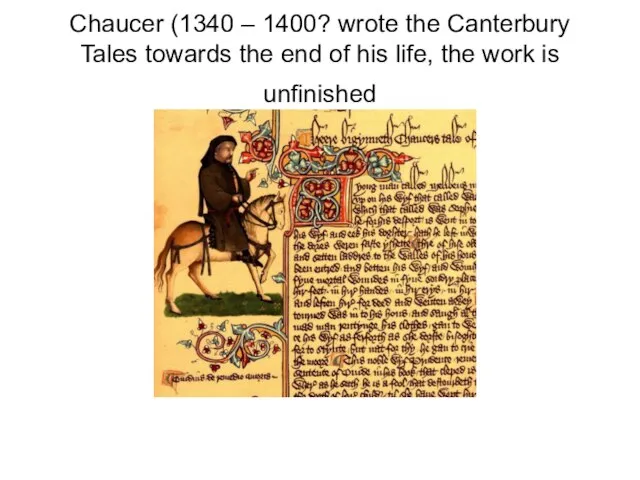

Слайд 2Chaucer (1340 – 1400? wrote the Canterbury Tales towards the end of

his life, the work is unfinished

Слайд 4“Who will rid me of this turbulent priest?” Murder in the cathedral

Слайд 5Pronunciation

http://academics.vmi.edu/english/audio/GP-opening.html

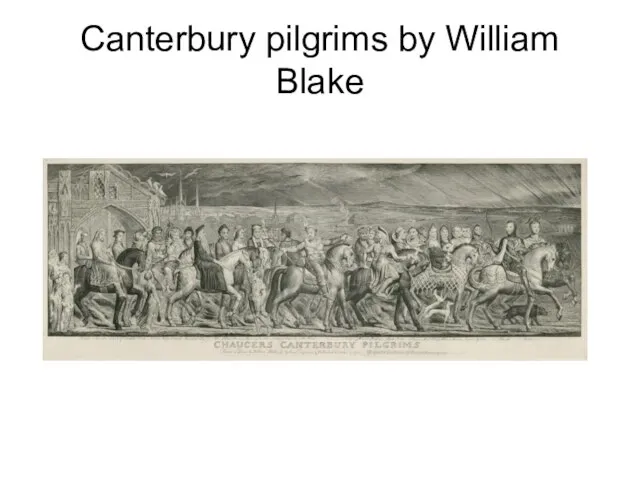

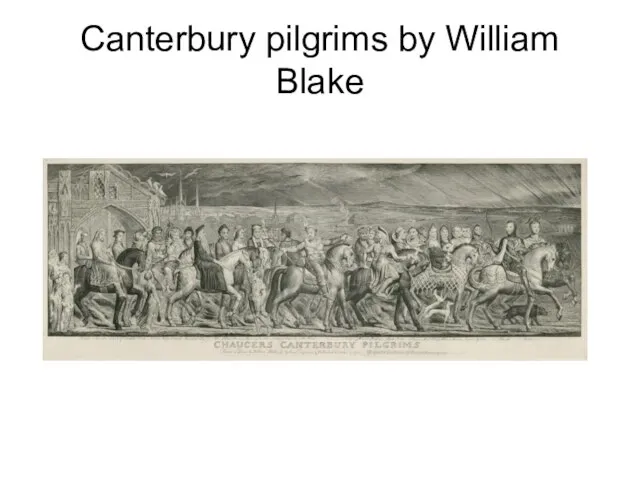

Слайд 6Canterbury pilgrims by William Blake

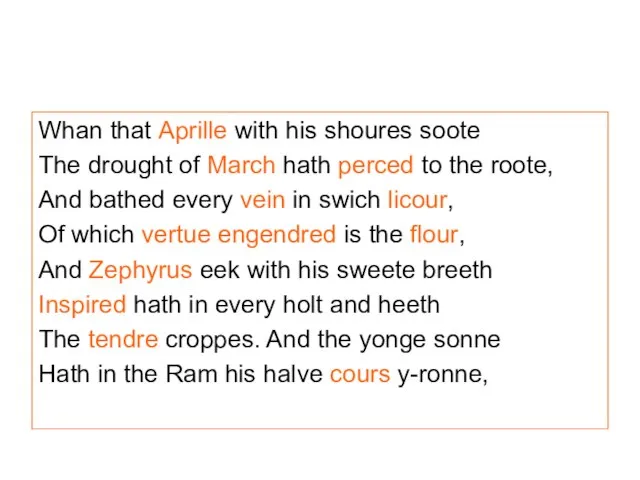

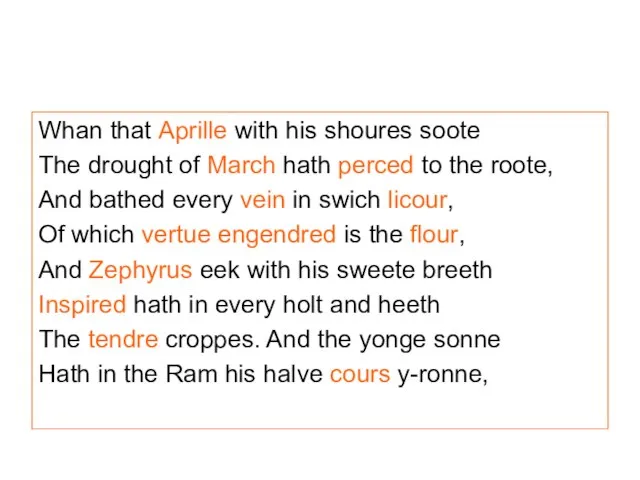

Слайд 7Whan that Aprille with his shoures soote

The drought of March hath perced

to the roote,

And bathed every vein in swich licour,

Of which vertue engendred is the flour,

And Zephyrus eek with his sweete breeth

Inspired hath in every holt and heeth

The tendre croppes. And the yonge sonne

Hath in the Ram his halve cours y-ronne,

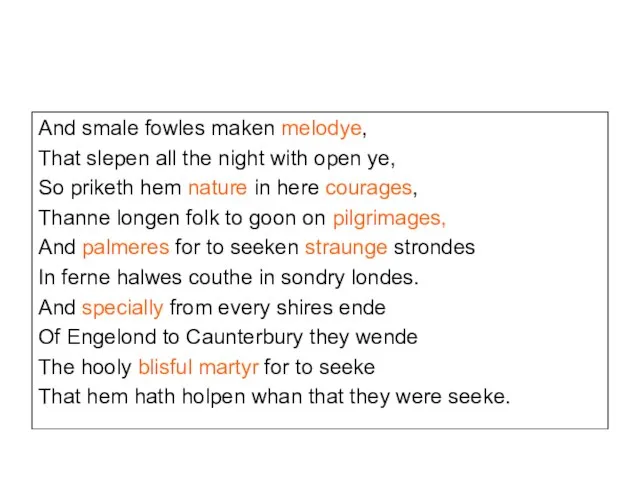

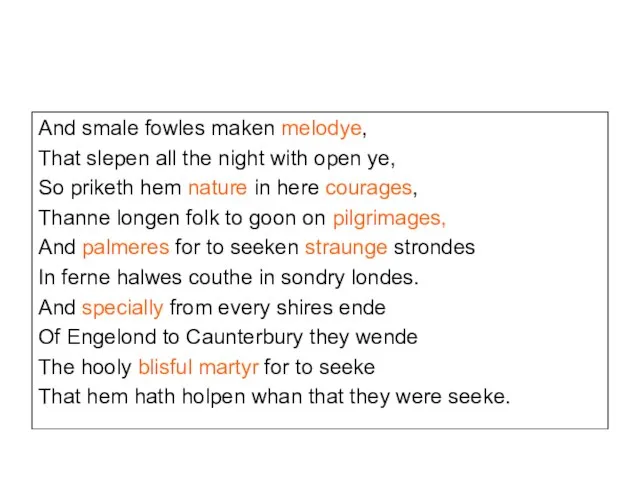

Слайд 8And smale fowles maken melodye,

That slepen all the night with open

ye,

So priketh hem nature in here courages,

Thanne longen folk to goon on pilgrimages,

And palmeres for to seeken straunge strondes

In ferne halwes couthe in sondry londes.

And specially from every shires ende

Of Engelond to Caunterbury they wende

The hooly blisful martyr for to seeke

That hem hath holpen whan that they were seeke.

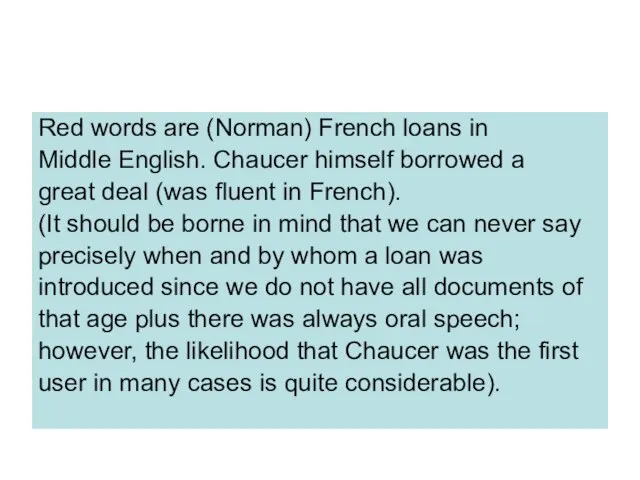

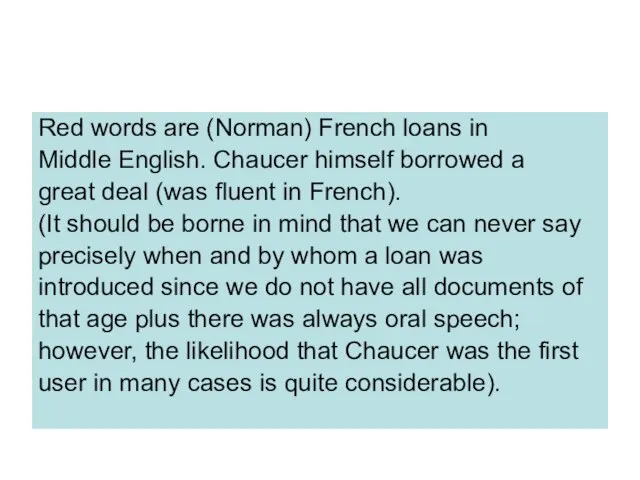

Слайд 9Red words are (Norman) French loans in

