Слайд 2How do we know how Old English was pronounced?

Obviously there are no

recordings.

Largely guesswork but not totally.

Слайд 3

Grounds for reconstruction of Old English/Anglo-Saxon pronunciation:

1) As all new written

languages, Old English had predominantly phonetic spelling;

2) Comparison with cognate langugages (German, Scandinavian languages);

3) Comparison with Modern English (changes not arbitrary but follow sound laws; without a sound law there is no reason to believe the pronunciation has changed).

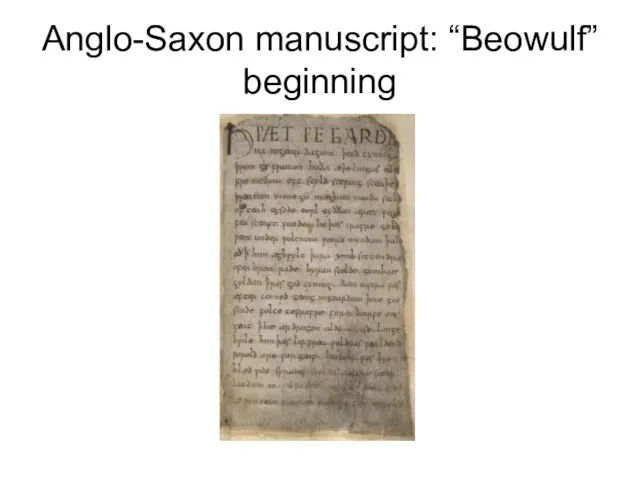

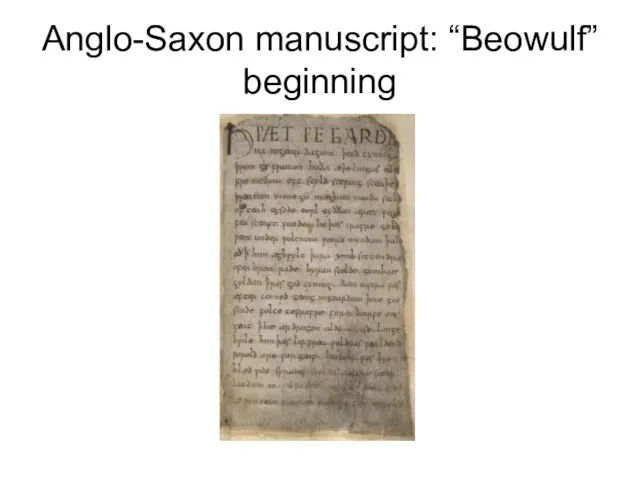

Слайд 4Anglo-Saxon manuscript: “Beowulf” beginning

Слайд 5This is what the text might have sounded like

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LP2FyVbymTg

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4L7VTH8ii_8

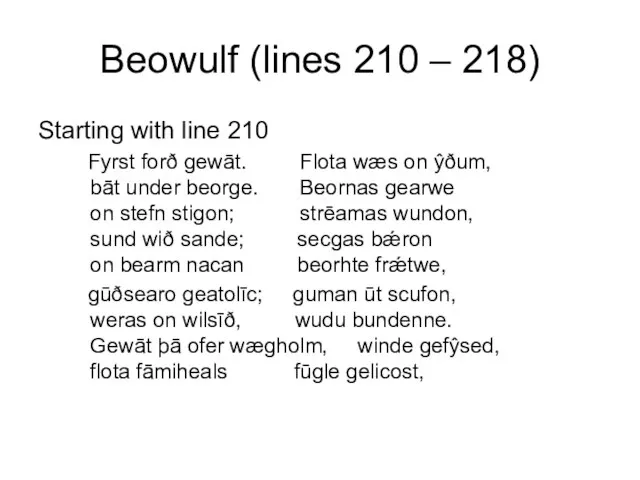

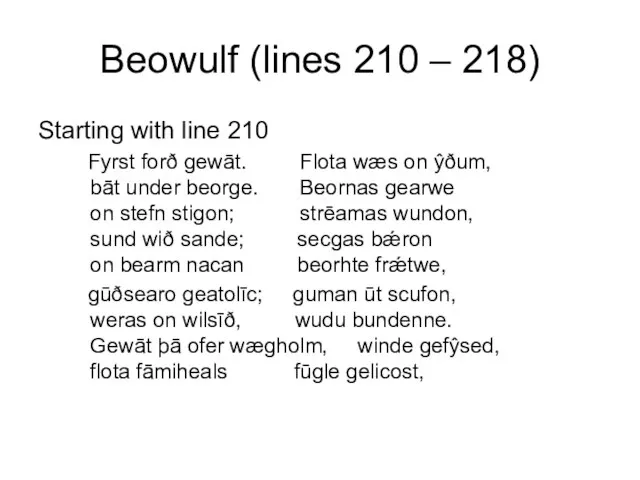

Слайд 6Beowulf (lines 210 – 218)

Starting with line 210

Fyrst forð gewāt.

Flota wæs on ŷðum,

bāt under beorge. Beornas gearwe

on stefn stigon; strēamas wundon,

