Содержание

- 2. Why study history of a language? To see how and why languages in general change To

- 3. Causes for language change Language-internal Language-external

- 4. Language-internal causes There is always variation in the speech of members of a group (idiolects!) Variation

- 5. Language-external causes Influence of other languages,i.e. language contact – mainly borrowing.

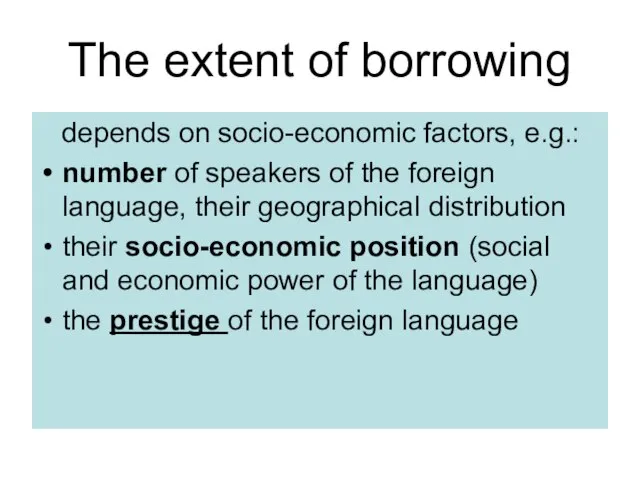

- 6. The extent of borrowing depends on socio-economic factors, e.g.: number of speakers of the foreign language,

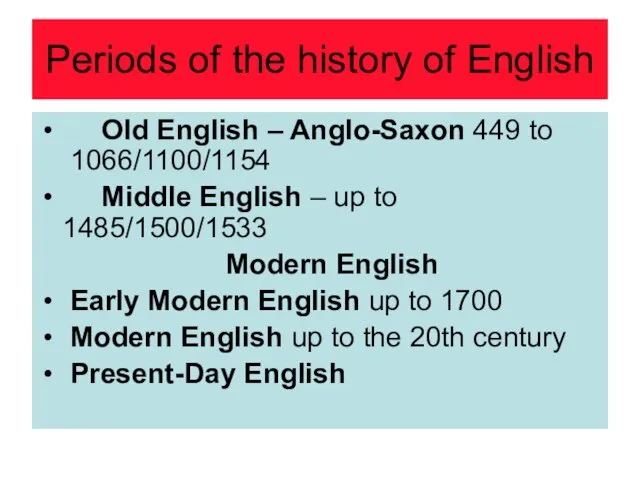

- 7. Periods of the history of English Old English – Anglo-Saxon 449 to 1066/1100/1154 Middle English –

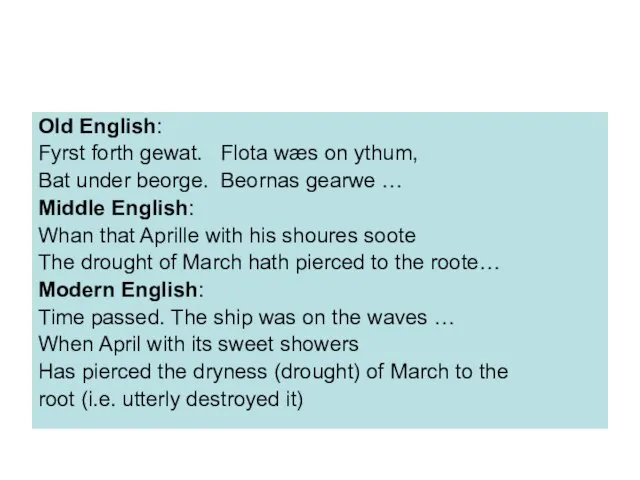

- 8. Old English: Fyrst forth gewat. Flota wæs on ythum, Bat under beorge. Beornas gearwe … Middle

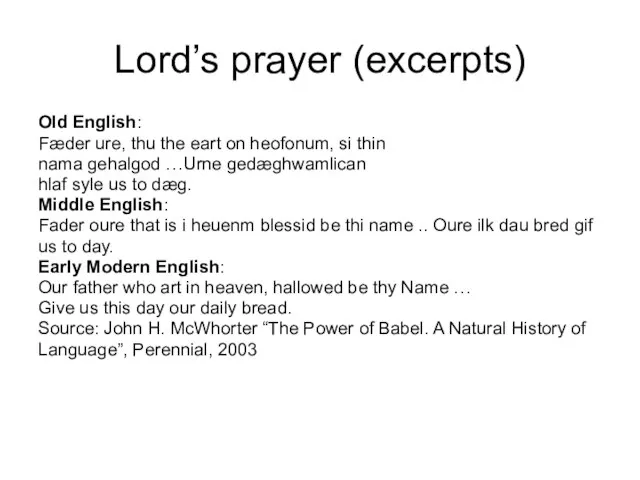

- 9. Lord’s prayer (excerpts) Old English: Fæder ure, thu the eart on heofonum, si thin nama gehalgod