Middle English. Chaucer himself borrowed

a

great deal (was fluent in French).

(It should be borne in mind that we can never say

precisely when and by whom a loan was

introduced since we do not have all documents of

that age plus there was always oral speech;

however, the likelihood that Chaucer was the first

user in many cases is quite considerable).

Слайд 10Deterioration of meaning and loanwords

Wyrm in Old English meant ‘serpent

(dragon)’, now

worm

Stol in Old English meant ‘throne’

Слайд 11

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=OGUhHbBB0x4

&feature=related

Not obligatory!

For those temporarily tired of studying, something

directly based on this

(yet historically, obviously, totally

inaccurate!!! Thomas à Becket was born c.1118 and was

murdered on December 29, 1179, having been Archbishop

of Canterbury from 1162 to 1170. Becket was canonised

after his death, his burial place – Canterbury cathedral –

became a destination for pilgrimages).

The “Black Adder“ episode above (in 6 parts) plays on

the very real strife between the church and the king (that

did not end until the Reformation in 1533) and,

inspired by the story of Becket, pretends that all

Archbishops of Canterbury meet an early and violent death.

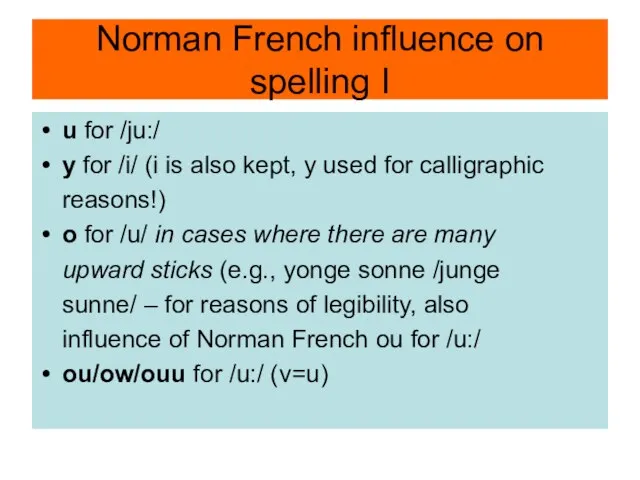

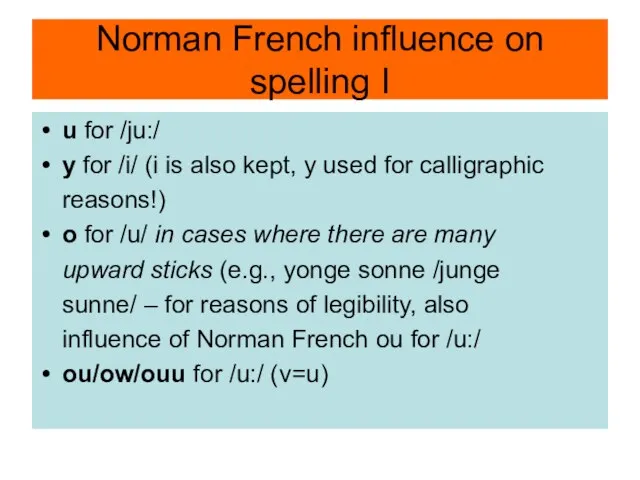

Слайд 12Norman French influence on spelling I

u for /ju:/

y for /i/ (i

is also kept, y used for calligraphic

reasons!)

