- Главная

- Биология

- Rescue of the senescence phenotype of AD MSCs by autophagy activation in 3D spheroids

Содержание

- 2. Human MSCs (hMSCs) are cells capable of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation into various tissues of mesodermal

- 3. The term senescence was applied to cells that ceased to divide in culture, based on the

- 4. Expression levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3B are significantly decreased during the replicative senescence of MSCs, leading

- 5. The hallmark of cellular senescence is an inability to progress through the cell cycle. G1 cell

- 6. Lozano-Torres B., et al., 2019. The chemistry of senescence . NATuRe RevIewS volume 3; 427 Drugs

- 7. The senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) - is detectable in most senescent cells. However, it is also induced

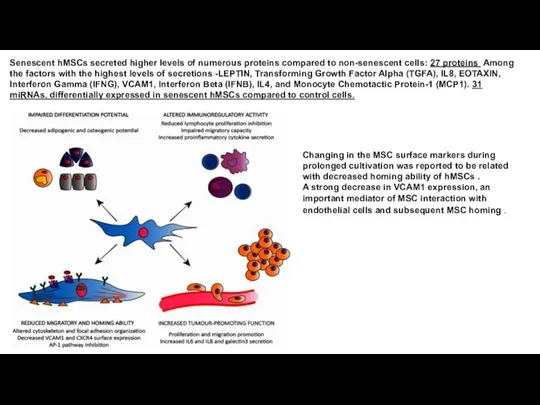

- 8. Senescent hMSCs secreted higher levels of numerous proteins compared to non-senescent cells: 27 proteins Among the

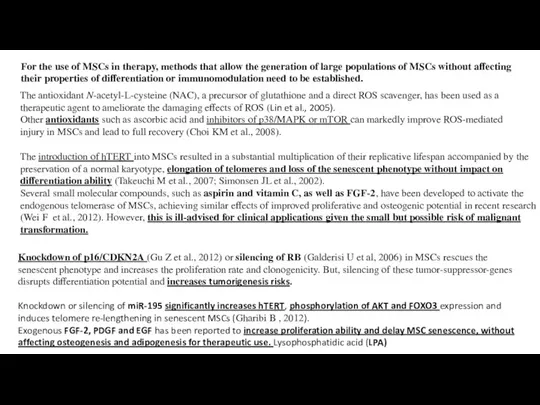

- 9. For the use of MSCs in therapy, methods that allow the generation of large populations of

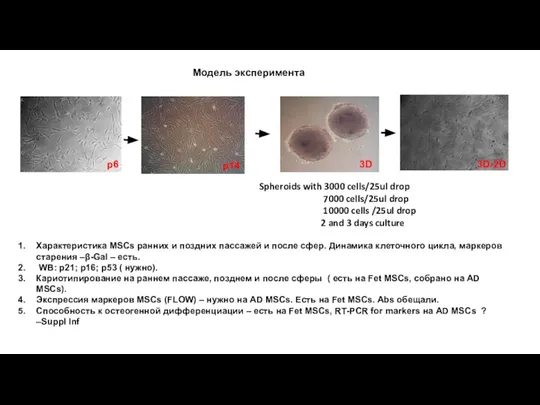

- 10. Модель эксперимента p6 3D 3D-2D Характеристика MSCs ранних и поздних пассажей и после сфер. Динамика клеточного