- 10. Periods in the History of English I: Old English (Anglo-Saxon) 449 – first Anglo-Saxons leave the

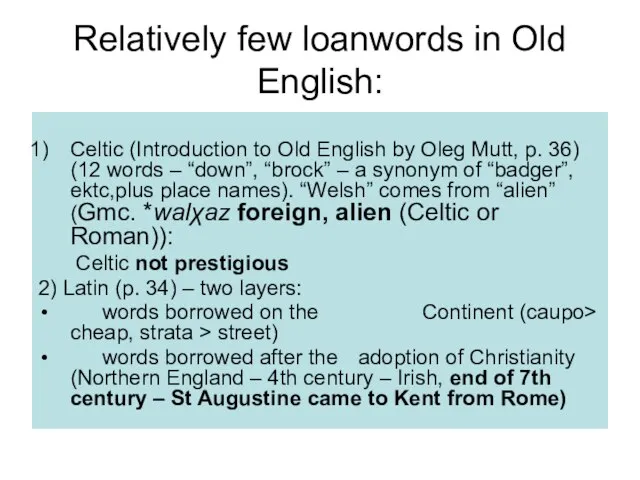

- 11. Relatively few loanwords in Old English: Celtic (Introduction to Old English by Oleg Mutt, p. 36)

- 12. Celtic loans “Cross” etymology: Middle English cros, from Old English, probably from Old Norse kross, from

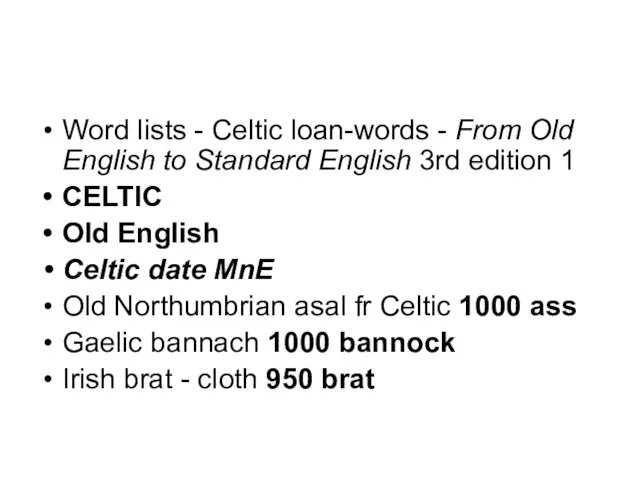

- 13. Word lists - Celtic loan-words - From Old English to Standard English 3rd edition 1 CELTIC

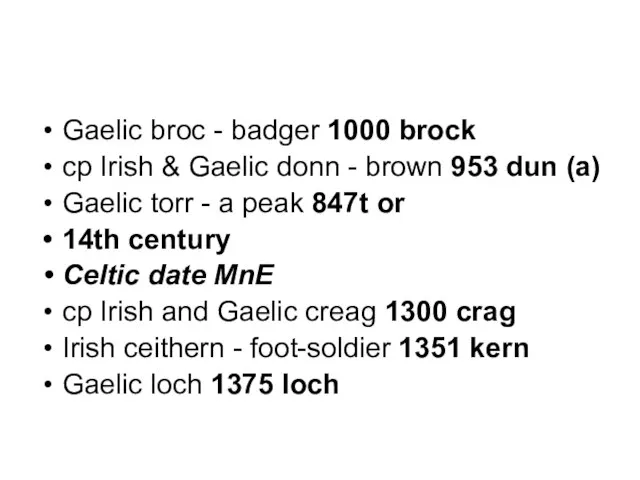

- 14. Gaelic broc - badger 1000 brock cp Irish & Gaelic donn - brown 953 dun (a)