o for /u/ in cases where there are many

upward sticks (e.g., yonge sonne /junge

sunne/ – for reasons of legibility, also

influence of Norman French ou for /u:/

ou/ow/ouu for /u:/ (v=u)

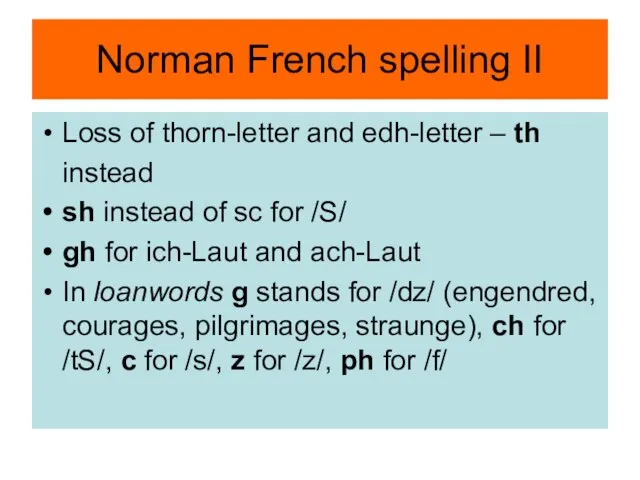

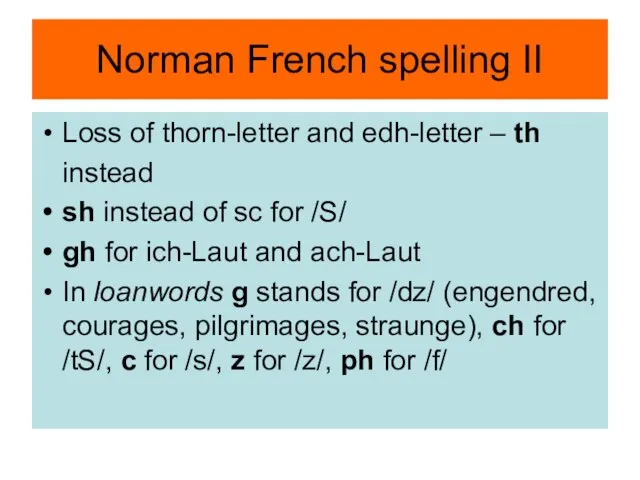

Слайд 13Norman French spelling II

Loss of thorn-letter and edh-letter – th

instead

sh instead

of sc for /S/

gh for ich-Laut and ach-Laut

In loanwords g stands for /dz/ (engendred, courages, pilgrimages, straunge), ch for /tS/, c for /s/, z for /z/, ph for /f/

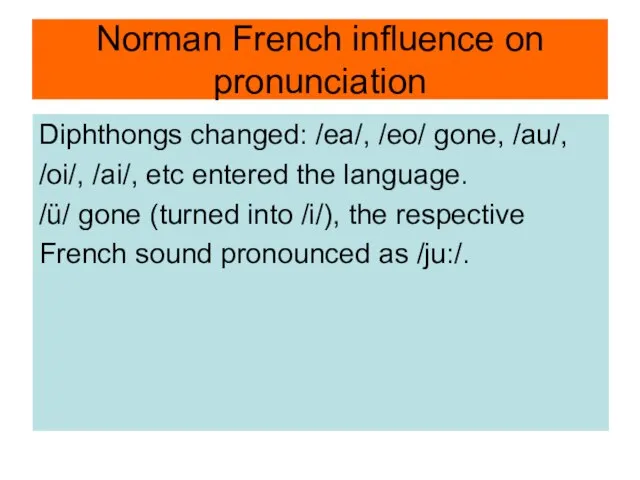

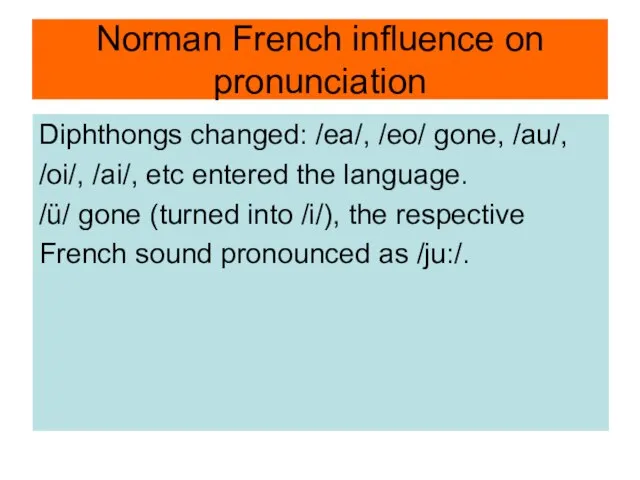

Слайд 14Norman French influence on pronunciation

Diphthongs changed: /ea/, /eo/ gone, /au/,

/oi/, /ai/,

etc entered the language.

/ü/ gone (turned into /i/), the respective

French sound pronounced as /ju:/.

Слайд 15However, in the main the pronunciation did

not change, this was still

a pre-Great-

Vowel-shift time:

e - /e:/, i - /i:/, a /a:/, ow - /u:/, etc.

Ich-Laut, ach-Laut still there.

Short vowels also have the so-called

continental pronunciation.

Слайд 16Important: e at the end of words and even

word-internally could be

pronounced but

did not have to be pronounced. In the

case of Chaucer the main rule is: pronounce

them if this is called for by the metre (iambic

pentameter).

For a time this was forgotten, hence Dryden called

Chaucer a “rough diamond” – i.e. a genius who

was not able to keep the metre – wrong!