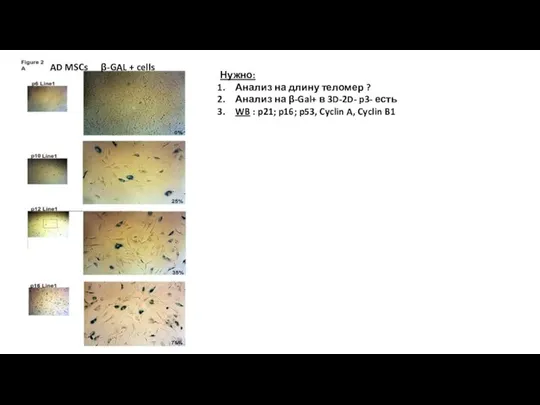

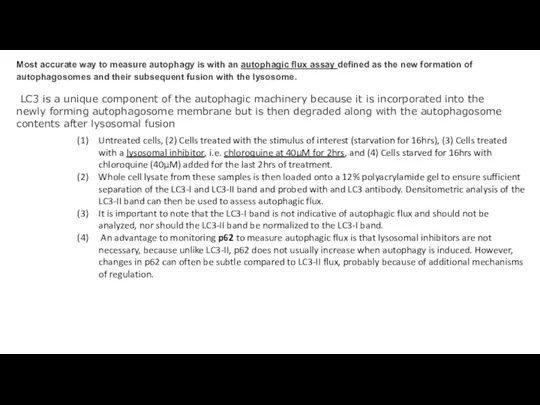

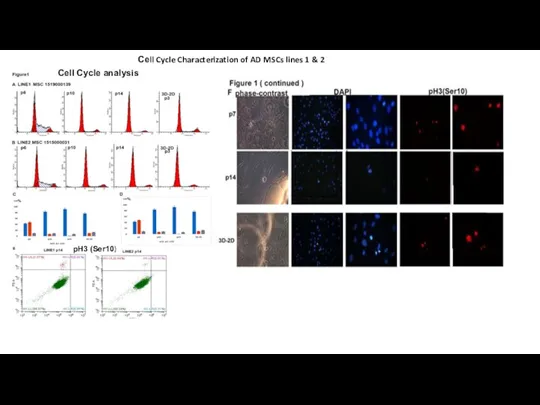

- 11. Сеll Cycle Characterization of AD MSCs lines 1 & 2 Cell Cycle analysis pH3 (Ser10)

- 12. %

- 13. Нужно: Анализ на длину теломер ? Анализ на β-Gal+ в 3D-2D- p3- есть WB : p21;

- 14. КАРИОТИПИРОВАНИЕ Fet MSCs p7 3D-2D /p3 Кариотипирование AD MSCs -+

- 15. Остеогенная дифференцировка Fet MSCs Окрашивание на щелочную фосфатазу p6 3D → 2D Окрашивание по Van Kossa

- 16. Автофагоцитоз (реакция на кислую фосфатазу по Гомори ) Fet MSCs p6 p12 shp 3D-2D Активность AcPase

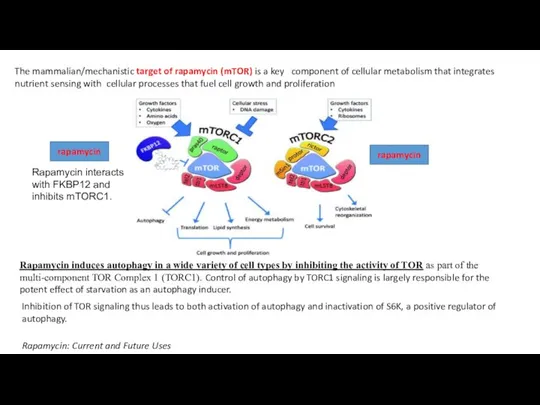

- 17. p12 p230 trans-Golgi-coil protein p5 3D-2D shp p230/golgin-245 is a trans-Golgi coiled-coil protein that is known

- 18. Происходит ли омоложение популяции в сфероидах за счет усиленного аутофагоцитоза ? Regulatory components for autophagy induction

- 19. The mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key component of cellular metabolism that integrates nutrient

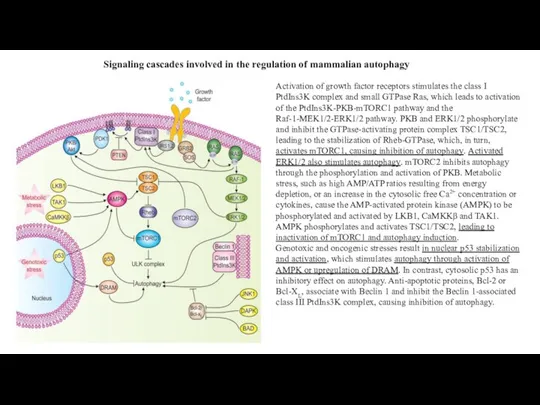

- 20. Signaling cascades involved in the regulation of mammalian autophagy Activation of growth factor receptors stimulates the

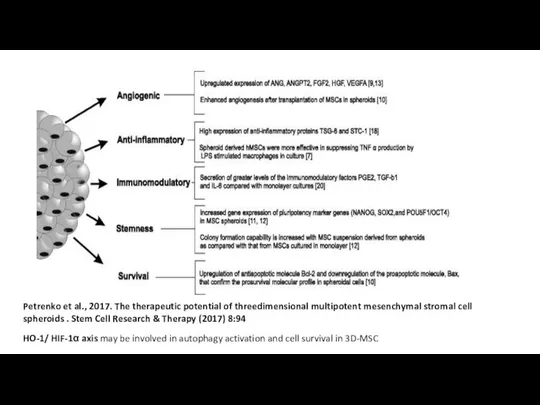

- 21. Decreased Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in 3D-mesenhcymal Stem Cell Spheroids Leads to Increased Therapeutic Efficacy

