Слайд 2Multimodality is the application of multiple literacies within one medium. For example, understanding

a televised weather forecast (medium) involves understanding spoken language, written language, weather specific language (such as temperature scales), geography, and symbols (clouds, sun, rain, etc.). Multiple literacies or "modes" contribute to an audience's understanding of a composition. Everything from the placement of images to the organization of the content to the method of delivery creates meaning. This is the result of a shift from isolated text being relied on as the primary source of communication, to the image being utilized more frequently in the digital age. Multimodality describes communication practices in terms of the textual, aural, linguistic, spatial, and visual resources used to compose messages.

Слайд 3Eija Ventola and Martin Kaltenbacher observe, although multimodality has long been ignored

by scholars with an interest in reinforcing the boundaries of disciplines and research fields, it has "been omnipresent in most of the communicative contexts in which humans engage" (2004:1).

Слайд 4HISTORY

Multimodality (as a phenomenon) has received increasingly theoretical characterizations throughout the

history of writing. Indeed, the phenomenon has been studied at least since the 4th century BC, when classical rhetoricians alluded to it with their emphasis on voice, gesture, and expressions in public speaking. However, the term was not defined with significance until the 20th century. During this time, an exponential rise in technology created many new modes of presentation. Since then, multimodality has become standard in the 21st century, applying to various network-based forms such as art, literature, social media and advertising.

Слайд 5MULTIMODALITY & MODES

Multimodality is typically defined from one of two perspectives: it

can be described either as the coexistence of multiple modes within a particular context or as the process of decoding the coexisting modes from a viewer’s or a reader’s standpoint (e.g., Everett, 2015, p. 3). The latter emphasizes that coexisting modes do not actually interact unless they are being interpreted by someone; multimodality is understood as being the interaction of modes in the cognitive system of the viewer or the reader.

Слайд 6In order to understand either of these definitions, we must reflect on

what we mean by mode. Multimodal studies typically proposes that verbal language constitutes a mode (for a discussion of whether spoken language and written language can be understood as separate modes.

Gunther Kress's scholarship on multimodality is canonical within social semiotic approaches and has a considerable influence in many other approaches as well (writing studies). Kress defines mode in two ways.

In the first, a mode “is a socially and culturally shaped resource for making meaning. Image, writing, layout, speech, moving images are examples of different modes.”

In the second, “semiotic modes, similarly, are shaped by both the intrinsic characteristics and potentialities of the medium and by the requirements, histories and values of societies and their cultures.”

Слайд 7In Kress's theory, “mode is meaningful: it is shaped by and carries

the ‘deep’ ontological and historical/social orientations of a society and its cultures with it into every sign. Mode names the material resources shaped in often long histories of social endeavor.” Modes shape and are shaped by the systems in which they participate. Modes may aggregate into multimodal ensembles, shaped over time into familiar cultural forms, a good example being film, which combines visual modes, modes of dramatic action and speech, music and other sounds.

Слайд 8In social semiotic accounts medium is the substance in which meaning is realized and

through which it becomes available to others. Mediums include video, image, text, audio, etc. Socially, medium includes semiotic, sociocultural, and technological practices such as film, newspaper, a billboard, radio, television, theater, a classroom, etc. Multimodality makes use of the electronic medium by creating digital modes with the interlacing of image, writing, layout, speech, and video. Mediums have become modes of delivery that take the current and future contexts into consideration. Accounts in media studies overlap with these concerns, often emphasizing more the value of media as social institutions for distributing particular kinds of communications.

Слайд 9The non-verbal mode that has so far sparked the most research interest

in multimodally oriented translation research is probably the still image. The role of images in translation has been examined, for instance, in print advertisements, children’s picture books, comics and illustrated technical texts. Naturally, audiovisual translation is also an area of research where it is extremely interesting to consider the functions of modes and the overall modal configuration of a multimodal text. In filmic AD, for instance, visually perceived information is converted into an oral verbal form. In dubbing, the translation needs to fit into strict limitations posed by the other modes of the source text (ST; for instance, visual synchrony). In subtitling, the translation is presented as an additional mode—written text—which competes for the viewer’s visual attention.