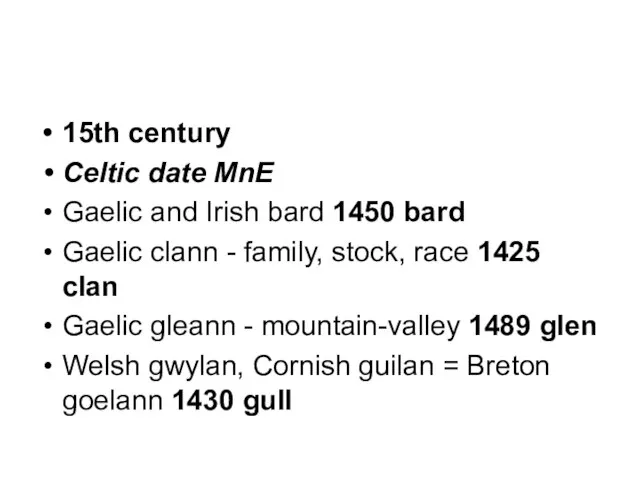

- 15. 15th century Celtic date MnE Gaelic and Irish bard 1450 bard Gaelic clann - family, stock,

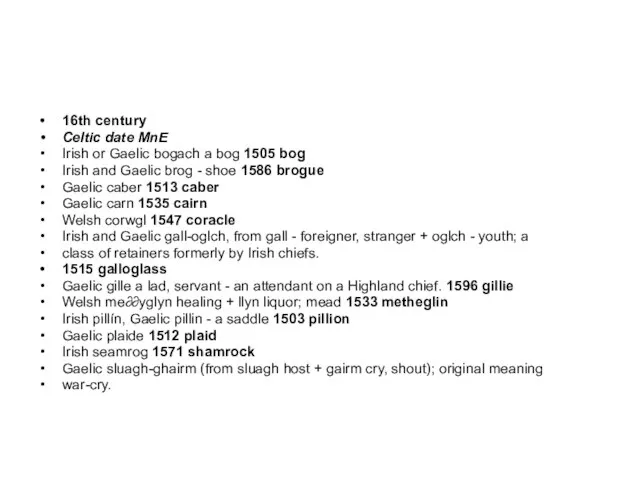

- 16. 16th century Celtic date MnE Irish or Gaelic bogach a bog 1505 bog Irish and Gaelic

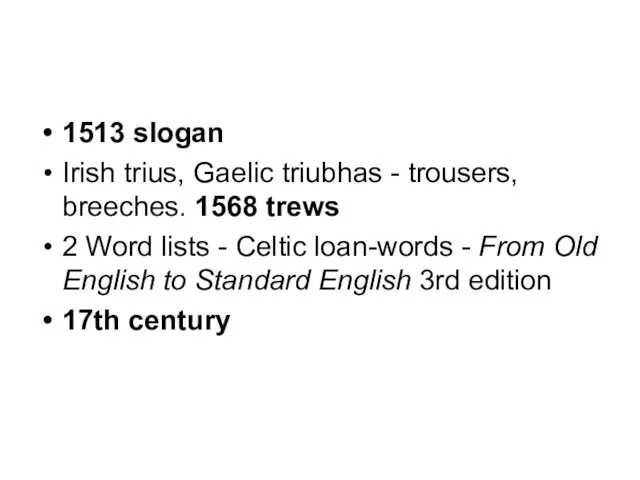

- 17. 1513 slogan Irish trius, Gaelic triubhas - trousers, breeches. 1568 trews 2 Word lists - Celtic

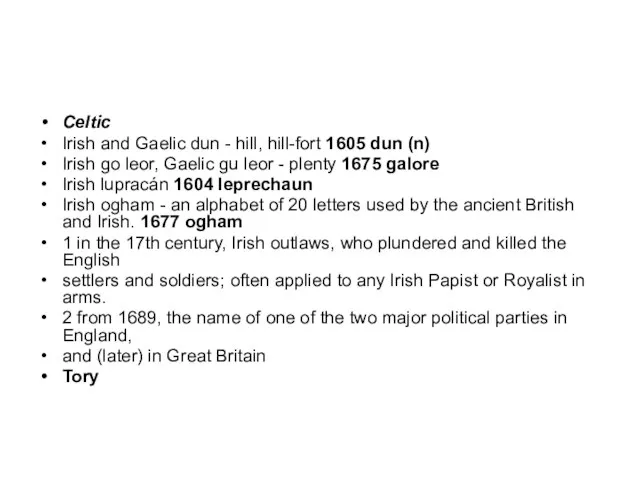

- 18. Celtic Irish and Gaelic dun - hill, hill-fort 1605 dun (n) Irish go leor, Gaelic gu

