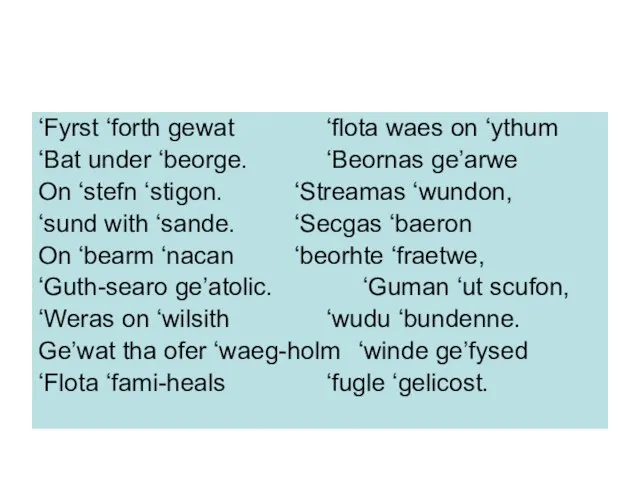

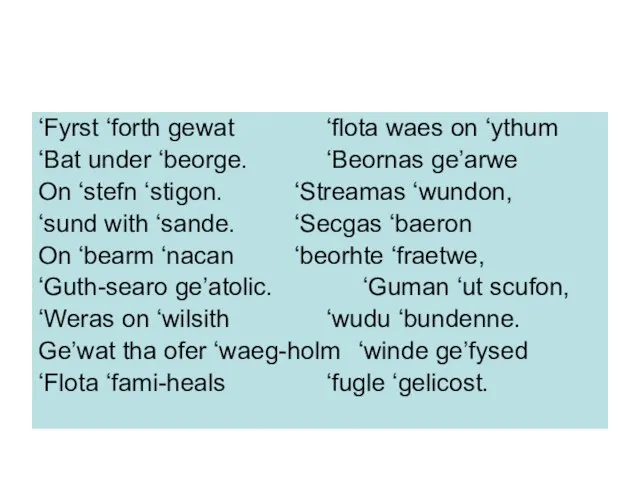

Слайд 2‘Fyrst ‘forth gewat ‘flota waes on ‘ythum

‘Bat under ‘beorge. ‘Beornas ge’arwe

On ‘stefn

‘stigon. ‘Streamas ‘wundon,

‘sund with ‘sande. ‘Secgas ‘baeron

On ‘bearm ‘nacan ‘beorhte ‘fraetwe,

‘Guth-searo ge’atolic. ‘Guman ‘ut scufon,

‘Weras on ‘wilsith ‘wudu ‘bundenne.

Ge’wat tha ofer ‘waeg-holm ‘winde ge’fysed

‘Flota ‘fami-heals ‘fugle ‘gelicost.

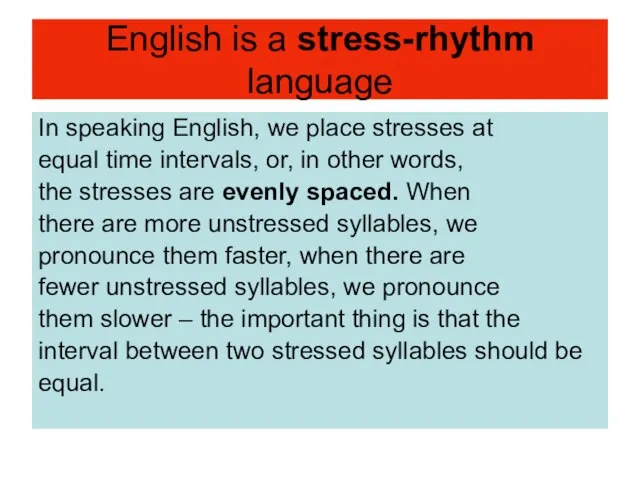

Слайд 3English is a stress-rhythm language

In speaking English, we place stresses at

equal time

intervals, or, in other words,

the stresses are evenly spaced. When

there are more unstressed syllables, we

pronounce them faster, when there are

fewer unstressed syllables, we pronounce

them slower – the important thing is that the

interval between two stressed syllables should be

equal.

Слайд 4French, for instance, is a length-rhythm

language: almost all syllables of equal

length.