Слайд 10TYPOGRAPHY

Warde argues that "[t]he most important thing about printing is that it

![TYPOGRAPHY Warde argues that "[t]he most important thing about printing is that](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/964135/slide-9.jpg)

conveys thought, ideas, images, from one mind to other minds. [...] Type well used is invisible as type, just as the perfect talking voice is the unnoticed vehicle for the translation of words, ideas" (1955: 13). Warde makes clear that she also sees typography as a conduit, by which "the mental eye focuses through type and not upon it" (1955: 16).

Слайд 11Warde’s words echo Lawrence Venuti’s discussion of the strategy of fluency (1995)

as a way to de-emphasise the text’s translated status. To date, typeface choice and other printing decisions have not been taken much into account by scholars of translation. This is perhaps a pity, because typography has, at different times and in different media, been quite active as a translation issue. The issue of the ideal typeface for subtitles, for example, has long been discussed in the industry; sans serif fonts are generally preferred as being easier to read (Diaz Cintas and Remael 2007: 84). Media consumers may have strong opinions about the adequacy of particular typefaces, colours, and so on; some fans draw a distinction, for instance, between the 'ugliness’ of player-generated subtitles for films on DVD and the elegance of laser-engraved theatrical subtitles.

Слайд 12In sixteenth-century Germany Georg Rorer, who supervised the printing of the Wittenberg

editions of Martin Luther’s translation of the Bible, developed typographical 'aids’ for the reader in the form of roman typeface in certain words. The idea (and we must remember the Reformation context in which this was taking place) was that roman typeface was used for negatively connoted words, while positively connoted words were presented exclusively in gothic (Flood 1993:133-135).

Слайд 13NEW MEDIA, NEW TOOLS

KATHARINA REISS’S TEXT TYPOLOGY:

Initial classification (1980s): “audio-medial function of

language is supplementary to the:

informative,

operative

expressive functions.

Later position (2000): multimedial texts must be considered a “hyper-type” which could in turn, be:

informative,

operative

expressive in function.

Слайд 14Mary Snell-Hornby has suggested that we can define four different genres of

multimodal text (2009: 44, some emphasis added):

- multimedial texts (in English usually called audiovisual, but not to be confused with ''multimedia’’ in its loose everyday usage) are conveyed by technical and/or electronic media involving both sight and sound (e.g. material for film or television, sub-/surtitling);

- multimodal texts involve different modes of verbal and nonverbal expression, comprising both sight and sound, as in drama and opera;

- multisemiotic texts use different graphic sign systems, verbal and nonverbal (e.g. comics or advertising brochures);

- audiomedial texts are those written to be spoken (e.g. political speeches).

Слайд 15As Littau (2011) has persuasively argued, with changing media technologies (manuscript, print,

changes in paper quality and bookbinding; web-based texts and hyperlinking) come changing theories of translation. It makes sense then that the saturated multimodality of many texts today would require both a new, or at least a rethought, critical and analytical toolbox, and potentially also new approaches to translation. Rick ledema has argued that multimodality "provides the means to describe a practice or representation in all its semiotic complexity and richness" (2003: 39).

Слайд 16

AGENCIES IN MULTIMODALITY

In-flight magazines: publishers, editors, sub-editors, copywriters, translators, graphic designers.

Film production:

directors, censors, translators, distribution companies.

NEW PROFESSIONS DERIVATIVE OF TRANSLATORS:

Localizer adapts a product or service into the language of any region or country. Language localization aside from the translation of written text could include: multimedia and video content, voiceovers and audio, websites, video games, software

Transcreator takes a concept in one language and completely recreates it in another language; applied to the marketing of an idea, product or service for international audiences.