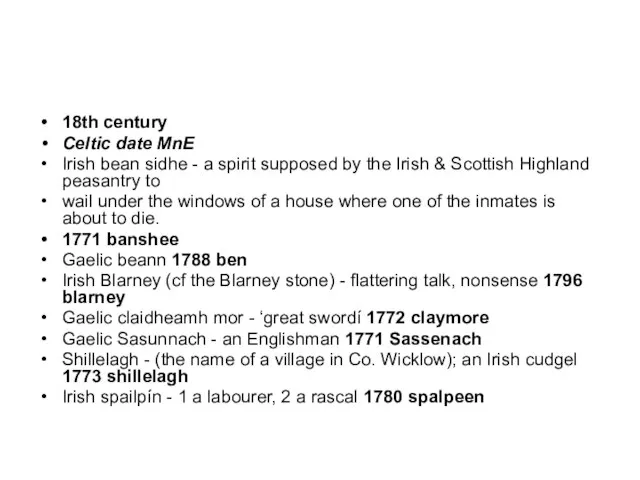

- 19. 18th century Celtic date MnE Irish bean sidhe - a spirit supposed by the Irish &

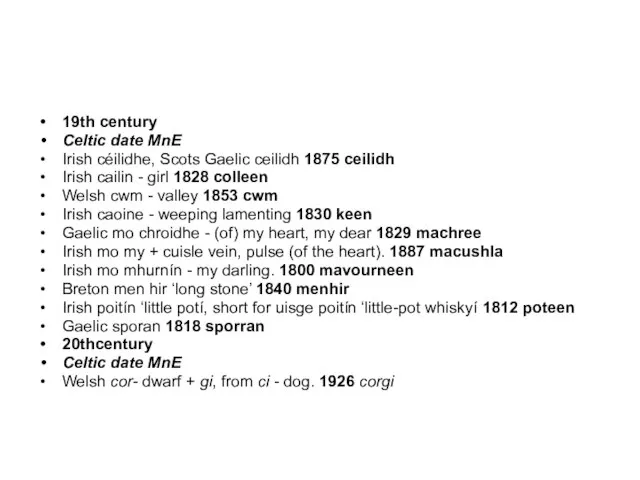

- 20. 19th century Celtic date MnE Irish céilidhe, Scots Gaelic ceilidh 1875 ceilidh Irish cailin - girl

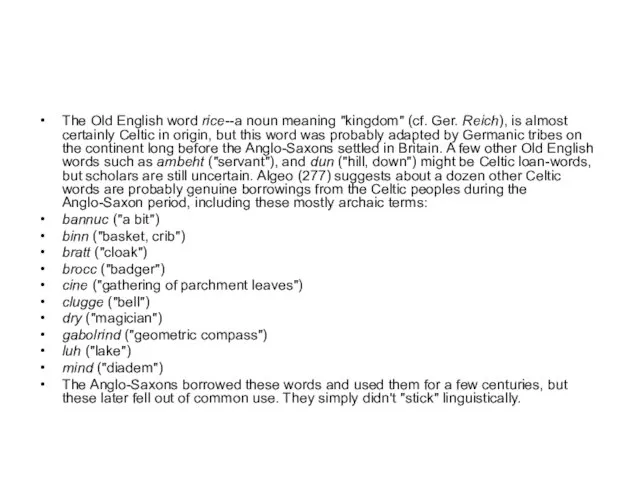

- 21. The Old English word rice--a noun meaning "kingdom" (cf. Ger. Reich), is almost certainly Celtic in

- 22. In general, two types of Celtic loan words were likely targets of permanent Anglo-Saxon adaptation before

- 23. (2) Latin words the Celts borrowed from Rome, which were in turn borrowed by the Anglo-Saxon

- 24. Ironically, the largest number of Celtic borrowings occurred not during the Anglo-Saxon period, when the Angles

- 25. Celtic languages today Welsh Irish (Gaelic, 1% native speakers, unpopular in Ireland, however, official language of

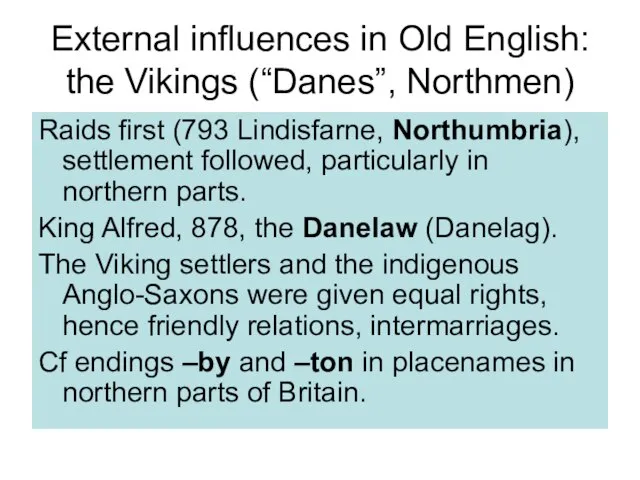

- 26. External influences in Old English: the Vikings (“Danes”, Northmen) Raids first (793 Lindisfarne, Northumbria), settlement followed,

