

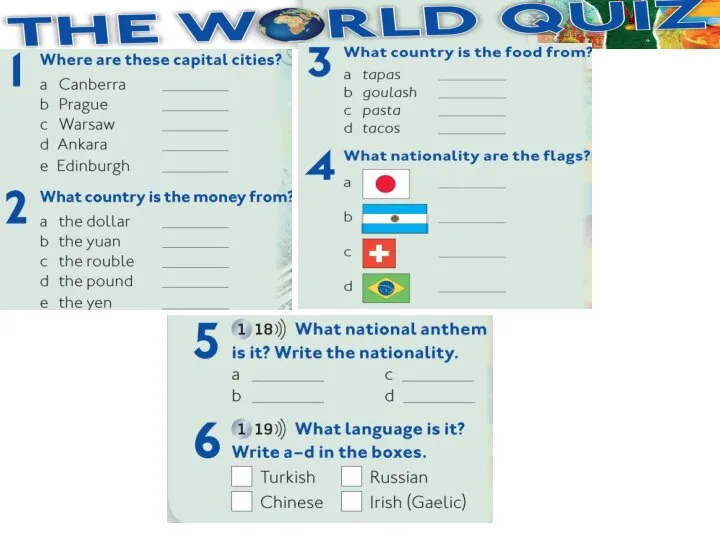

The world quiz