Слайд 17Grammar: levelled endings.

The principle of analogy:

Old English:

fot – fet /fo:t/ - /fe:t/

boc

– bec /bo:k/ - /be:k/

But :

stan – stanas – far more frequent

Слайд 18Analogy

ston – stones (from Old English Stan –

stanas)

boc – X

X =

boces/bookes.

Two opposing tendencies in the history of any

language

1) ease of pronunciation (sound laws – regular, but

produce grammatical irregularity)

2) Link between sound and sense (analogy –

irregular but produces grammatical regularity)

Слайд 19Iconicity

Analogy produces iconicity: a relation of

equivalence between sense and sound.

Most obvious

case of iconicity:

onomatopoea.

However, there are many more types of iconicity:

No known language has a plural form that is shorter than the respective singular,

Same ending for the same meaning:

stones, books, etc (i.e. all plurals end in s)

Order of clauses the same as order of events

(“They married and had a child” versus “They had a child and married”), etc.

Слайд 20The grammar of Middle English more

iconic than that of Old English,

that of

Modern English even more so.

Слайд 21Middle English: articles in place (i.e. compulsory).

While in Estonian the unstressed

“see” and “üks”

also perform the function of articles, their use is

not regulated by obligatory rules (“Pane see

raamat lauale” – “Put the book on the table” – in

Estonian, we can say “Pane raamat lauale”, and it

would be very unidiomatic to say “Pane see

raamat sellele lauale”).

Слайд 22His – both in Old English and in Middle

English the genitive

(possesive) form of

both he and hit was his.

Its is the latest addition to the English

pronoun system: Shakespeare (16th

century) used its and his as neuter

possessive (genitive) interchangeably. Milton (17th

century) was more of a linguistic purist, its was still

considered as a “vulgar” form, only 3 cases of

usage in his works.

Слайд 23Middle English: perfect tenses (hath y-

ronne): were formed roughly on the

following

logic:

“I had this picture put up on the wall” – “I had

put this picture up on the wall”

Слайд 24drought - nowadays means “põud”, original

meaning: “dryness” (*driug – dry –

a

Germanic root)

Слайд 25hath – has

(cf the Biblical idiom “pride goeth/goes

before the fall”

– still used also in the old,

the Shakespearean idiom “Heaven hath no

fury like a woman scorned”)

Hath pierced – Present Perfect (see above

the introduction of analytical tenses into

English)

Слайд 26licour – Middle English from Old French

(liquid, beverage)

(cf Present-Day American English

liquor –

strong alcohol; does also mean occasionally

other liquids – broth or juice as produce in

cooking, pharmaceutical liquids)

Слайд 27of which vertue – by virtue of which, by the

strength of

which

(i.e. Present-Day BY VIRTUE OF – because

of, by the strength of)

Слайд 28engendred – created

TO ENGENDER – to bring into existence, to

give rise

to, to produce, i.e.usually figurative,

but also: to procreate, propagate

Слайд 29Zephirus – (Greek mythology) west wind

(warm)

Слайд 30eek – also (German auch)

Cf EKE OUT (e.g., a salary by doing

odd

jobs – Middle English eken – to increase)

Слайд 31holt – a grove, a copse (i.e. small wood) – can be

found in the Heritage dictionary of English, marked as Archaic;

German: Holz - timber

Слайд 32heeth – HEATH

tendre – TENDER

croppes – shoots (võsud), cf to CROP

UP

CROP (cultivated plants, yearly yield of such

plants, British HARVEST)

Слайд 33the Ram (Jäär) – the Zodiac sign of Aries

hath y-ronne – Present

Perfect

Notice the prefix y! In Chaucer’s time it had

survived in the Kentish dialect (Chaucer

came from Kent), remnant of Old English

ge- (see the notes on Beowulf!).

YCLEPT, YCLAD – archaic past participle

forms, still recorded in dictionaries, especially the

former one(“so-called” and “clothed”, respectively).

Слайд 34fowl – check notes on “Beowulf”, notice the

new spelling, the pronuciation

is still /fu:l/,

the meaning is still bird!

hem – accusative of the old form of they.

they (a Scandinavian loan – their –

combined with tha in Old English) was just

entering the language and replacing the old

hie. The transition is best exemplified in the line

“That hem hath holpen whan that they were

seeke”).

Слайд 35 here – old form of their

courage – first meaning “courage”, metonymically means

“heart” (courage was thought to be located in the heart, cf Present-Day English “TO TAKE HEART” = to pluck up courage; TO LOSE HEART = be discouraged, TO HEARTEN – to encourage; cf also Estonian “südant rindu võtma”, “süda saapasääres”). The interesting point here is that normally the concrete noun is used instead of the abstract one, here the abstract noun (courage) is used instead of the concrete one (heart).

Слайд 36thanne – then, THEN

longen (present plural) – long, yearn, want,

wish

folk -

people (PEOPLE is a French loan),

FOLK – very much alive in American English

(“folks back home”, “my folks”, etc.,

particularly popular in the Southern states).

Cf Present-Day German Volk.

Слайд 37To goon – to go

Cf later wenden – turn, go (present plural).

Слайд 38Suppletivity = suppletion I

Present in languages of different families.

Present in Old,

Middle and Modern English,

though the general tendency is towards

more regularity/iconicity so the number of

suppletive forms has decreased.

In the text:

goon – to go

wenden - to turn

Слайд 39Suppletion II

Gan was suppletive in Old English, past

form: eode.

Eode was supplanted

by went (past form of

wenden) at the end of the Middle English

period.

To wend has survived in Modern English in

phrases such as

to wend one’s way, we wended homewards

(ironic usage).

Слайд 40Suppletion III

Thus: suppletivity- suppletion – different

parts of one and the same

paradigm come

from what were originally different

paradigms (different words with close

meanings or words in different but close

dialects).

Suppletion embraces verbs, adjectives,

nouns.