Слайд 17WORD & IMAGE

Paratexts – those liminal devices and conventions, both within and

outside the book, that form part of the complex mediation between book, author, publisher and reader: titles, forewords, epigraphs, illustrations and publisher jacket copy are part of a book’s private and public history (G. Genette. Paratext: Theshold of Interpretation (1997);

Keith Harvey (2003) supplements Genette’s notion of paratext with his own notion of “bindings”: specifically, the outward presentation of texts in the form of book covers and blurds.

The notion of multimodality puts in question Genette’s notion of paratext, in some texts all semiotic notes are of equal importance, word and image are inseparable.

Слайд 18The very notion of multimodality puts in question Genette's notion of paratext,

with its distinction between what is 'text' and what is on the fringe of that text. With many texts we have an intuitive sense that certain semiotic modes stand in an ancillary relation to the text, with a framing function; thus the relation between images and written text in comics seems more 'integrated,' more essential, than the relationships between images and written text on, say, a book cover or in an illustrated story for children. We can imagine the book cover or the children's book with their images excised, or replaced; we cannot imagine the comic without its essential combination of text and image.

Слайд 19Mary Elizabeth Leighton and Lisa Surridge point out that "the material form

of a text always signifies," quoting Jerome McGann's observation that "apparitions of text, its paratexts, bibliographical codes and all visual features [...] are as important in the text's signifying programs as the linguistic elements" (Leighton and Surridge 2008:65). Leighton and Surridge's study of illustrated serial fiction in the Victorian period persuasively demonstrates how the location of illustrations within the text interacted with the serial presentation of the text in crucial ways. Many of these texts are now read in unillustrated editions. Leighton and Surridge argue that the illustrations were not merely ancillary, but in fact constitutive of plot, and that reading in editions which lack these illustrations leads to readers "failing to generate the visual knowledge bank that would have informed and guided the interpretive strategies of Victorian readers" (2008: 97).

Слайд 20MULTIMODALITY IN AUDIO-VISUAL TRANSLATION

Maria Tymoczko (2007, pp. 83-90) has proposed the idea

of a cluster concept as a way to make sense of all translation in an inclusive way. In her words, translation “cannot [simply be] defined in terms of necessary and sufficient features” (Tymoczko, 2007, p. 85). Translations cannot be distinguished from other products or phenomena by some characteristic that all translations would have in common, but they do have “partial and overlapping similarities” which allow us to use and understand the concept of translation (Tymoczko, 2007, p. 85). Similarly, Luis Pdrez-Gonzalez (2014a, pp. 141-142) points out that even the field of audiovisual translation on its own is so diverse that it requires multiple definitions, and he consequently endorses a flexible theoretical understanding of translation as a cluster concept.

Слайд 21In fact, all multimodal translations must take non-verbal modes into account to

some extent, and they may introduce new challenges to the translator’s task, such as modifying visual information or introducing shifts in the translation of the verbal content so as to remain consistent with the non-verbal modes. The field of multimodal translation therefore inherently encompasses many special or marginal cases of translation.

Слайд 22 According to Matkivska, while audiovisual translation involves rendering verbal components of

video, the main feature is synchronizing verbal and nonverbal components. Audio-visual translations include media, multi-medial, multimodal, and screen translations, they mainly include rendering verbal messages into visual and auditory messages and vice versa with the help of gestural and digital images. Matkivska singled out G. Gottlieb`s categorization of four main channels of information that must be taken into account while translating:

(1) verbal audio channels;

(2) nonverbal audio channels;

(3) verbal and visual channels;

(4) nonverbal visual channels.

Слайд 23ACCESSIBILITY

One of the major fields of multimodal research in translation studies

has been that of accessibility, particularly the accessibility of multi-medial experiences (e.g. museums — Soler Gallego and Jimenez Hurtado in this issue) and entertainment products, e.g. films (Romero Fresco, Maszerowska in this issue), television (Cambra in this issue) and live performing arts (Oncins et al. in this issue).

By definition, the multimodality of these texts places specific demands on the translator, but also creates a need for certain forms of access translation, in the form of audiodescription for spectators who are blind or partially sighted, as well as subtitles for spectators who have difficulty in hearing.