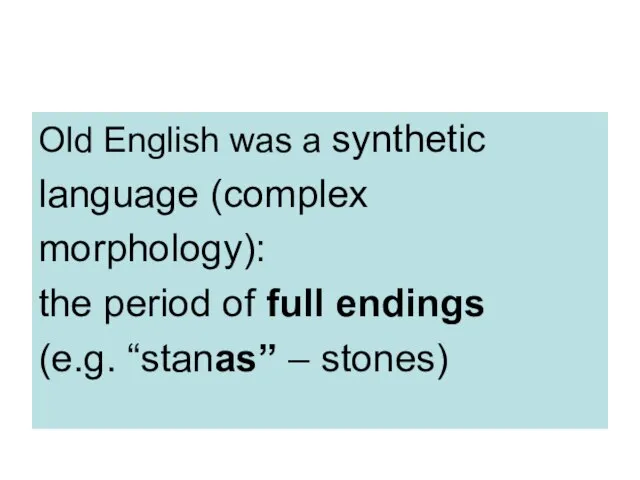

- 27. Old English was a synthetic language (complex morphology): the period of full endings (e.g. “stanas” –

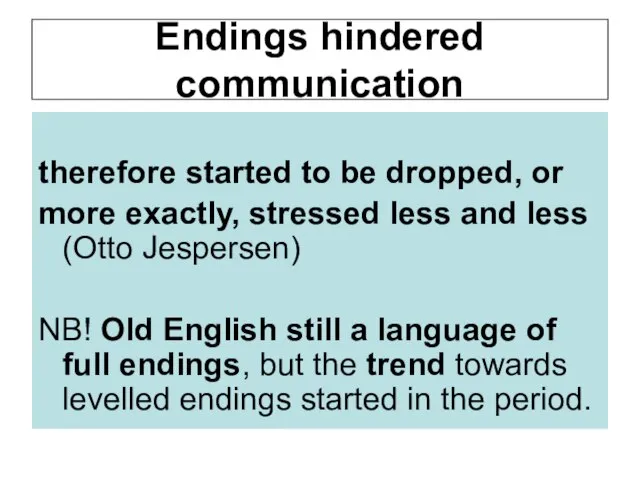

- 28. Endings hindered communication therefore started to be dropped, or more exactly, stressed less and less (Otto

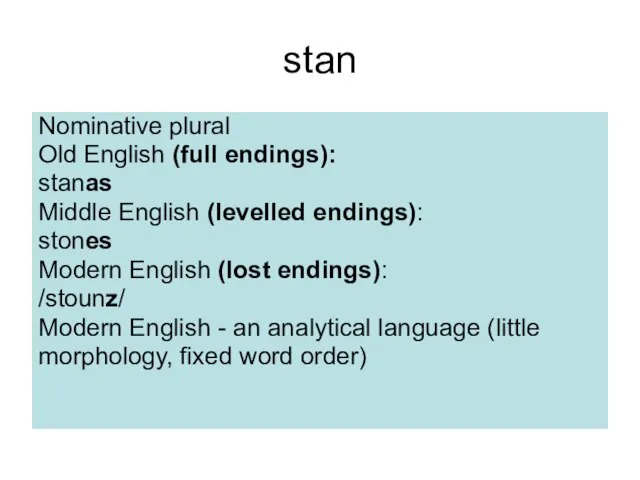

- 29. stan Nominative plural Old English (full endings): stanas Middle English (levelled endings): stones Modern English (lost

- 30. Old English fairly similar to present-day German and Scandinavian languages (and particularly present-day Icelandic!)

- 31. Trend towards the loss of vowels In Present-day English, /ə/ the most common vowel (20% of

- 32. Norman barons lived among Anglo-Saxons. Words related to court, army, justice, fashion etc. borrowed.

- 33. Periods of the history of English II: Middle English 1066 – the Battle of Hastings During

- 34. Teutonic = Germanic Otto Jespersen: “The Norman invasion broke the proud Teutonic backbone of the English

- 35. However: Flower, forest, valley, river*, face** – Norman French loans (Anglo-Saxon bloom, cf German Blum, wood,

- 36. The re-emergence of English Starting with the 14th century. A relatively unique phenomenon: conquerors do not

- 37. Why the re-emergence?