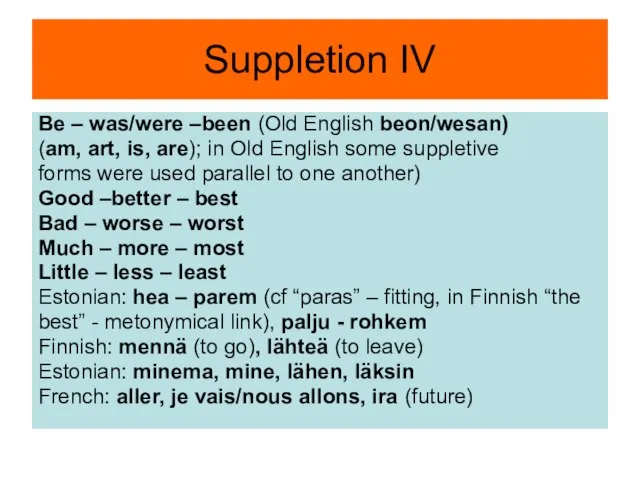

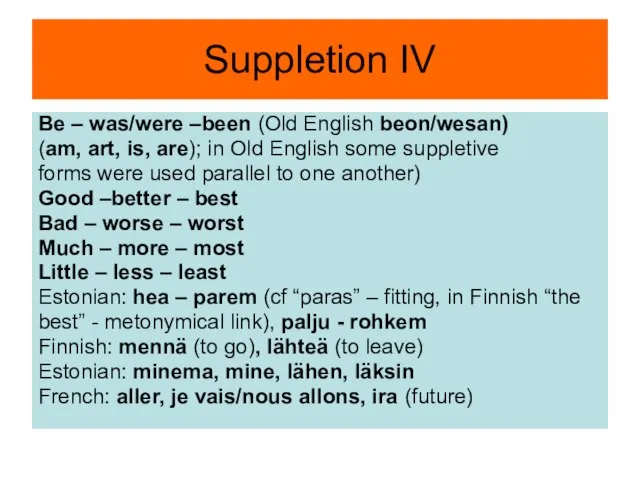

Слайд 41Suppletion IV

Be – was/were –been (Old English beon/wesan)

(am, art, is, are);

in Old English some suppletive

forms were used parallel to one another)

Good –better – best

Bad – worse – worst

Much – more – most

Little – less – least

Estonian: hea – parem (cf “paras” – fitting, in Finnish “the

best” - metonymical link), palju - rohkem

Finnish: mennä (to go), lähteä (to leave)

Estonian: minema, mine, lähen, läksin

French: aller, je vais/nous allons, ira (future)

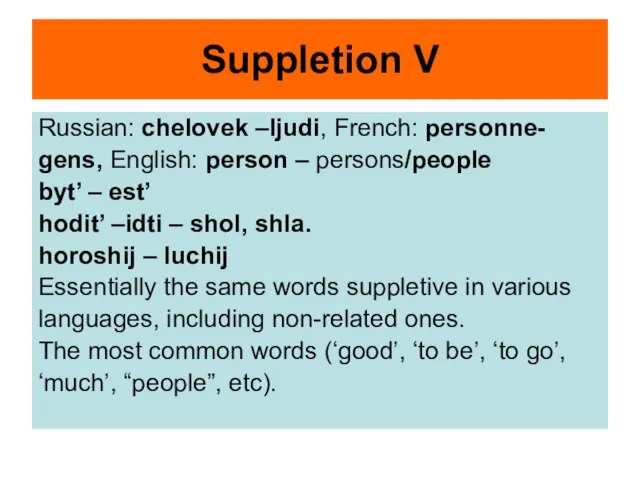

Слайд 42Suppletion V

Russian: chelovek –ljudi, French: personne-

gens, English: person – persons/people

byt’ –

est’

hodit’ –idti – shol, shla.

horoshij – luchij

Essentially the same words suppletive in various

languages, including non-related ones.

The most common words (‘good’, ‘to be’, ‘to go’,

‘much’, “people”, etc).

Слайд 43Suppletion VI

General principle: the more frequently

used a word, the more one

can “afford” it

to be irregular/non-iconic. (Frequent

words are not a burden to memory).

Suppletion perhaps the most drastic form of

irregularity/iconicity), covers mainly the most

frequent words.

Слайд 44Suppletion VII

Increase of iconicity/regularity appears to be

a general tendency in language

history –

probably related to increased vocabulary

which means that every particular word is

used less frequently.

Latin was full of suppletive verbs (e.g. fero-

tuli-latum-ferre - to carry), many have

become regular in, say, Italian or French.

Слайд 45General principle: the more frequently used a

word, the more one can

“afford” it to be

irregular/non-iconic.

This also applies to “less irregular” words: the so-called

strong verbs (German “starke Verben”) – those that have

their forms made up by

Ablaut/gradation, such as bear-bore-born(e) are also very

frequent in oral speech and texts. The number of such

verbs has shrunk in English (Old English just over 300 –

the same number as in Present-Day German! – Modern

English100; plus new irregular verbs such as let,

put, etc – here ease of pronunciation has been at work

(“letted”, “putted” difficult to pronounce)

Слайд 46The same applies, e.g., to irregular plurals such

as foot - feet,

man - men, woman - women,

child - children, tooth-teeth, goose-geese, ox –

oxen, mouse - mice, louse-lice (in the case of

the latter two one must keep in mind frequency at

the time when analogy levelled all declensions

under one: mice, lice and oxen were common,

books were not!

Слайд 47Palmeres – pilgrims to remote shrines, esp.

Jerusalem (brought palm leaves back

to

prove they had been there; could have got

these from Santiago de Compostela, which

was much nearer to England, with a less

dangerous journey!)

Слайд 48for to – in order to, to

(cf nursery rhymes:

“Simple Simon went a-fishing

For

to catch a whale …”)

Слайд 49straunge – STRANGE, not just strange, but

also foreign (cf French étranger,

à

l’étranger - abroad).

strond/strand – shore (THE STRAND in

London, STRANDED), cf German

Strand,Estonian rand

Слайд 50fern – distant, far-away (FAR). Cf German

fern (adjective and adverb –

kauge, kaugel).

In Early Modern English er turned into ar,

sometimes this is reflected in spelling (as in

FAR, HARK(EN)), sometimes not (Derby, clerk,

Berkeley). In America, the change did not

occur, hence the pronunciations /de:bi/, /kle:k/,

/be:kli/, where British English has /a:/.

Слайд 51The name of the letter r turned from the

continental er to

ar, later /r/ was dropped at

the end of syllables (in British English) so a

consonant is now pronounced as /a:/.

Слайд 52halwe – saint, metonymically shrine

HALLOW

Hooly – HOLY

Слайд 53halig – holy, HOLY

Long /a:/ turned into long /o:/ at the

beginning of

the Middle English period. The

change happened in Southern England

only.

During the Great Vowel Shift long /o:/ turned

into /ou/. In Scottish English still forms such

as hame for home.