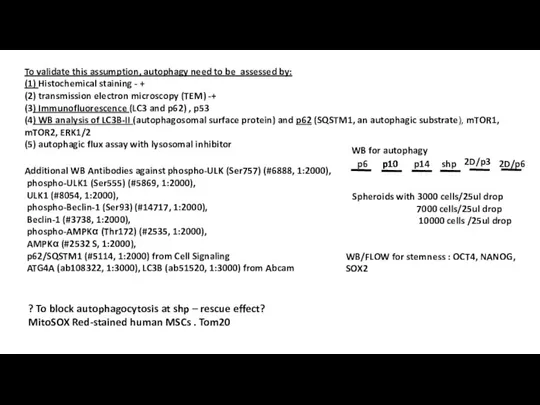

- 22. PI3K/AKT and MAPK inhibit autophagy by regulating mTOR signaling pathway, p53 serves the opposite effect. AMPK

- 23. Petrenko et al., 2017. The therapeutic potential of threedimensional multipotent mesenchymal stromal cell spheroids . Stem

- 24. To validate this assumption, autophagy need to be assessed by: (1) Histochemical staining - + (2)

- 25. Most accurate way to measure autophagy is with an autophagic flux assay defined as the new

- 26. Одним из специфических свойств МСК является колониеобразование. При этом установлено, что только около 30% колониеобразующих мезенхимальных

- 28. Скачать презентацию

Слайд 2Human MSCs (hMSCs) are cells capable of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation into

Human MSCs (hMSCs) are cells capable of self-renewal and multi-lineage differentiation into

MSCs have been broadly applied in the treatment of various diseases, including graft-versus-host disease (GVHD), Crohn's disease (CD), diabetes mellitus (DM), multiple sclerosis (MS), myocardial infarction (MI), liver failure, and rejection after liver transplant.

Upon isolation, hMSCs are characterized by their capability to develop as fibroblast colony-forming-units, and differentiate into osteocytes, chondrocytes, and adipocytes.

hMSCs are positive for CD73, CD90, CD105, СD106, CD29, CD166, and negative for CD11b, CD14, CD34, CD45, HLA-DR, CD79α and CD19.

Cultured primary cells do not grown infinitely, but undergo only a limited number of cell division, in a process called cellular senescence. Cell therapy protocols generally require hundreds of million hMSCs per treatment and, consequently, these cells need to be expanded in vitro for about 10 weeks before implantation. Notably, patient’s clinical history, age, and genetic makeup strongly influence the length of this expansion period and the quality of the obtained cells. Aged MSCs generally perform less well than their younger counterparts in various disease models and mounting evidence strongly suggests that cellular senescence contribute to aging and age-related diseases.

It would, thus, be of great significance to monitor the occurrence of a senescent phenotype in hMSCs addressed to clinical uses and to evaluate the functional consequences of senescence in hMSCs which could affect their clinical therapeutic potential, taking into account their paracrine effects, immunomodulatory activity, differentiation potential, and cell migration ability.

The function of MSCs is known to decline with age, a process that may be implicated in the loss of maintenance of tissue homeostasis leading to organ failure and diseases of aging

Слайд 3The term senescence was applied to cells that ceased to divide in

The term senescence was applied to cells that ceased to divide in

Telomere shortening provided the first molecular explanation for why many cells cease to divide in culture. Dysfunctional telomeres trigger senescence through the p53 pathway.

This response is often termed telomere-initiated cellular senescence. Some cells undergo replicative senescence independently of telomere shortening.

Resistance to apoptosis might partly explain why senescent cells are so stable in culture. This attribute might also explain why the number of senescent cells increases with age.

Changes in cell cycle inhibitors: p21Cip1 and p16InK4a. These CDKIs are components of tumour suppressor pathways

that are governed by the p53 and retinoblastoma pRB proteins.

New markers in Oncogene induced senescence: DEC1 (differentiated embryo chondrocyte expressed1), p15 (a CDKI) and DCR2 (decoy death receptor2). The specificity and significance of these proteins for senescent cells are not yet clear, but they are promising additional markers.

Dramatic structural changes of chromatin in senescent cells- Lamin B1. Presence of certain heterochromatin associated histone modifications (H3 lys9 methylation) and heterochromatin protein1 (Hp1)). In some cases - global heterochromatin loss, characterized by markers H3K9me3 and H3K27me3. Predominantly during OIS in vitro, heterochromatin is redistributed into 30–50 punctate DNA-dense senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF). SAHF are silent domains that co-localize with H3K9me3 and heterochromatin protein 1 (HP1) and may lock cells in a senescent state by transcriptionally repressing genes involved in cell proliferation.