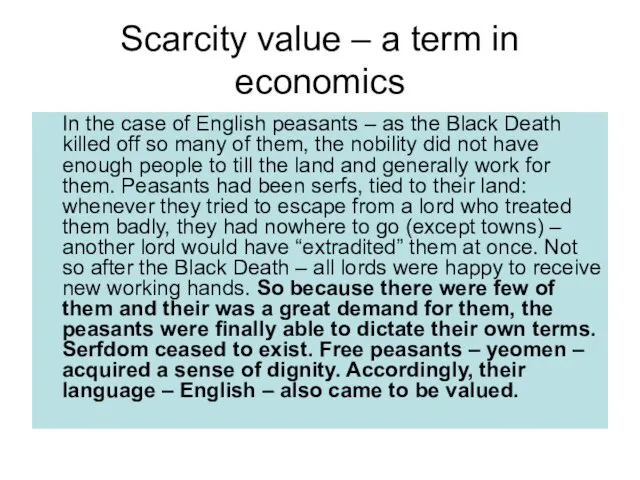

- 38. Scarcity value – a term in economics In the case of English peasants – as the

- 39. One of the many sources: Linguistic perspectives on language and education Anita K. Barry, p. 89

- 40. Other causes of the re-emergence of English The Black Death (1349) (“scarcity value”) The Hundred Years’

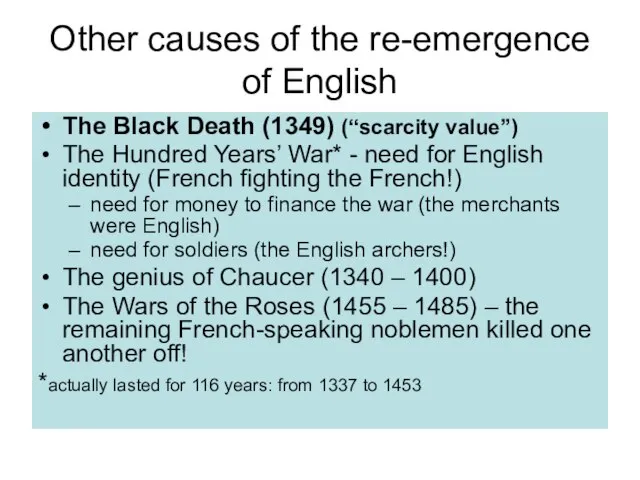

- 41. 1362 English becomes the language of Parliament and the courts of law. However, this is a

- 42. Periods of the history of English III Early Modern English 1485 – end of the Wars

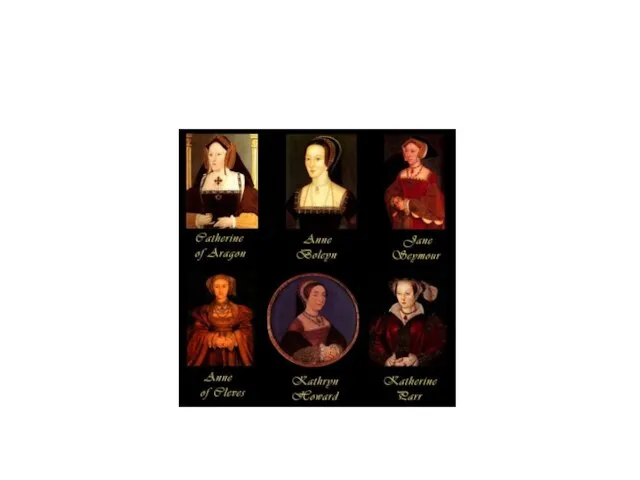

- 45. Reformation and Renaissance Two interrelated but distinct events. Unlike Protestantism on the continent, Reformation in Britain

- 46. Reformation Individual responsibility before God, no need for the mediation of the (Roman Catholic) Church Need

- 47. King James’ Bible (1611)

- 48. Lord’s prayer according to King James Version (Matthew) Our Father which art in Heaven, Hallowed be

- 49. Renaissance (started in the 14th century, reached Britain in the 16th century) Humanism, return to Ancient

- 50. Renaissance and Reformation in many ways contradictory movements (cf the Reformation iconoclasts; Renaissance flowered most in

- 51. Renaissance versus Reformation

- 52. The two events – which in Britain happened to unfold contemporaneously – however, converged in bringing

- 53. Whole-scale borrowing from Latin (as well as from Greek, Italian, Spanish) English borrowed, German resorted to

