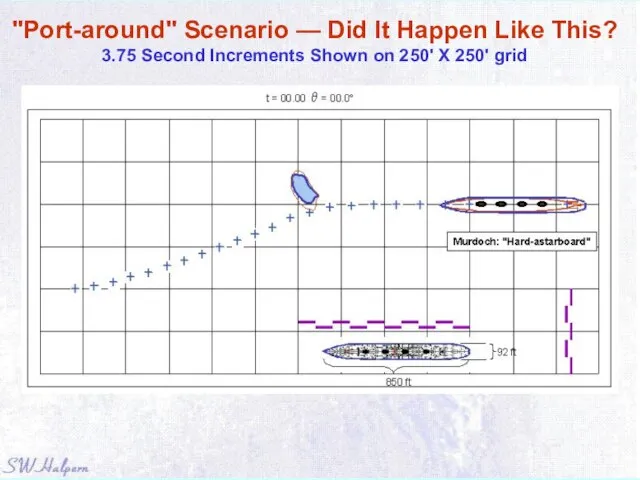

minute and a half [after the collision]. They [then] went slow astern ... about a minute and a half [later for] about two minutes."

Greaser Thomas Ranger: "We turned round and looked into the engine room and saw the turbine engine was stopped...There are two arms [that] come up as the turbine engine stops... [that was] about two minutes afterwards...[after the jar.]"

1st Class Passenger Henry Stengel: "As I woke up I heard a slight crash. I paid no attention to it until I heard the engines stop...[They were stopped] I should say two or three minutes, and then they started again just slightly; just started to move again. I do not know why; whether they were backing off, or not."

1st Class Passenger George Rheims: "I did not notice that the engines were stopped right away; they were not stopped right away; of that I am positive.

[I felt a change with reference to the engines] a few minutes after the shock, possibly two or three minutes; might have been less."

2nd Class Passenger Lawrence Beesley: "There came what seemed to me nothing more than an extra heave of the engines and a more than usually obvious dancing motion of the mattress... and presently the same thing repeated with about the same intensity...I continued my reading...But in a few moments I felt the engines slow and stop."

The engines did not stop nor reverse until some short amount of time after the ship struck the iceberg.

Презентация на тему Генетика пола. Наследование, сцепленное с полом

Презентация на тему Генетика пола. Наследование, сцепленное с полом Переход к предоставлению услуги «Прием органами опеки и попечительства документов от лиц, желающих установить опеку (попечительс

Переход к предоставлению услуги «Прием органами опеки и попечительства документов от лиц, желающих установить опеку (попечительс Как работать с YouTube?

Как работать с YouTube? Инвестиции в номерной фонд апарт-отеля

Инвестиции в номерной фонд апарт-отеля ПРОМЫШЛЕННЫЕ ЧАСТОТНО-РЕГУЛИРУЕМЫЕ ПРИВОДЫ СРЕДНЕГО НАПРЯЖЕНИЯ

ПРОМЫШЛЕННЫЕ ЧАСТОТНО-РЕГУЛИРУЕМЫЕ ПРИВОДЫ СРЕДНЕГО НАПРЯЖЕНИЯ SiSi linea benessere

SiSi linea benessere Оружие Победы (танки лёгкие)

Оружие Победы (танки лёгкие) Иконография образа Пресвятой Богородицы (Часть 1)

Иконография образа Пресвятой Богородицы (Часть 1) Презентация на тему Взаимное расположение графиков линейной функции Математика 7 класс

Презентация на тему Взаимное расположение графиков линейной функции Математика 7 класс Ағзаларды клондау

Ағзаларды клондау Психотерапия кризисных состояний, невротических расстройств и психосоматических заболеваний

Психотерапия кризисных состояний, невротических расстройств и психосоматических заболеваний Завод КТтрон. Производство материалов для ремонта, усиления, защиты строительных конструкций

Завод КТтрон. Производство материалов для ремонта, усиления, защиты строительных конструкций Defining relative clauses

Defining relative clauses  Прохождение учебной практики в учреждении образования Минский государственный профессионально-технический колледж строителей

Прохождение учебной практики в учреждении образования Минский государственный профессионально-технический колледж строителей Основы знания товара. Напольные покрытия

Основы знания товара. Напольные покрытия ПРОИЗВОЛЬНЫЕ ДВИЖЕНИЯ И ДЕЙСТВИЯ (ПРАКСИС)

ПРОИЗВОЛЬНЫЕ ДВИЖЕНИЯ И ДЕЙСТВИЯ (ПРАКСИС)  Раннефеодальная монархия Англия

Раннефеодальная монархия Англия  Инновации в образовании Сахалинской области

Инновации в образовании Сахалинской области Нормативно-правовое обеспечение деятельности частного образовательного учреждения на территории МО Котлас

Нормативно-правовое обеспечение деятельности частного образовательного учреждения на территории МО Котлас Производительность систем на основе RDBMS ORACLE

Производительность систем на основе RDBMS ORACLE Поговорим о портфолио выпускника

Поговорим о портфолио выпускника «Пеликан спешит на помощь»

«Пеликан спешит на помощь» САМОРЕГУЛИРОВАНИЕ в области обслуживания, экспертизы, проектирования и изготовления оборудования, работающего под давлением и г

САМОРЕГУЛИРОВАНИЕ в области обслуживания, экспертизы, проектирования и изготовления оборудования, работающего под давлением и г Сдаем отчет в Росфинмониторинг о проверке клиентов за период с 01.05.2021 по 27.06.2021 ФЭС версии 1.4

Сдаем отчет в Росфинмониторинг о проверке клиентов за период с 01.05.2021 по 27.06.2021 ФЭС версии 1.4 Техника Киригами

Техника Киригами Час общения. Встреча в клубе "Почемучек"

Час общения. Встреча в клубе "Почемучек" Новые(неологизмы), исконно русские и заимствованные слова Составила

Новые(неологизмы), исконно русские и заимствованные слова Составила  ИНВЕСТИЦИОННЫЙ КЛУБ ЗОЛОТАЯ ЛИГА

ИНВЕСТИЦИОННЫЙ КЛУБ ЗОЛОТАЯ ЛИГА