Слайд 24MULTIMODALITY AS CHALLENGE AND RESOURCE

In subtitling, the multimodality of the audiovisual text

is both a challenge and a resource for subtitlers. The image may impose severe challenges on the translator, e.g. through instances of verbal/visual puns, but through verbal/visual redundancy the other modes of the audiovisual text can also provide sufficient context to make certain verbal elements redundant, and thus make it easier to condense the text.

Слайд 25INTERDISCIPLINARITY IN MULTIMODAL TRANSLATION STUDIES

As is the case with Translation Studies generally,

it is impossible to delineate a single, coherent methodological framework for multimodal translation studies. In other words, both Translation Studies and multimodal translation studies are also cluster concepts in a methodological sense. Different types of multimodal translation may form interdisciplinary connections in different directions—audiovisual translation with film studies, technical translation with technical communication and videogames with human computer interaction.

Слайд 26Let's revise

1. What is multimodality?

Слайд 272.The phenomenon of multimodality has been studied since

the 5th century BC

the 4th

century BC

the 20th century

Слайд 28The phenomenon of multimodality has been studied since

the 5th century BC

the 4th

century BC

the 20th century

Слайд 293. What is mode according to Gunter Kress?

Слайд 30According to Gunther Kress, a mode is a resource for meaning-making, one

used for representation and communication.

Слайд 314. Four genres of multimodal text according to Mary Snell-Hornby are...

Слайд 321. multimedial texts

2. multimodal texts

3. multisemiotic texts

4. audiomedial texts

Слайд 335.Who defines modes in two ways and states that “mode is meaningful”?

a)Gunther

Kress

b)Theo van Leeuwen

c)John A. Bateman

Слайд 34a)Gunther Kress

b)Theo van Leeuwen

c)John A. Bateman

Слайд 356. Who supplements Genette's notion of paratext with his own notion of

'bindings'?

a)Lisa Surridge

b)Keith Harvey

c)Mary Elizabeth Leighton

Слайд 36

a)Lisa Surridge

b)Keith Harvey

c)Mary Elizabeth Leighton

Слайд 377. Why can multimodality be both a challenge and a resource for

translators?

![TYPOGRAPHY Warde argues that "[t]he most important thing about printing is that](/_ipx/f_webp&q_80&fit_contain&s_1440x1080/imagesDir/jpg/964135/slide-9.jpg)

Смысловые и вспомогательные глаголы

Смысловые и вспомогательные глаголы Modal verbs for speculation

Modal verbs for speculation Christmas is Christmas is a wonderful holiday!

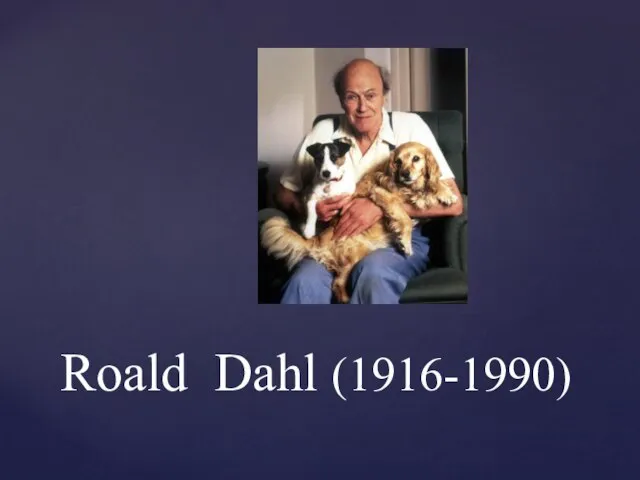

Christmas is Christmas is a wonderful holiday! Roald Dahl (1916-1990)

Roald Dahl (1916-1990) Artikles a an the

Artikles a an the Euro-trip

Euro-trip English Language

English Language Презентация на тему ОТРИЦАТЕЛЬНОЕ И ВОПРОСИТЕЛЬНОЕ ПРЕДЛОЖЕНИЕ В PAST SIMPLE