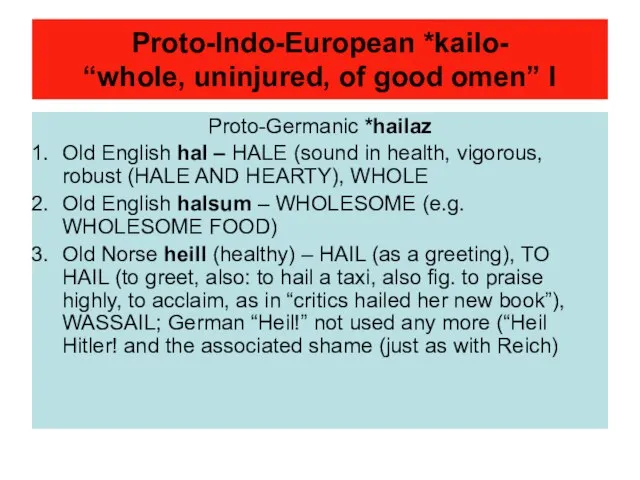

Слайд 54Proto-Indo-European *kailo-

“whole, uninjured, of good omen” I

Proto-Germanic *hailaz

Old English hal –

HALE (sound in health, vigorous, robust (HALE AND HEARTY), WHOLE

Old English halsum – WHOLESOME (e.g. WHOLESOME FOOD)

Old Norse heill (healthy) – HAIL (as a greeting), TO HAIL (to greet, also: to hail a taxi, also fig. to praise highly, to acclaim, as in “critics hailed her new book”), WASSAIL; German “Heil!” not used any more (“Heil Hitler! and the associated shame (just as with Reich)

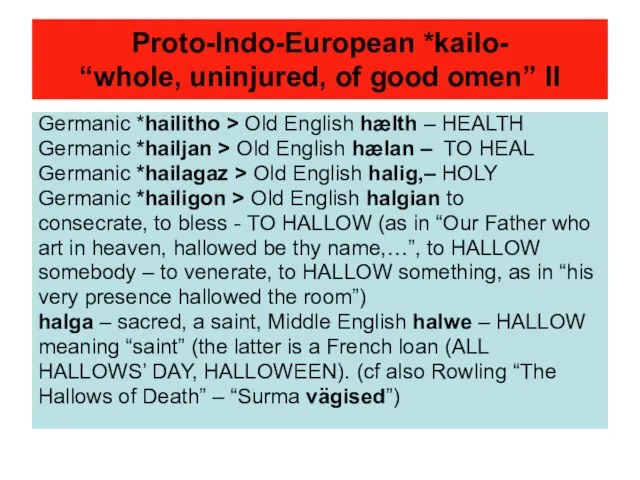

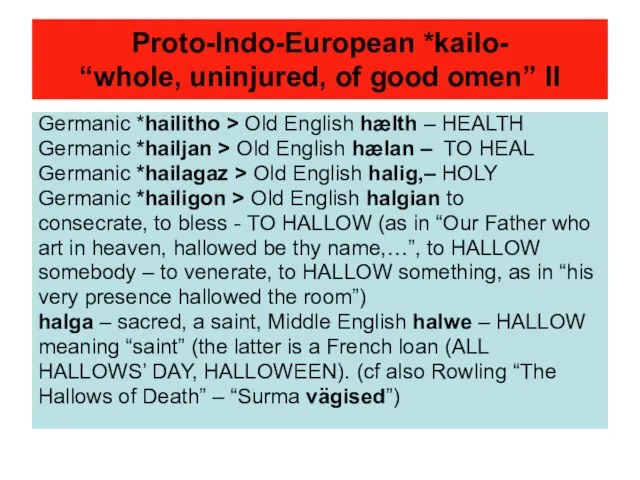

Слайд 55Proto-Indo-European *kailo-

“whole, uninjured, of good omen” II

Germanic *hailitho > Old English hælth

– HEALTH

Germanic *hailjan > Old English hælan – TO HEAL

Germanic *hailagaz > Old English halig,– HOLY

Germanic *hailigon > Old English halgian to

consecrate, to bless - TO HALLOW (as in “Our Father who

art in heaven, hallowed be thy name,…”, to HALLOW

somebody – to venerate, to HALLOW something, as in “his

very presence hallowed the room”)

halga – sacred, a saint, Middle English halwe – HALLOW

meaning “saint” (the latter is a French loan (ALL

HALLOWS’ DAY, HALLOWEEN). (cf also Rowling “The

Hallows of Death” – “Surma vägised”)

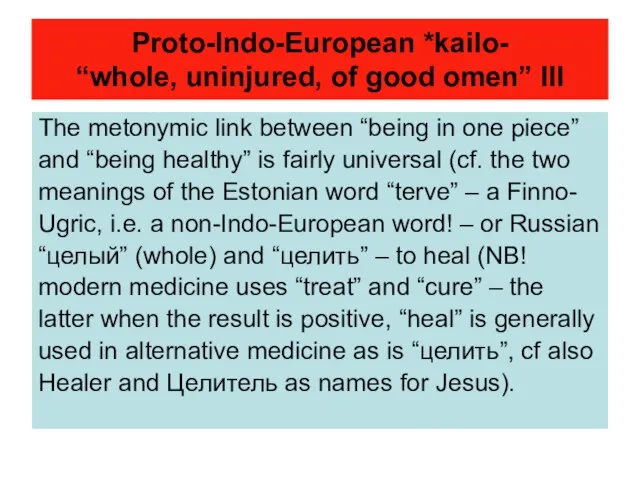

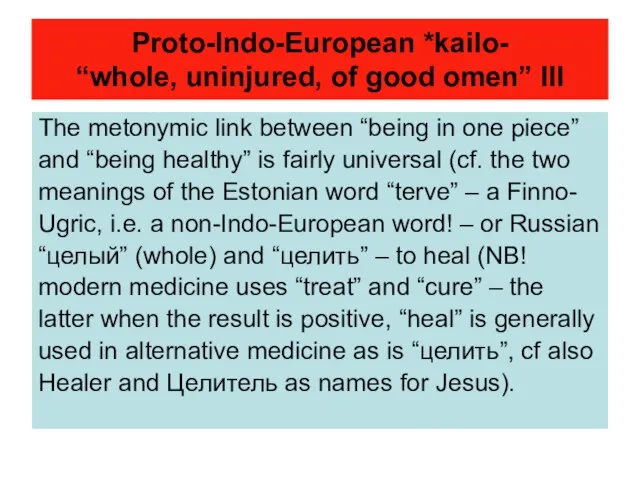

Слайд 56Proto-Indo-European *kailo-

“whole, uninjured, of good omen” III

The metonymic link between “being in

one piece”

and “being healthy” is fairly universal (cf. the two

meanings of the Estonian word “terve” – a Finno-

Ugric, i.e. a non-Indo-European word! – or Russian

“целый” (whole) and “целить” – to heal (NB!

modern medicine uses “treat” and “cure” – the

latter when the result is positive, “heal” is generally

used in alternative medicine as is “целить”, cf also

Healer and Целитель as names for Jesus).