MARKERS of SENESCENCE

Слайд 4Expression levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3B are significantly decreased during the replicative

Expression levels of DNMT1 and DNMT3B are significantly decreased during the replicative

In contrast, DNMT3a expression was found to be increased during replicative senescence, participating in the new methylation associated with senescence. DNMT inhibitors, such as 5-azacytidine, can upregulate p16INK4a/CDKN2A, p21CIP1/WAF1 and miRNAs targeting EZH1, and the induction of cellular senescence in MSCs

DNA methyltransferases (DNMTs)

Слайд 5The hallmark of cellular senescence is an inability to progress through the

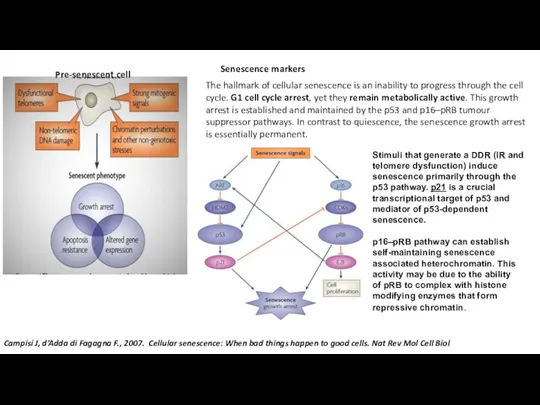

The hallmark of cellular senescence is an inability to progress through the

Senescence markers

Pre-senescent cell

Stimuli that generate a DDR (IR and telomere dysfunction) induce senescence primarily through the p53 pathway. p21 is a crucial transcriptional target of p53 and mediator of p53-dependent senescence.

Campisi J, d’Adda di Fagagna F., 2007. Cellular senescence: When bad things happen to good cells. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol

p16–pRB pathway can establish self-maintaining senescence associated heterochromatin. This activity may be due to the ability of pRB to complex with histone modifying enzymes that form repressive chromatin.

Слайд 6 Lozano-Torres B., et al., 2019. The chemistry of senescence . NATuRe RevIewS

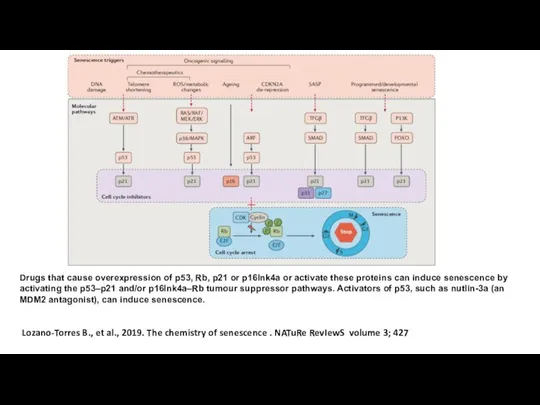

Lozano-Torres B., et al., 2019. The chemistry of senescence . NATuRe RevIewS

Drugs that cause overexpression of p53, Rb, p21 or p16Ink4a or activate these proteins can induce senescence by activating the p53–p21 and/or p16Ink4a–Rb tumour suppressor pathways. Activators of p53, such as nutlin-3a (an MDM2 antagonist), can induce senescence.

Слайд 7The senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) - is detectable in most senescent cells. However,

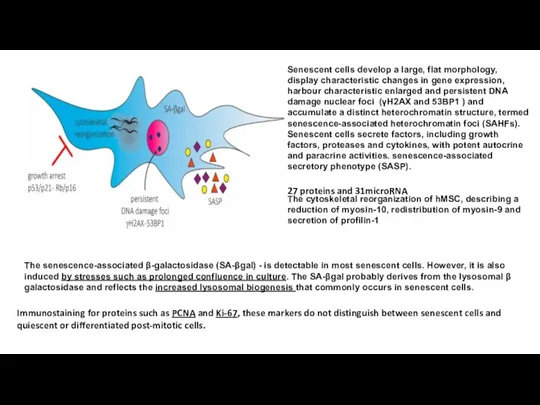

The senescence-associated β-galactosidase (SA-βgal) - is detectable in most senescent cells. However,

Senescent cells develop a large, flat morphology, display characteristic changes in gene expression, harbour characteristic enlarged and persistent DNA damage nuclear foci (γH2AX and 53BP1 ) and accumulate a distinct heterochromatin structure, termed senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHFs).

Senescent cells secrete factors, including growth factors, proteases and cytokines, with potent autocrine and paracrine activities. senescence-associated secretory phenotype (SASP).

The cytoskeletal reorganization of hMSC, describing a reduction of myosin-10, redistribution of myosin-9 and secretion of profilin-1

Immunostaining for proteins such as PCNA and Ki-67, these markers do not distinguish between senescent cells and quiescent or differentiated post-mitotic cells.