sund wið sande; secgas bǽron

on bearm nacan beorhte frǽtwe,

gūðsearo geatolīc; guman ūt scufon,

weras on wilsīð, wudu bundenne.

Gewāt þā ofer wægholm, winde gefŷsed,

flota fāmiheals fūgle gelicost,

Слайд 7For reading, check also the following link

http://www.beowulftranslations.net/beorefs/beowulf-audio-0194a-0224a-benslade.mp3

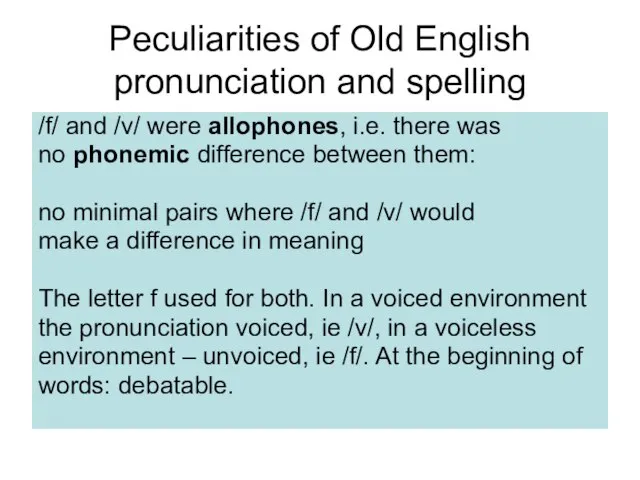

Слайд 8Peculiarities of Old English pronunciation and spelling

/f/ and /v/ were allophones, i.e.

there was

no phonemic difference between them:

no minimal pairs where /f/ and /v/ would

make a difference in meaning

The letter f used for both. In a voiced environment

the pronunciation voiced, ie /v/, in a voiceless

environment – unvoiced, ie /f/. At the beginning of

words: debatable.

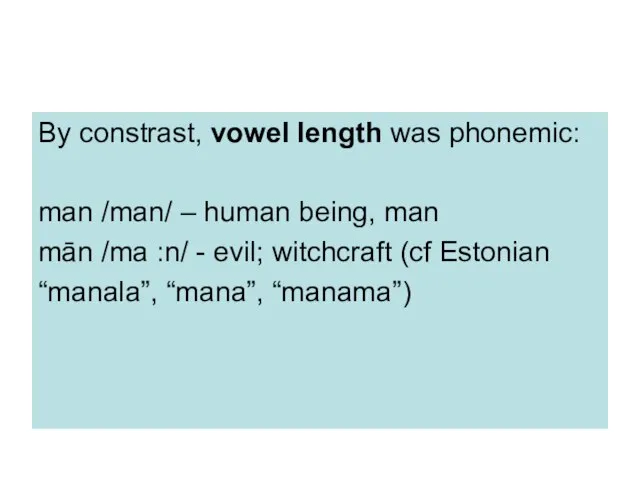

Слайд 9By constrast, vowel length was phonemic:

man /man/ – human being, man

mān /ma

:n/ - evil; witchcraft (cf Estonian

“manala”, “mana”, “manama”)

Слайд 10In old manuscripts vowel length

indicated by ´ (like a stress mark),

in modern editions a strike over the

vowel.