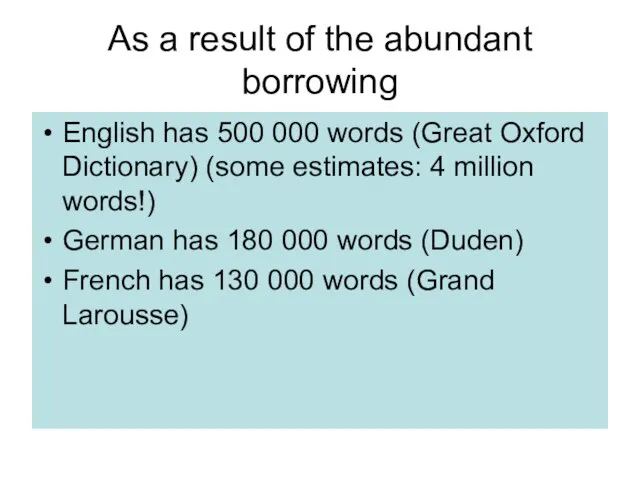

- 54. As a result of the abundant borrowing English has 500 000 words (Great Oxford Dictionary) (some

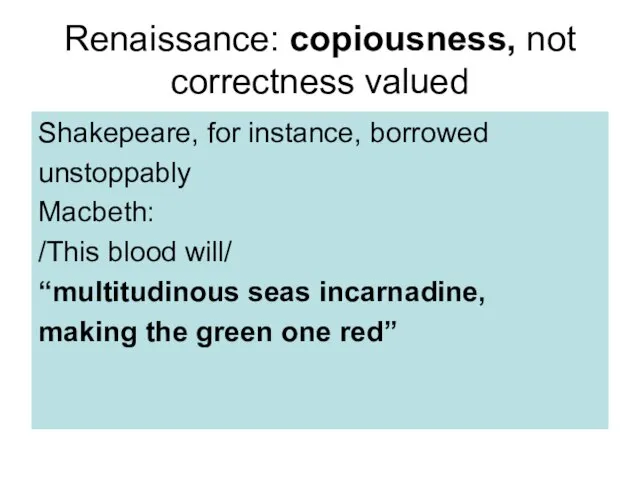

- 55. Renaissance: copiousness, not correctness valued Shakepeare, for instance, borrowed unstoppably Macbeth: /This blood will/ “multitudinous seas

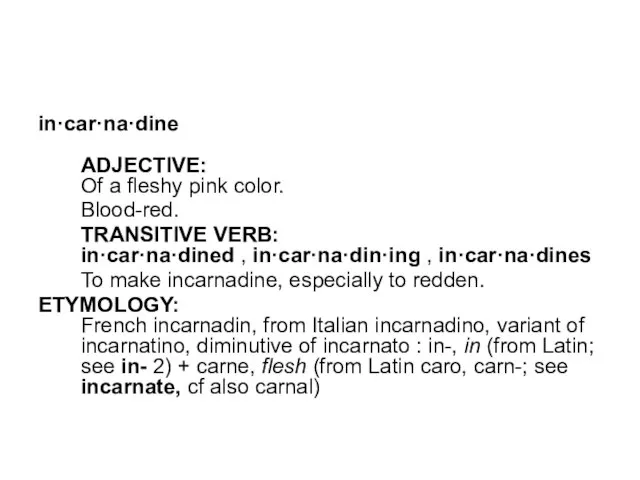

- 56. in·car·na·dine ADJECTIVE: Of a fleshy pink color. Blood-red. TRANSITIVE VERB: in·car·na·dined , in·car·na·din·ing , in·car·na·dines To

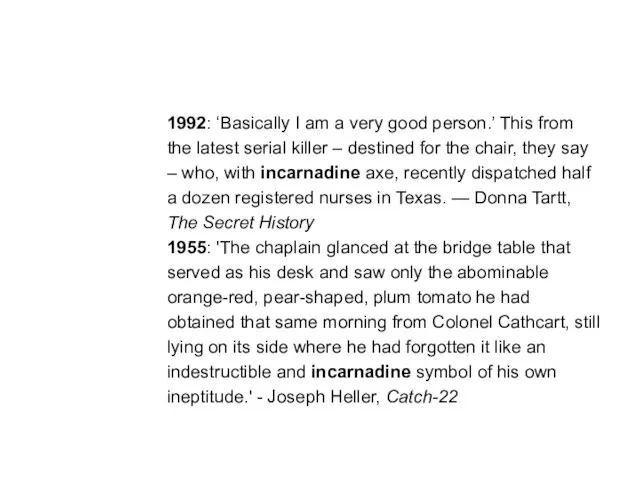

- 57. 1992: ‘Basically I am a very good person.’ This from the latest serial killer – destined