27 proteins and 31microRNA

Слайд 8Senescent hMSCs secreted higher levels of numerous proteins compared to non-senescent cells:

Senescent hMSCs secreted higher levels of numerous proteins compared to non-senescent cells:

Changing in the MSC surface markers during prolonged cultivation was reported to be related with decreased homing ability of hMSCs .

A strong decrease in VCAM1 expression, an important mediator of MSC interaction with endothelial cells and subsequent MSC homing .

Слайд 9For the use of MSCs in therapy, methods that allow the generation

For the use of MSCs in therapy, methods that allow the generation

The antioxidant N-acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC), a precursor of glutathione and a direct ROS scavenger, has been used as a therapeutic agent to ameliorate the damaging effects of ROS (Lin et al., 2005).

Other antioxidants such as ascorbic acid and inhibitors of p38/MAPK or mTOR can markedly improve ROS-mediated injury in MSCs and lead to full recovery (Choi KM et al., 2008).

The introduction of hTERT into MSCs resulted in a substantial multiplication of their replicative lifespan accompanied by the preservation of a normal karyotype, elongation of telomeres and loss of the senescent phenotype without impact on differentiation ability (Takeuchi M et al., 2007; Simonsen JL et al., 2002).

Several small molecular compounds, such as aspirin and vitamin C, as well as FGF-2, have been developed to activate the endogenous telomerase of MSCs, achieving similar effects of improved proliferative and osteogenic potential in recent research (Wei F et al., 2012). However, this is ill-advised for clinical applications given the small but possible risk of malignant transformation.

Knockdown of p16/CDKN2A (Gu Z et al., 2012) or silencing of RB (Galderisi U et al, 2006) in MSCs rescues the senescent phenotype and increases the proliferation rate and clonogenicity. But, silencing of these tumor-suppressor-genes disrupts differentiation potential and increases tumorigenesis risks.

Knockdown or silencing of miR-195 significantly increases hTERT, phosphorylation of AKT and FOXO3 expression and induces telomere re-lengthening in senescent MSCs (Gharibi B , 2012).

Exogenous FGF-2, PDGF and EGF has been reported to increase proliferation ability and delay MSC senescence, without affecting osteogenesis and adipogenesis for therapeutic use. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA)

Слайд 10Модель эксперимента

p6

3D

3D-2D

Характеристика MSCs ранних и поздних пассажей и после сфер. Динамика

Модель эксперимента

p6

3D

3D-2D

Характеристика MSCs ранних и поздних пассажей и после сфер. Динамика

WB: p21; p16; p53 ( нужно).

Кариотипирование на раннем пассаже, позднем и после сферы ( есть на Fet MSCs, собрано на AD MSCs).

Экспрессия маркеров MSCs (FLOW) – нужно на AD MSCs. Есть на Fet MSCs. Abs обещали.

Способность к остеогенной дифференциации – есть на Fet MSCs, RT-PCR for markers на AD MSCs ? –Suppl Inf

p14

Spheroids with 3000 cells/25ul drop

7000 cells/25ul drop

10000 cells /25ul drop

2 and 3 days culture

Слайд 13Нужно:

Анализ на длину теломер ?

Анализ на β-Gal+ в 3D-2D- p3- есть

WB

Нужно:

Анализ на длину теломер ?