Слайд 11The scribes proceeded from the Latin

alphabet. However, there were sounds in

Old English that Latin did not have.

Solutions had to be found.

/æ/ - the sound is between /a/ and /e/, so a

digraph (Greek for “two + letter”) was created: æ

(A similar thing in French, the digraph œ still in

use, e.g. œil – eye)

Слайд 12Old English had /ü/ like other Germanic

languages today (e.g. German). (The

sound

was lost during the Middle English period).

Latin had no such sound. y (a form of i) was

used to indicate the sound. How do we

know? Cf Old English “fyrst” and Modern

German “Fürst”, Estonian “vürst” (an old

Low German loan).

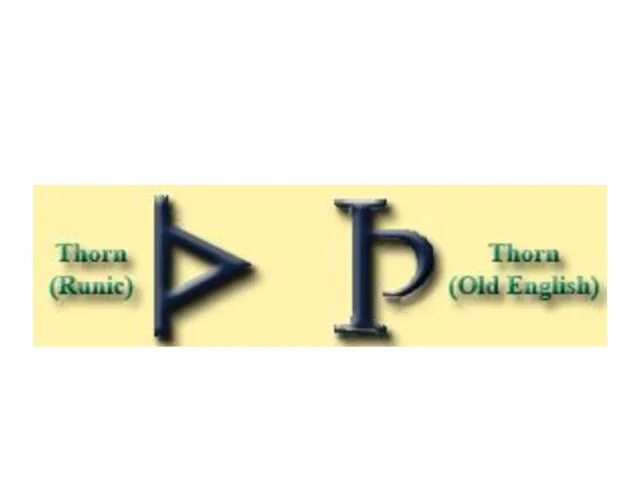

Слайд 13 In Old English texts we come across several

runic letters

modified Latin

letters.

Both used to denote sounds that Old English had

and Latin did not.

Thorn-letter (runic) and edh-letter (modified Latin

d) for the /ө/ sound (close to t and d) used

indiscriminately for both the voiceless and the

voiced variant.

Слайд 14 Thorn, or þorn (Þ, þ), is a letter in the Anglo-Saxon and

Icelandic alphabets. It was also used in medieval Scandinavia, but was later replaced with the digraph th. The letter originated from a rune in the Elder Fuþark, called thorn in the Anglo-Saxon and thorn or thurs ("Thor", "giant") in the Scandinavian rune poems, its reconstructed Proto-Germanic name being *Thurisaz.

It has the sound of either a voiceless dental fricative, like th as in the English word thick, or a voiced dental fricative, like th as in the English word the. (In Modern Icelandic the usage is restricted to the former. The voiced form is represented with the letter eth (Ð, ð), though eth can be unvoiced, depending on its position within a sentence).