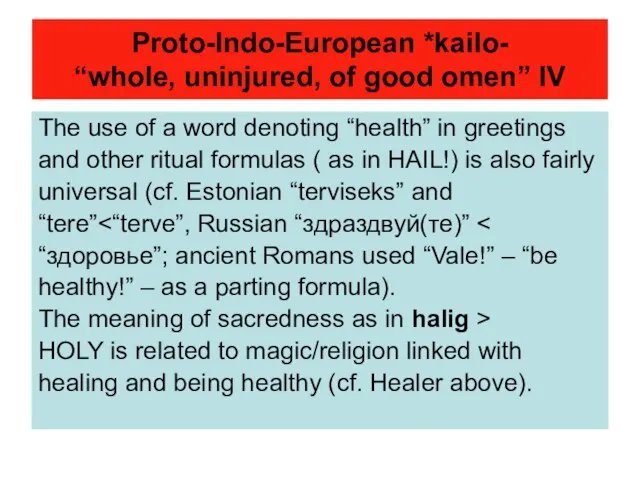

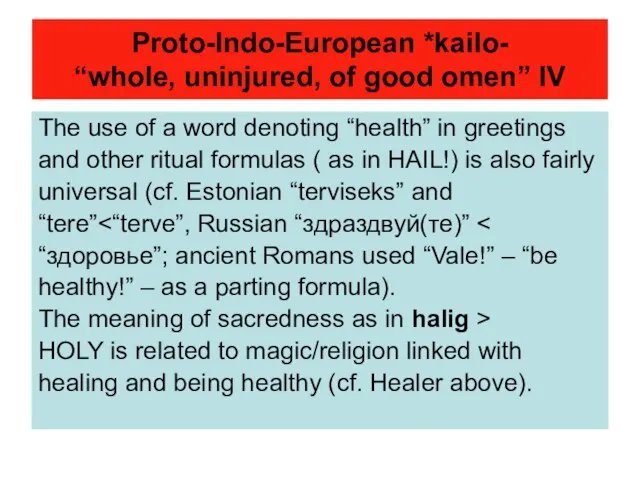

Слайд 57Proto-Indo-European *kailo-

“whole, uninjured, of good omen” IV

The use of a word denoting

“health” in greetings

and other ritual formulas ( as in HAIL!) is also fairly

universal (cf. Estonian “terviseks” and

“tere”<“terve”, Russian “здраздвуй(те)” <

“здоровье”; ancient Romans used “Vale!” – “be

healthy!” – as a parting formula).

The meaning of sacredness as in halig >

HOLY is related to magic/religion linked with

healing and being healthy (cf. Healer above).

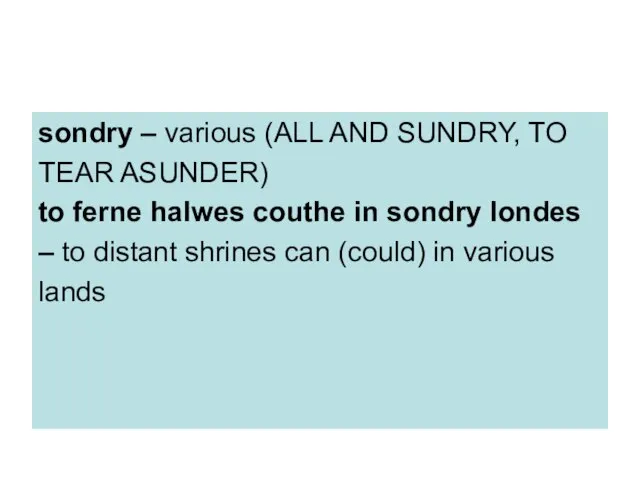

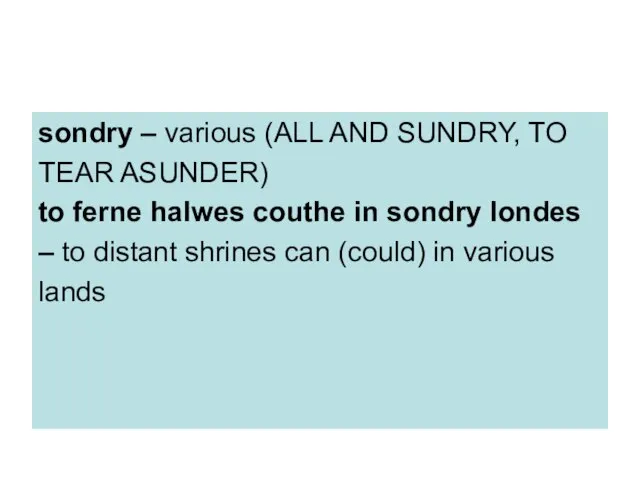

Слайд 58sondry – various (ALL AND SUNDRY, TO

TEAR ASUNDER)

to ferne halwes couthe

in sondry londes

– to distant shrines can (could) in various

lands

Слайд 59shire – county (as in present-day

placenames, e.g. Derbyshire). Shire +

reeve

= SHERIFF (a disguised compound,

cf “Ohthere’s voyage”)

blissful – blessed (BLISSFUL nowadays

means “full of bliss, extremely happy”)

Слайд 60for to seeke – to (in order to) seek

holpen – notice that

y- has already been dropped, but it is

still a strong (Ablaut/gradation) verb, just like the Present-

Day German helfen – half – geholfen – to help. German

only has this one word for “help”, whereas English has

borrowed aid, assist and succour from French

(plus rescue, and there are also phrasal units like

give somebody a hand”, etc).

Слайд 61HELP used less frequently due to the existence of

synonyms, has become

iconic/regular (HELP,

HELPED, HELPED). A good example of how

expansion of vocabulary leads to more

grammatical iconicity (remember, Present-Day

English has 500 000 words, Present-

Day German 180 000, Present-Day French 130

000 – according to the largest dictionaries of the

respective languages).