Анализ на β-Gal+ в 3D-2D- p3- есть

WB

β-GAL + cells

AD MSCs

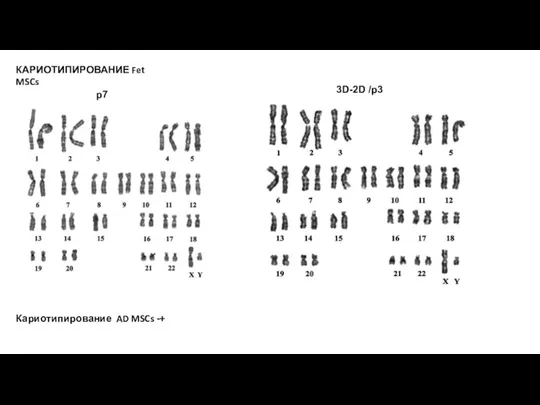

Слайд 14КАРИОТИПИРОВАНИЕ Fet MSCs

p7

3D-2D /p3

Кариотипирование AD MSCs -+

КАРИОТИПИРОВАНИЕ Fet MSCs

p7

3D-2D /p3

Кариотипирование AD MSCs -+

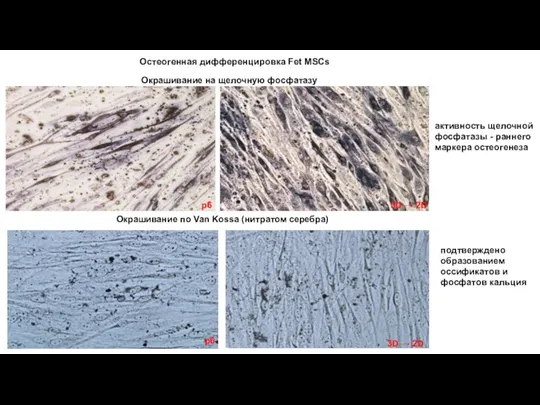

Слайд 15 Остеогенная дифференцировка Fet MSCs

Окрашивание на щелочную фосфатазу

p6

3D → 2D

Окрашивание по Van

Остеогенная дифференцировка Fet MSCs

Окрашивание на щелочную фосфатазу

p6

3D → 2D

Окрашивание по Van

3D → 2D

p6

подтверждено образованием оссификатов и фосфатов кальция

активность щелочной фосфатазы - раннего маркера остеогенеза

Слайд 16Автофагоцитоз (реакция на кислую фосфатазу по Гомори ) Fet MSCs

p6

p12

shp

3D-2D

Активность AcPase

Автофагоцитоз (реакция на кислую фосфатазу по Гомори ) Fet MSCs

p6

p12

shp

3D-2D

Активность AcPase

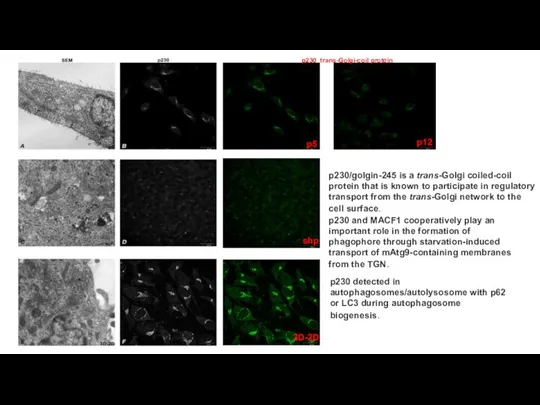

Слайд 17p12

p230 trans-Golgi-coil protein

p5

3D-2D

shp

p230/golgin-245 is a trans-Golgi coiled-coil protein that is known to

p12

p230 trans-Golgi-coil protein

p5

3D-2D

shp

p230/golgin-245 is a trans-Golgi coiled-coil protein that is known to

p230 and MACF1 cooperatively play an important role in the formation of phagophore through starvation-induced transport of mAtg9-containing membranes from the TGN.

p230 detected in autophagosomes/autolysosome with p62 or LC3 during autophagosome biogenesis.

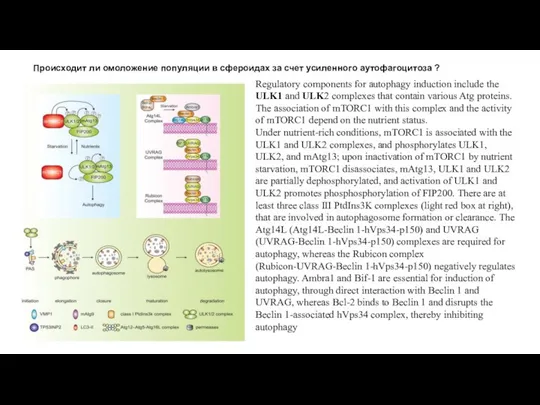

Слайд 18Происходит ли омоложение популяции в сфероидах за счет усиленного аутофагоцитоза ?

Regulatory components

Происходит ли омоложение популяции в сфероидах за счет усиленного аутофагоцитоза ?

Regulatory components

Under nutrient-rich conditions, mTORC1 is associated with the ULK1 and ULK2 complexes, and phosphorylates ULK1, ULK2, and mAtg13; upon inactivation of mTORC1 by nutrient starvation, mTORC1 disassociates, mAtg13, ULK1 and ULK2 are partially dephosphorylated, and activation of ULK1 and ULK2 promotes phosphosphorylation of FIP200. There are at least three class III PtdIns3K complexes (light red box at right), that are involved in autophagosome formation or clearance. The Atg14L (Atg14L-Beclin 1-hVps34-p150) and UVRAG (UVRAG-Beclin 1-hVps34-p150) complexes are required for autophagy, whereas the Rubicon complex (Rubicon-UVRAG-Beclin 1-hVps34-p150) negatively regulates autophagy. Ambra1 and Bif-1 are essential for induction of autophagy, through direct interaction with Beclin 1 and UVRAG, whereas Bcl-2 binds to Beclin 1 and disrupts the Beclin 1-associated hVps34 complex, thereby inhibiting autophagy

Слайд 19The mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key component of cellular metabolism that integrates

nutrient sensing with cellular processes that fuel cell growth and proliferation

rapamycin

rapamycin

Rapamycin interacts with FKBP12 and inhibits mTORC1.