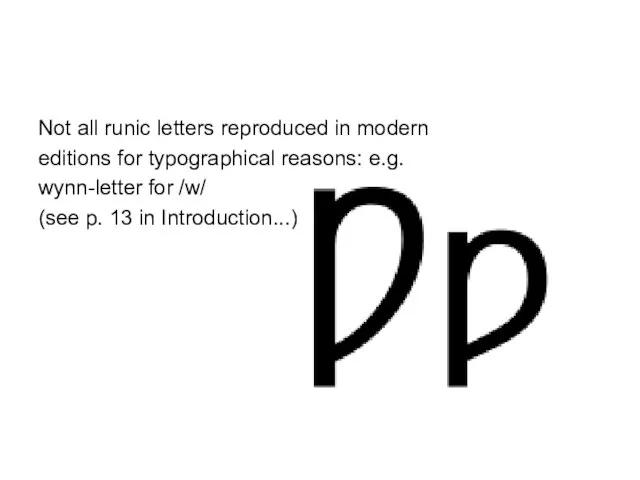

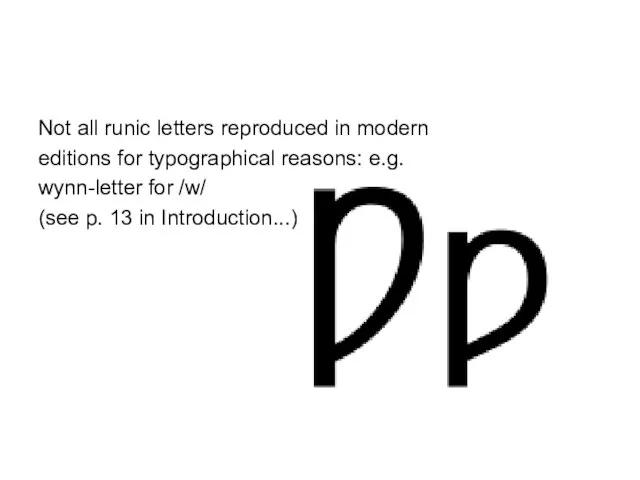

Слайд 16Not all runic letters reproduced in modern

editions for typographical reasons: e.g.

wynn-letter for /w/

(see p. 13 in Introduction...)

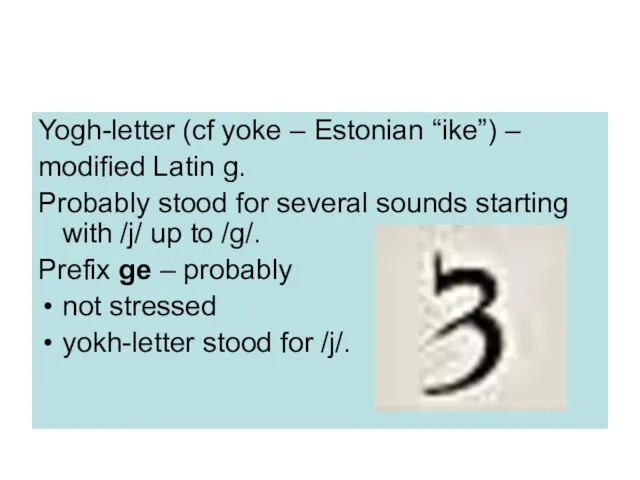

Слайд 17Yogh-letter (cf yoke – Estonian “ike”) –

modified Latin g.

Probably stood

for several sounds starting with /j/ up to /g/.

Prefix ge – probably

not stressed

yokh-letter stood for /j/.

Слайд 18Reasons for surmising this:

The prefix is still there in German (Past Participle,

e.g. gehen, ging. gegangen). It is not stressed in German.

The prefix was lost during the Middle English times (geholpan – holpen), it is easier to drop unstressed syllables.

The middle version was /i/ (spelt in Middle English as y): y-ronne (run Past participle). More logical that /je/ turns into /i/ than that /ge/ turns into /i/. Modern English still had the obsolete form “yclept” – so-called.

Слайд 19C stood for /k/, except when there was a dot on it

– then it stood for /kj/ which later turned into /tS/ in the Southern part of Britain, but not in the Northern part.

Cf ċiriċe – church, but in Scottish English (i.e. Northern English) Auld Kirk, Free Kirk (German Kirche, Est. kirik – Low German loanword).

Слайд 20Cg – probably /kjkj/ which later turned into

/dž/.

Слайд 21/r/ - trilled, rolled, again preserved in Scottish English.