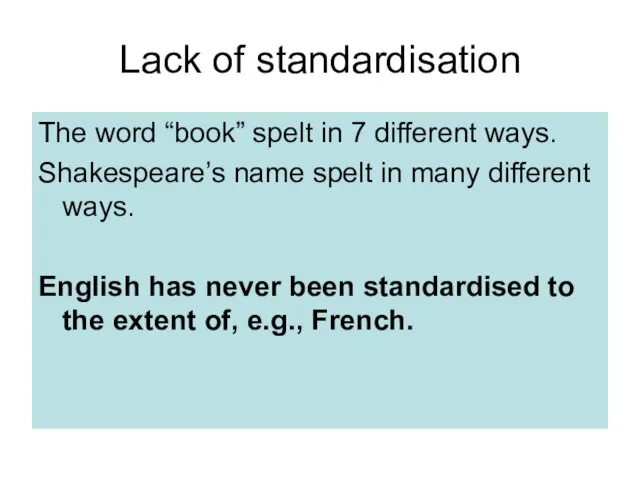

- 58. Lack of standardisation The word “book” spelt in 7 different ways. Shakespeare’s name spelt in many

- 59. The Great Vowel Shift The Great Vowel Shift was a major change in the pronunciation of

- 60. The phonetic values of the long vowels form the main difference between the pronunciation of Middle

- 61. Middle English [a:] (ā) (fronted to [æ:] and then raised to [ɛː], [e:] and in many

- 62. Causes of the Great Vowel Shift largely a mystery; possible causes (notice that all are related

- 63. Because English spelling was slowly but steadily becoming standardised in the 15th and 16th centuries, the

- 65. Скачать презентацию

![Middle English [a:] (ā) (fronted to [æ:] and then raised to [ɛː],](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/375829/slide-60.jpg)

Неизменяемые существительные

Неизменяемые существительные Экономический эффект современных Информационных Технологий

Экономический эффект современных Информационных Технологий МК Как рассчитать петли на изделие, вязанное спицами

МК Как рассчитать петли на изделие, вязанное спицами Лекція 10 УЯВА

Лекція 10 УЯВА Красные водоросли

Красные водоросли Interactive Cell Broadcast: перспективная рекламная технология

Interactive Cell Broadcast: перспективная рекламная технология Кладовая здоровья

Кладовая здоровья Путешествие вокруг света за 80 дней: реально ли?

Путешествие вокруг света за 80 дней: реально ли? Результаты деятельности КТК в области охраны окружающей среды

Результаты деятельности КТК в области охраны окружающей среды Весна в лесу

Весна в лесу Алгоритм прохождения ТПМПК

Алгоритм прохождения ТПМПК Татуировки и Здоровье

Татуировки и Здоровье Основные характеристики: Топология созвездие - многолучевая звезда с центром в Экибастузе Запад не имеет прямых связей с Севером и

Основные характеристики: Топология созвездие - многолучевая звезда с центром в Экибастузе Запад не имеет прямых связей с Севером и Проект Show Woman Russia

Проект Show Woman Russia Развитие газохимической промышленности Восточной Сибири. Перспективные точки роста.

Развитие газохимической промышленности Восточной Сибири. Перспективные точки роста. тест по информатике

тест по информатике Демографические и миграционные факторы развития Дальнего Востока России

Демографические и миграционные факторы развития Дальнего Востока России Презентация на тему Современные образовательные технологии в учебно-воспитательном процессе

Презентация на тему Современные образовательные технологии в учебно-воспитательном процессе Технология проведения тренировочных занятий по видам спорта в дистанционном формате

Технология проведения тренировочных занятий по видам спорта в дистанционном формате Структура проекта

Структура проекта Аудит и стратегия

Аудит и стратегия Контрольно-оценочная деятельность

Контрольно-оценочная деятельность Продюсерский центр Эскадрон

Продюсерский центр Эскадрон Гуляй по улицам с умом

Гуляй по улицам с умом К 140-летию со дня рождения Народной сказительницы Мордовии. Беззубова Фекла Игнатьевна

К 140-летию со дня рождения Народной сказительницы Мордовии. Беззубова Фекла Игнатьевна ШКОЛА №71:

ШКОЛА №71: Частица

Частица д.м.н., проф. М.К. Соболева Оценка качества препаратов для терапии гемофилии АПлазматические и рекомбинантные факторы свертывания

д.м.н., проф. М.К. Соболева Оценка качества препаратов для терапии гемофилии АПлазматические и рекомбинантные факторы свертывания