Rapamycin: Current and Future

The mammalian/mechanistic target of rapamycin (mTOR) is a key component of cellular metabolism that integrates

nutrient sensing with cellular processes that fuel cell growth and proliferation

rapamycin

rapamycin

Rapamycin interacts with FKBP12 and inhibits mTORC1.

Rapamycin: Current and Future

Inhibition of TOR signaling thus leads to both activation of autophagy and inactivation of S6K, a positive regulator of autophagy.

Rapamycin induces autophagy in a wide variety of cell types by inhibiting the activity of TOR as part of the multi-component TOR Complex 1 (TORC1). Control of autophagy by TORC1 signaling is largely responsible for the potent effect of starvation as an autophagy inducer.

Слайд 20Signaling cascades involved in the regulation of mammalian autophagy

Activation of growth factor

Signaling cascades involved in the regulation of mammalian autophagy

Activation of growth factor

Genotoxic and oncogenic stresses result in nuclear p53 stabilization and activation, which stimulates autophagy through activation of AMPK or upregulation of DRAM. In contrast, cytosolic p53 has an inhibitory effect on autophagy. Anti-apoptotic proteins, Bcl-2 or Bcl-XL, associate with Beclin 1 and inhibit the Beclin 1-associated class III PtdIns3K complex, causing inhibition of autophagy.

Слайд 21Decreased Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in 3D-mesenhcymal Stem Cell Spheroids Leads

Decreased Production of Reactive Oxygen Species in 3D-mesenhcymal Stem Cell Spheroids Leads

ABSTRACT. In previous studies, 3D-MSC spheroids showed enhanced antiinflammatory effect and higher cell survival. In this study, we aimed to investigate the molecular signaling pathways responsible for the enhancement of cell viability in 3D-MSC, particularly focusing on autophagy and reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Method 3D-MSC spheroids were prepared by using hanging drop technique. Cell viability, ROS production, and autophagy activation in 3D-MSC were compared with that of 2D-cultured MSC

Results 3D-MSC showed higher cell viability, low ROS production, and upregulation in the expression of antioxidant proteins such as catalase, SOD2, and hemooxygenase-1 (HO-1). Inhibition of HO-1 by gene silencing in the 3D-MSC led to an increase in ROS production. In addition, HO-1 induction upregulated the catalase expression and attenuated ROS production in the MSC. Interesting, HO-1 induction further induced autophagy activation. Furthermore, inhibition HIF-1α resulted in HO-1 downregulation in 3D-MSC. This suggested HO-1/ HIF-1α axis may be involved in autophagy activation and cell survival in 3D-MSC. In vivo, silencing of autophagy in 3D-MSC caused decreased effectiveness of the MSC in ameliorating colitis in mice.

Conclusion The attenuation of ROS production in 3D-MSC led to an enhancement in MSC survival via the induction of autophagy. Therefore, the therapeutic effectiveness of 3D-MSC is at least, in part, mediated by autophagy induction.

Слайд 22PI3K/AKT and MAPK inhibit autophagy by regulating mTOR signaling pathway, p53 serves

PI3K/AKT and MAPK inhibit autophagy by regulating mTOR signaling pathway, p53 serves

AMPK upregulates autophagy by activating ULK1 complex. Bcl-2 inhibits autophagy by interacting with Beclin1. Rapamycin promotes the nucleation step of autophagosome, but wortmannin and 3MA inhibit this step.

CQ and Baf A1 impair the autophagic flux by inhibiting the fusion autophagosome and lysosome.

AMPK, 5′ AMP-activated protein kinase; ULK1, Serine/threonine-protein kinase ULK1;

CQ, chloroquine;

BAF, bafilomycin A1;

3MA, 3-methyladenine.

Слайд 23Petrenko et al., 2017. The therapeutic potential of threedimensional multipotent mesenchymal stromal

Petrenko et al., 2017. The therapeutic potential of threedimensional multipotent mesenchymal stromal

HO-1/ HIF-1α axis may be involved in autophagy activation and cell survival in 3D-MSC

Слайд 24To validate this assumption, autophagy need to be assessed by:

(1) Histochemical

To validate this assumption, autophagy need to be assessed by:

(1) Histochemical

(2) transmission electron microscopy (TEM) -+

(3) Immunofluorescence (LC3 and p62) , p53

(4) WB analysis of LC3B-II (autophagosomal surface protein) and p62 (SQSTM1, an autophagic substrate), mTOR1, mTOR2, ERK1/2