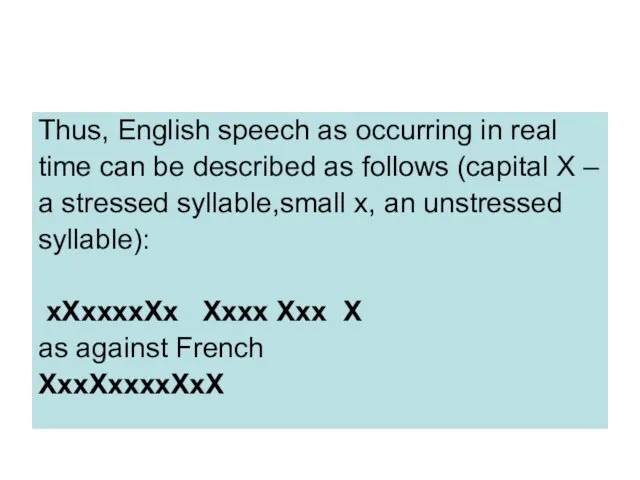

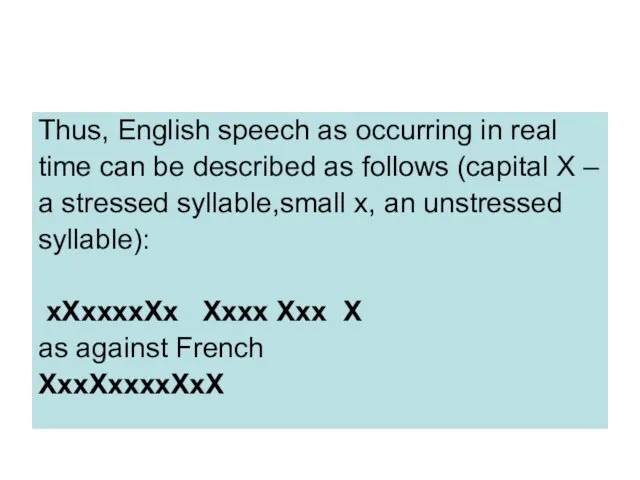

Слайд 5Thus, English speech as occurring in real

time can be described as follows

(capital X –

a stressed syllable,small x, an unstressed

syllable):

xXxxxxXx Xxxx Xxx X

as against French

XxxXxxxxXxX

Слайд 6The stress-rhythm nature of the English

language goes back to Old English times.

Ilse Lehiste: indigenous poetry is closely

linked to the phonetic nature of the

language.

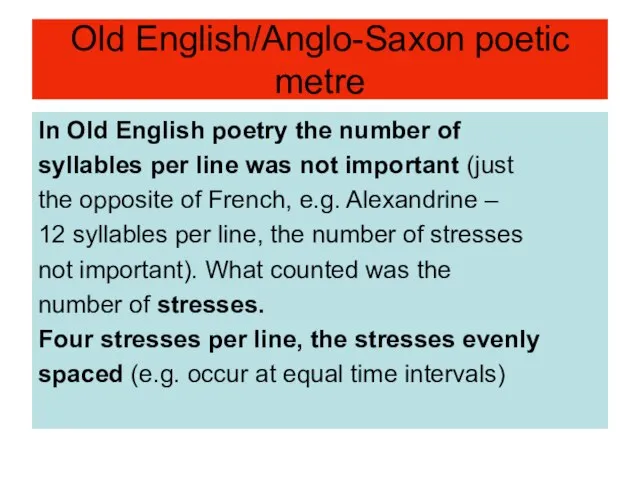

Слайд 7Old English/Anglo-Saxon poetic metre

In Old English poetry the number of

syllables per line

was not important (just

the opposite of French, e.g. Alexandrine –

12 syllables per line, the number of stresses

not important). What counted was the

number of stresses.

Four stresses per line, the stresses evenly

spaced (e.g. occur at equal time intervals)

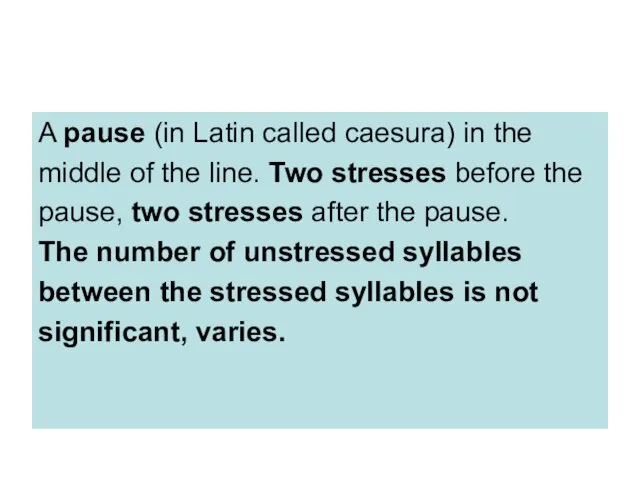

Слайд 8A pause (in Latin called caesura) in the

middle of the line. Two

stresses before the

pause, two stresses after the pause.