Слайд 62whan that they were seeke – when they

were ill (American English

SICK).

Слайд 63In many respects American English, though usually

associated with modernity and (often

rightfully) with

innovation, has retained forms that were in the language in

Shakespeare’s time. (First settlement 1604, Shakespeare’s

death – 1616). British English has “a sick child”,

but “the child is ill” (“sick” after the copula would mean

actually vomitting), in American English “the child is sick” is

used for illness in general. Cf also the pronunciation of “er”,

the Subjunctive mood (“I move that the meeting be (British

should be) adjourned”).

Слайд 64Finally, an approximate translation:

When April with its showers sweet

The dryness of March

has utterly destroyed

(“pierced to the root”)

And bathed every sap-vessel/crack in the

earth in such moisture

By virtue of which the flower is brought into existence

Слайд 65When Zephyrus also with is sweet breath

Inspired has in every grove and

heath

The tender shoots (new plants); and the young sun

Has in the Aries its half-course run,

And small birds sing

That sleep all the night with open eye,

So pricks them nature in their hearts

Подготовка к ЕГЭ

Подготовка к ЕГЭ Животноводство России

Животноводство России Путешествие по сказочным тропинкам

Путешествие по сказочным тропинкам Молоко. Молочные продукты

Молоко. Молочные продукты Психолог в отделе полиции

Психолог в отделе полиции 24 апреля 1915 года младотурецкие правители Талаат-паша, Энвер-паша и Джемаль-паша — приказали собрать всю армянскую интеллигенцию в

24 апреля 1915 года младотурецкие правители Талаат-паша, Энвер-паша и Джемаль-паша — приказали собрать всю армянскую интеллигенцию в Программа строительства и реконструкции котельных муниципальных образований Московской области - приоритетный инвестиционный п

Программа строительства и реконструкции котельных муниципальных образований Московской области - приоритетный инвестиционный п Глобальный экологический университет (по улучшению качества жизни)

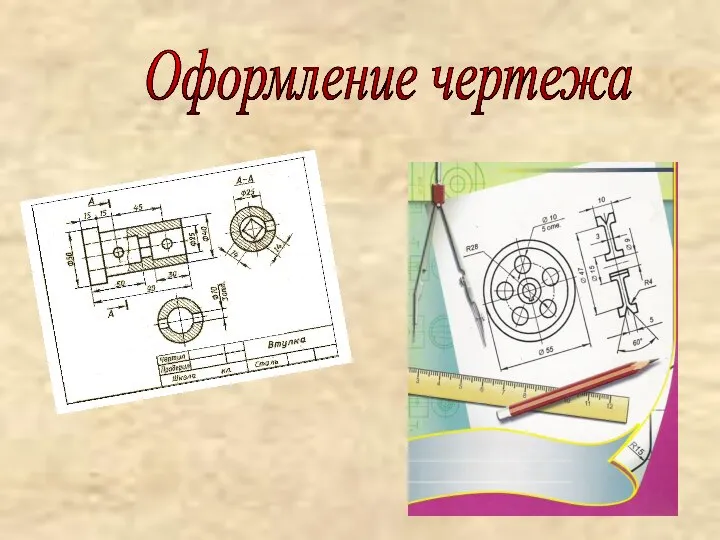

Глобальный экологический университет (по улучшению качества жизни) Оформление чертежа

Оформление чертежа ЕДИНАЯ ИНТЕЛЛЕКТУАЛЬНАЯ СИСТЕМА УПРАВЛЕНИЯ И АВТОМАТИЗАЦИИ ПРОИЗВОДСТВЕННЫХ ПРОЦЕССОВ НА ЖЕЛЕЗНОДОРОЖНОМ ТРАНСПОРТЕ (ИСУЖТ)

ЕДИНАЯ ИНТЕЛЛЕКТУАЛЬНАЯ СИСТЕМА УПРАВЛЕНИЯ И АВТОМАТИЗАЦИИ ПРОИЗВОДСТВЕННЫХ ПРОЦЕССОВ НА ЖЕЛЕЗНОДОРОЖНОМ ТРАНСПОРТЕ (ИСУЖТ) Ландшафтный дизайн и озеленение участка

Ландшафтный дизайн и озеленение участка Кальянные миксы. Обеспечь себе истинное наслаждение

Кальянные миксы. Обеспечь себе истинное наслаждение Презентация на тему Логические операции

Презентация на тему Логические операции Хатеновская Елена Васильевна

Хатеновская Елена Васильевна SK700-II (Sandpiper II Electronics)

SK700-II (Sandpiper II Electronics) Духовная сфера общества. Религия

Духовная сфера общества. Религия Equalizer

Equalizer XIII Международная конференция "Маркетинг в России" Сообщение: «ОСОБЕННОСТИ ОНЛАЙН ИССЛЕДОВАНИЙ В РОССИИ» Александр Шашкин (Online Market

XIII Международная конференция "Маркетинг в России" Сообщение: «ОСОБЕННОСТИ ОНЛАЙН ИССЛЕДОВАНИЙ В РОССИИ» Александр Шашкин (Online Market  Здравствуй, милая картошка!

Здравствуй, милая картошка! ИСТОРИЯ РОССИИ

ИСТОРИЯ РОССИИ Полисахариды

Полисахариды Презентация на тему Труд земной. Ремесла на Руси

Презентация на тему Труд земной. Ремесла на Руси Saxotech 170

Saxotech 170 Внешняя политика СССР

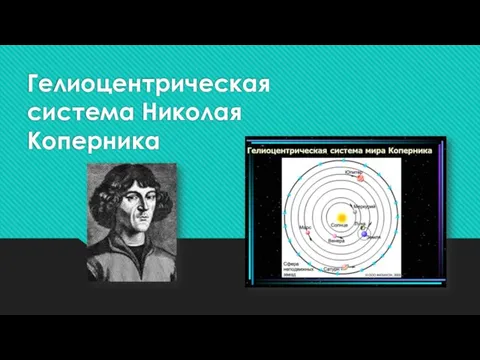

Внешняя политика СССР Гелиоцентрическая система Николая Коперника

Гелиоцентрическая система Николая Коперника Шираб-Жамсо Раднаев

Шираб-Жамсо Раднаев «Давньогрецька міфологія як основа формування філософії та розвитку Європейської цивілізації в цілому»

«Давньогрецька міфологія як основа формування філософії та розвитку Європейської цивілізації в цілому» Их лик сияет над Симбирском

Их лик сияет над Симбирском