/r/ was still

rolled in Shakespeare’s time

(“When that warlike Harry ...”)

Слайд 22h – pronounced in three ways:

At the beginning of a word/syllable –

like in Present-Day English, e.g. hus - /hu:s/ (house)

At the end of a syllable after a front vowel (/e/,/i/, /æ/) – like the present-day German ich-Laut.

At the end of a syllable after a consonant or a back vowel (/a/, /u/, /o/) - like the present-day German ach-Laut. Ach-Laut has survived in Scottish English (which is more archaic!), e.g. loch (in Received Pronunciation ends in /k/)

Слайд 23A vowel between /a/ and /o/ (before m and

n). Swedish uses

a special letter - å, Old

English: a and o interchangeably (and/ond).

Слайд 24Phonotactic rules

In every language some sequences of sounds are permitted, others not.

For instance, Present-Day British English never has /h/ or /r/ at the end of a syllable (American English has a kind of /r/ at the end of a syllable), whereas Old and Middle English had. Old English also had, for instance /kn/ at the beginning of words (“kniht” and “niht” were not pronounced in the same way!), etc. Cf also “stefn” in the text.

Слайд 25 For a long time, Estonian did not “permit” consonant clusters at the

beginning of a word, hence, loanwords lost them (cf. German Strand > Estonian rand), later loans (German Glas > Estonian klaas) already retained them (this will become relevant later in the course as we compare Old English and Middle English words and the corresponding loans in Estonian).

Слайд 26Phonotactic rules account for the so-called

“empty” words – could be in

the particular

language, sound like words of the language

but just by chance so not have a meaning.

Perfect example in Lewis Carroll’s

“Jabberwocky”.

Слайд 27JABBERWOCKY

Lewis Carroll

(from Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, 1872)

First

stanza:

“`Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe:

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe”.

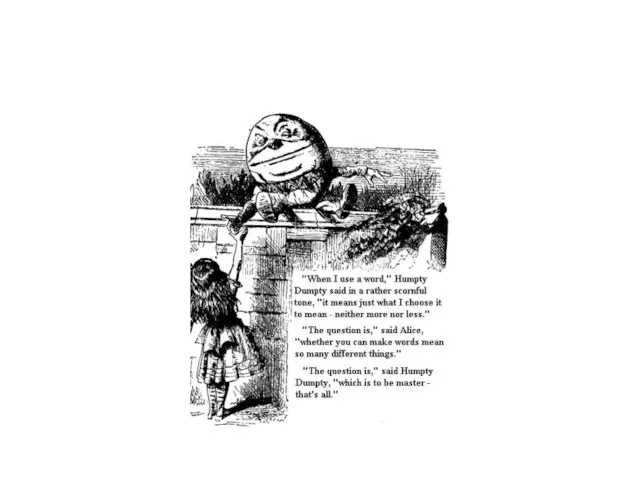

Слайд 28The words sound like English words (unlike,

for instance, something like prsotr

– totally

invented by me, or vzglyad (взгляд):

Russian for “look” – example by Whorter). In

“Through the Looking-Glass”, Humpty-

Dumpty, who hears the poem, gives his own

meanings to most of the words.

Слайд 30(Illustrations to Alice in Wonderland by John Tenniel)

MadameTussaud’s Музей Восковых фигур Мадам Тюссо

MadameTussaud’s Музей Восковых фигур Мадам Тюссо Место учебного исследования в программе Intel «Обучение для будущего»

Место учебного исследования в программе Intel «Обучение для будущего» Потребительские кредиты

Потребительские кредиты Организация пастбищного содержания животных

Организация пастбищного содержания животных А

А Структура ВС РФ

Структура ВС РФ Северная Америка

Северная Америка «Как продолжается детство»

«Как продолжается детство» Молодые менеджеры и предприниматели Кубани

Молодые менеджеры и предприниматели Кубани Презентация на тему Углекислый газ СО2