The number of unstressed syllables

between the stressed syllables is not

significant, varies.

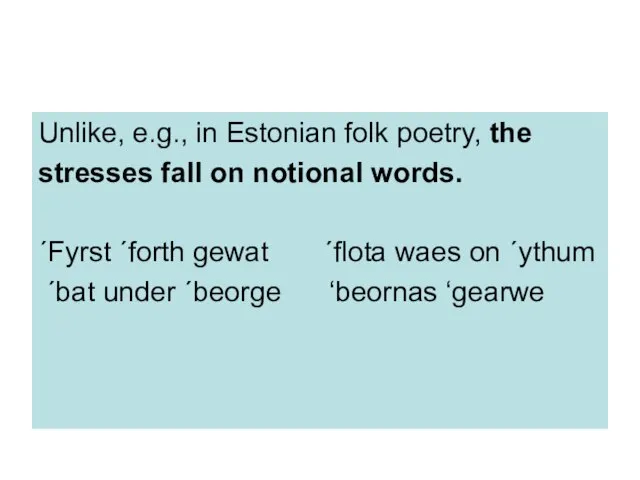

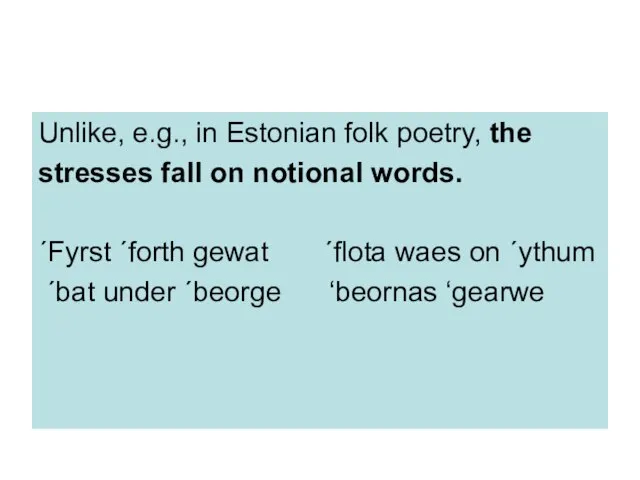

Слайд 9Unlike, e.g., in Estonian folk poetry, the

stresses fall on notional words.

´Fyrst ´forth

gewat ´flota waes on ´ythum

´bat under ´beorge ‘beornas ‘gearwe

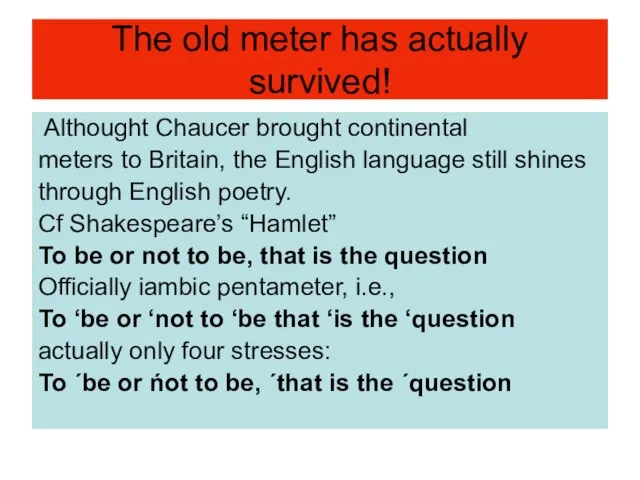

Слайд 10The old meter has actually survived!

Althought Chaucer brought continental

meters to

Britain, the English language still shines

through English poetry.

Cf Shakespeare’s “Hamlet”

To be or not to be, that is the question

Officially iambic pentameter, i.e.,

To ‘be or ‘not to ‘be that ‘is the ‘question

actually only four stresses:

To ´be or ńot to be, ´that is the ´question

Слайд 11The same applies to Chaucer himself:

´Whan that A´prille with his śhoures śoote

(Although

“should” be

Whan ´that A´prille ´with his śhoures śoote –

iambic pentameter)

Слайд 12The tension between the formal meter (i.e.

iambic pentameter) and the “real”

one (i.e.

the one that sounds natural and that all

actors actually use) creates a specific poetic

effect.

Слайд 13Alliteration

Old English poetry: initial rhymes (important

for remembering! After all, the poetry was

mainly

oral, only selected poems written

down by clerks at the command of

noblemen/kings).