(5) autophagic flux assay with lysosomal inhibitor

Additional WB Antibodies against phospho-ULK (Ser757) (#6888, 1:2000),

phospho-ULK1 (Ser555) (#5869, 1:2000),

ULK1 (#8054, 1:2000),

phospho-Beclin-1 (Ser93) (#14717, 1:2000),

Beclin-1 (#3738, 1:2000),

phospho-AMPKα (Thr172) (#2535, 1:2000),

AMPKα (#2532 S, 1:2000),

p62/SQSTM1 (#5114, 1:2000) from Cell Signaling

ATG4A (ab108322, 1:3000), LC3B (ab51520, 1:3000) from Abcam

? To block autophagocytosis at shp – rescue effect? MitoSOX Red-stained human MSCs . Tom20

p10

p6

p10

p10

p14

shp

2D/p3

2D/p6

Spheroids with 3000 cells/25ul drop

7000 cells/25ul drop

10000 cells /25ul drop

WB for autophagy

WB/FLOW for stemness : OCT4, NANOG, SOX2

Слайд 25Most accurate way to measure autophagy is with an autophagic flux assay defined

Most accurate way to measure autophagy is with an autophagic flux assay defined

LC3 is a unique component of the autophagic machinery because it is incorporated into the newly forming autophagosome membrane but is then degraded along with the autophagosome contents after lysosomal fusion

Untreated cells, (2) Cells treated with the stimulus of interest (starvation for 16hrs), (3) Cells treated with a lysosomal inhibitor, i.e. chloroquine at 40μM for 2hrs, and (4) Cells starved for 16hrs with chloroquine (40μM) added for the last 2hrs of treatment.

Whole cell lysate from these samples is then loaded onto a 12% polyacrylamide gel to ensure sufficient separation of the LC3-I and LC3-II band and probed with and LC3 antibody. Densitometric analysis of the LC3-II band can then be used to assess autophagic flux.

It is important to note that the LC3-I band is not indicative of autophagic flux and should not be analyzed, nor should the LC3-II band be normalized to the LC3-I band.

An advantage to monitoring p62 to measure autophagic flux is that lysosomal inhibitors are not necessary, because unlike LC3-II, p62 does not usually increase when autophagy is induced. However, changes in p62 can often be subtle compared to LC3-II flux, probably because of additional mechanisms of regulation.

Слайд 26Одним из специфических свойств МСК является колониеобразование. При этом установлено, что только

Одним из специфических свойств МСК является колониеобразование. При этом установлено, что только

CFE assay

Тропические леса

Тропические леса Размножение

Размножение Презентация на тему Подтип Позвоночные. Рыбы – водные позвоночные животные

Презентация на тему Подтип Позвоночные. Рыбы – водные позвоночные животные  Презентация на тему Редкие виды животных и растений Пермского края

Презентация на тему Редкие виды животных и растений Пермского края  Учение В.И.вернадского о биосфере. 9 класс

Учение В.И.вернадского о биосфере. 9 класс Сколько живут растения

Сколько живут растения Лягушка. Оригами

Лягушка. Оригами Основные закономерности наследственности

Основные закономерности наследственности Отдел Папоротниковидные (тема 29)

Отдел Папоротниковидные (тема 29) Обмен веществ и превращение энергии в клетке. Пластический обмен

Обмен веществ и превращение энергии в клетке. Пластический обмен Презентация на тему Красная Книга планеты Земля

Презентация на тему Красная Книга планеты Земля  Нуклеиновые кислоты

Нуклеиновые кислоты Презентация на тему Кровь и кровеносная система

Презентация на тему Кровь и кровеносная система  Бақанас орман және жануарлар дүниесін қорғау жөніндегі мемлекеттік мекемесінің кеңсесі

Бақанас орман және жануарлар дүниесін қорғау жөніндегі мемлекеттік мекемесінің кеңсесі Презентация на тему Биогеоценоз

Презентация на тему Биогеоценоз  Пластический обмен у автотрофов

Пластический обмен у автотрофов Я і навакольны свет. Надвор’е, з’явы прыроды

Я і навакольны свет. Надвор’е, з’явы прыроды Каждое утро жизнь возобновляется

Каждое утро жизнь возобновляется Экология бактерий

Экология бактерий Пташині гнізда

Пташині гнізда Наследственная изменчивость. Комбинативная изменчивость

Наследственная изменчивость. Комбинативная изменчивость Строение и значение нервной системы

Строение и значение нервной системы Генетический код. Первичное действие гена

Генетический код. Первичное действие гена Переработка углеводсодержащего сырья

Переработка углеводсодержащего сырья Функциональная анатомия органов дыхания

Функциональная анатомия органов дыхания Рыба и рыбные товары

Рыба и рыбные товары Как живут животные

Как живут животные Роль запахов в мире животных

Роль запахов в мире животных