Презентация на тему Углекислый газ СО2  Солнце воздух и вода – наши лучшие друзья

Солнце воздух и вода – наши лучшие друзья Лапта. История развития

Лапта. История развития Что такое система LanDrive ? LanDrive – это универсальная система управления по витой паре. Предназначена для автоматического и централиз

Что такое система LanDrive ? LanDrive – это универсальная система управления по витой паре. Предназначена для автоматического и централиз Презентация на тему Экологические кризисы и экологические катастрофы

Презентация на тему Экологические кризисы и экологические катастрофы История Громова Процессы на постсоветском пространстве

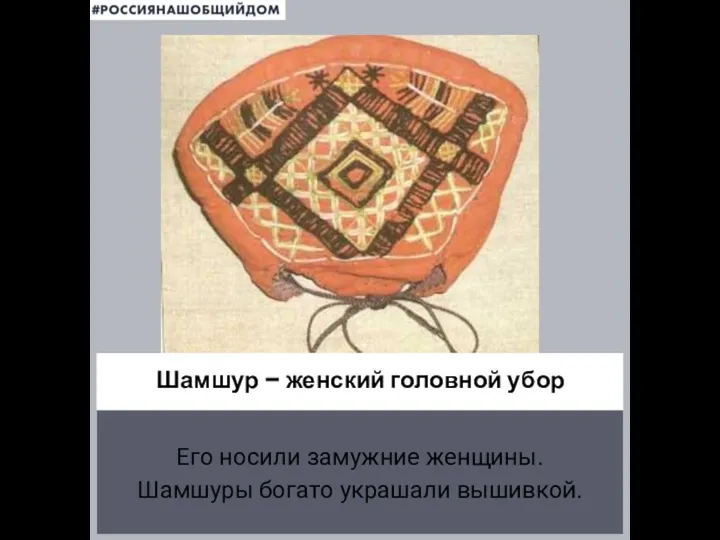

История Громова Процессы на постсоветском пространстве Шамшур

Шамшур Приобщение дошкольников к народной культуре в разных видах музыкальной деятельности»

Приобщение дошкольников к народной культуре в разных видах музыкальной деятельности» Тема урока

Тема урока Понятие о причастном обороте. Знаки препинания в предложениях с причастными оборотами. 6 класс

Понятие о причастном обороте. Знаки препинания в предложениях с причастными оборотами. 6 класс Презентация на тему Свет и его законы

Презентация на тему Свет и его законы  Презентация "Николай I и его портреты в изобразительном искусстве" - скачать презентации по МХК

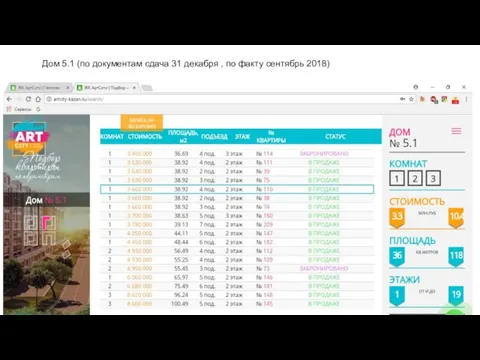

Презентация "Николай I и его портреты в изобразительном искусстве" - скачать презентации по МХК Art City. Подбор квартиры

Art City. Подбор квартиры Фалсафа - 5

Фалсафа - 5 врол

врол Бабаево – взгляд с любовью (городской путеводитель)

Бабаево – взгляд с любовью (городской путеводитель) Бесприборные тесты для подтверждения ВИЧ-Инфекции

Бесприборные тесты для подтверждения ВИЧ-Инфекции Техника безопасностииорганизация рабочего места

Техника безопасностииорганизация рабочего места Конспект урока по окружающему миру (история)с использованием информационно-коммуникационных технологий (3 класс, программа 1-4).

Конспект урока по окружающему миру (история)с использованием информационно-коммуникационных технологий (3 класс, программа 1-4).