Alliteration – consonants at the beginning of

words are repeated.

Alliteration applied to stressed syllables.

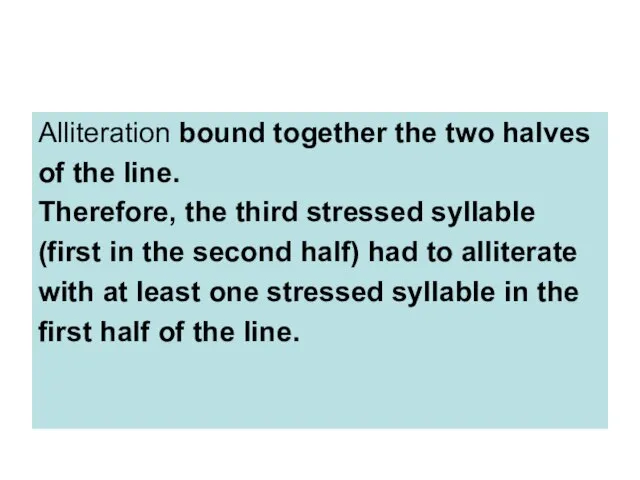

Слайд 14Alliteration bound together the two halves

of the line.

Therefore, the third

stressed syllable

(first in the second half) had to alliterate

with at least one stressed syllable in the

first half of the line.

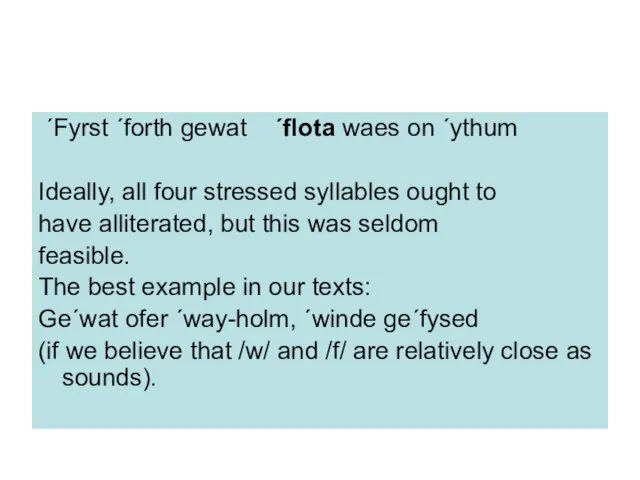

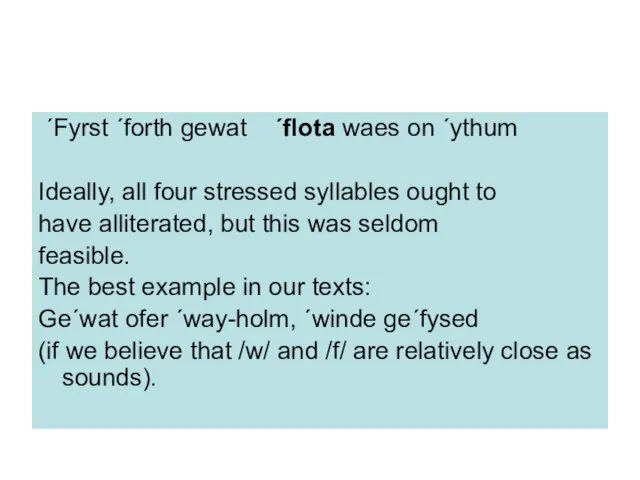

Слайд 15 ´Fyrst ´forth gewat ´flota waes on ´ythum

Ideally, all four stressed syllables

ought to

have alliterated, but this was seldom

feasible.

The best example in our texts:

Ge´wat ofer ´way-holm, ´winde ge´fysed

(if we believe that /w/ and /f/ are relatively close as sounds).