Презентация на тему ОТРИЦАТЕЛЬНОЕ И ВОПРОСИТЕЛЬНОЕ ПРЕДЛОЖЕНИЕ В PAST SIMPLE  English is fun to learn

English is fun to learn I have a toy

I have a toy Zoo vet

Zoo vet Was wollen wir in den ferien machen

Was wollen wir in den ferien machen Life without gadgets

Life without gadgets Фразовые глаголы

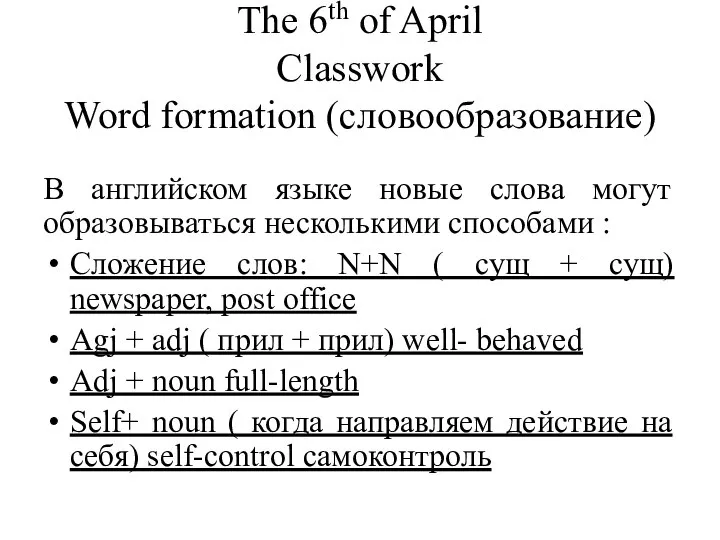

Фразовые глаголы Сложение слов: N+N (сущ + сущ) newspaper, post office

Сложение слов: N+N (сущ + сущ) newspaper, post office Time expressions for present continuous

Time expressions for present continuous Verb: noun (adjective), stress

Verb: noun (adjective), stress Collocations

Collocations Grammar and vocabulary (грамматика и лексика)

Grammar and vocabulary (грамматика и лексика) The subject of phonetics of the english language

The subject of phonetics of the english language Kinds Of Food

Kinds Of Food Project template

Project template Henry VI

Henry VI It has 4 legs

It has 4 legs Идиомы и идиоматические выражения

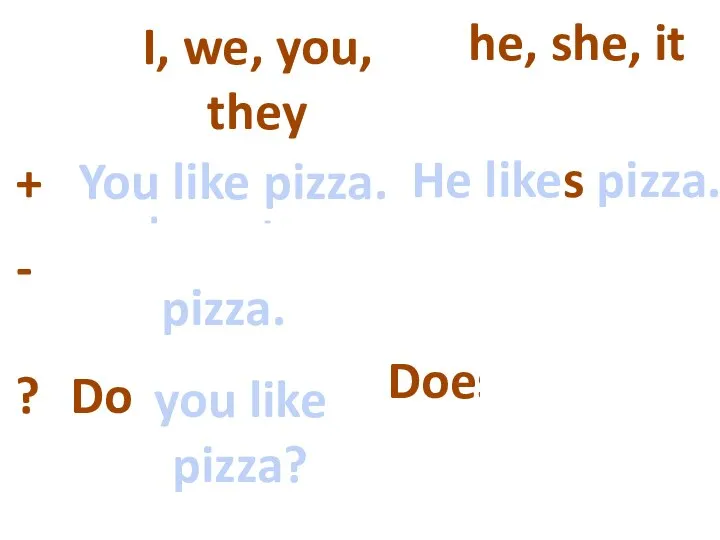

Идиомы и идиоматические выражения Present simple

Present simple Вебинар по организации проверки ВПР по английскому языку

Вебинар по организации проверки ВПР по английскому языку Тренажер по английскому языку. Глаголы движения. Животные

Тренажер по английскому языку. Глаголы движения. Животные