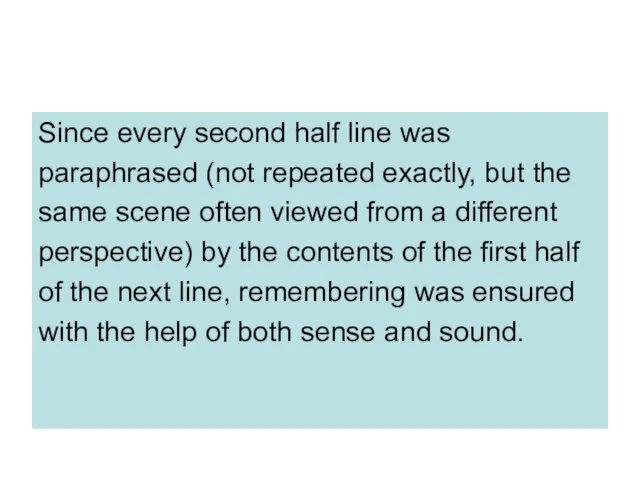

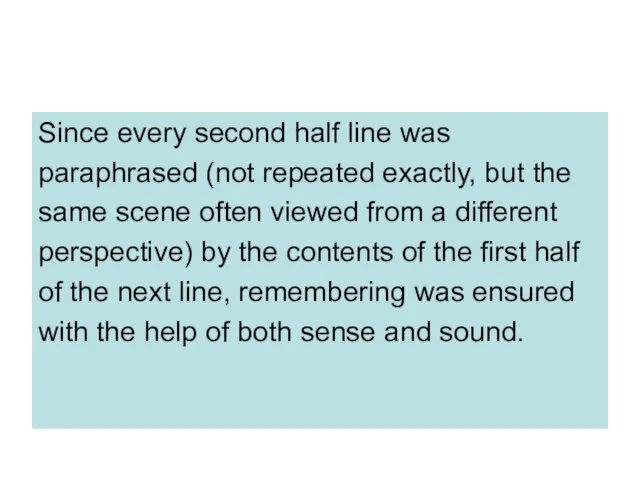

Слайд 16Since every second half line was

paraphrased (not repeated exactly, but the

same

scene often viewed from a different

perspective) by the contents of the first half

of the next line, remembering was ensured

with the help of both sense and sound.

Системы лояльности: современные тенденции развития

Системы лояльности: современные тенденции развития Теорема Виета доказательство

Теорема Виета доказательство Словообразовательные гнёзда полисемантичных имён существительных в русском и белорусском языках

Словообразовательные гнёзда полисемантичных имён существительных в русском и белорусском языках СМАЗКИ КАНАТНЫЕ

СМАЗКИ КАНАТНЫЕ Приемы рисования геометрических фигур

Приемы рисования геометрических фигур Metal-Insulator-Semiconductor and Metal-Insulator-Metal Structures

Metal-Insulator-Semiconductor and Metal-Insulator-Metal Structures "Я ЛЮБЛЮ ТЕБЯ,РОССИЯ!" Игра "Звездный час" (для учащихся 3-4классов)

"Я ЛЮБЛЮ ТЕБЯ,РОССИЯ!" Игра "Звездный час" (для учащихся 3-4классов) Три кита в музыке

Три кита в музыке Сбор изображений для тренировки системы распознавания номеров машин

Сбор изображений для тренировки системы распознавания номеров машин Презентация на тему Состав ядра. Ядерные силы (11 класс)

Презентация на тему Состав ядра. Ядерные силы (11 класс) Понятие мотивации. Мотивация по Риссу. Нейрологические уровни Дилтса. Модель ценностей Грейвза

Понятие мотивации. Мотивация по Риссу. Нейрологические уровни Дилтса. Модель ценностей Грейвза Финансовая политика РФ

Финансовая политика РФ Дециметр

Дециметр Материки и океаны

Материки и океаны Конституционное право - ведущая отрасль в правовой системе Российской Федерации. Лекция 1

Конституционное право - ведущая отрасль в правовой системе Российской Федерации. Лекция 1 Александр Родченко

Александр Родченко Спектры.Спектральный анализОткрытый урок

Спектры.Спектральный анализОткрытый урок Лепка фигуры человека

Лепка фигуры человека ОПСиП_ Семенова ПО-3

ОПСиП_ Семенова ПО-3 Градусная сеть на глобусе и географической карте

Градусная сеть на глобусе и географической карте Международный Юридический институт приглашает всех желающих на День Открытых дверей!

Международный Юридический институт приглашает всех желающих на День Открытых дверей! Страхование непредвиденных расходов автовладельцев полис «РЕСОавто ПОМОЩЬ»

Страхование непредвиденных расходов автовладельцев полис «РЕСОавто ПОМОЩЬ» Бюджет доходов и расходов БДР/P&L

Бюджет доходов и расходов БДР/P&L Лексика

Лексика אילו המצאות חדשות הומצאו בישראל ובעולם ?במאה ה?21 -במה תרומתם לאנושות

אילו המצאות חדשות הומצאו בישראל ובעולם ?במאה ה?21 -במה תרומתם לאנושות Главные и второстепенные члены предложения

Главные и второстепенные члены предложения Основные причины ухудшения зрения школьника

Основные причины ухудшения зрения школьника Качество и качества Власти: восприятие населения

Качество и качества Власти: восприятие населения