Содержание

- 2. Pneumonia – polyetiological infectious disease of respiratory system lower parts with alveolar exudation which is confirmed

- 3. Etiologic Agents

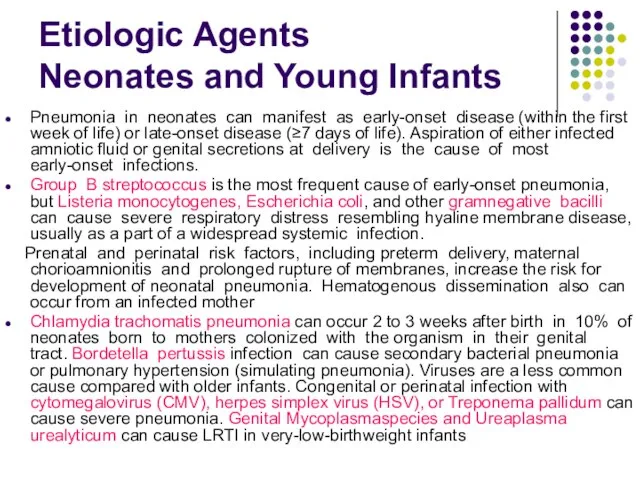

- 4. Etiologic Agents Neonates and Young Infants Pneumonia in neonates can manifest as early-onset disease (within the

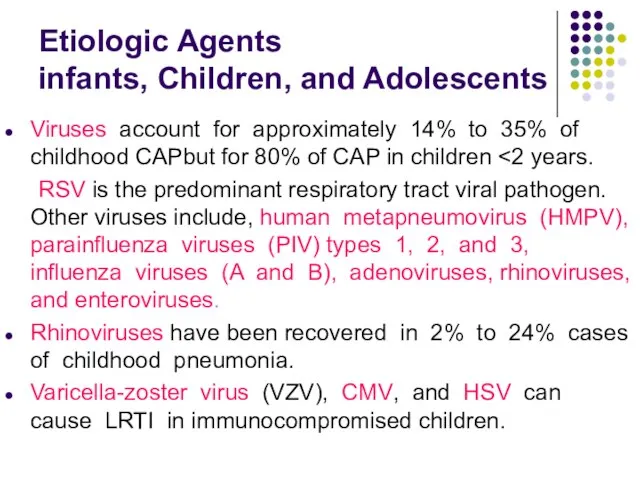

- 5. Etiologic Agents infants, Children, and Adolescents Viruses account for approximately 14% to 35% of childhood CAPbut

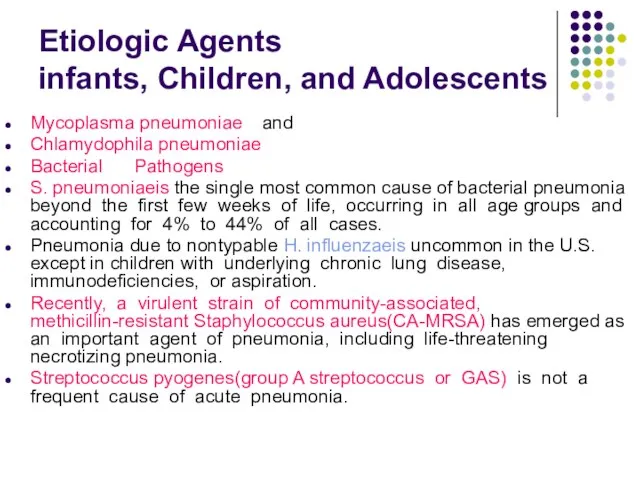

- 6. Etiologic Agents infants, Children, and Adolescents Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae Bacterial Pathogens S. pneumoniaeis the

- 7. Pathogenesis and Pathology

- 8. The pulmonary defense mechanisms Physical barriers of the respiratory tract include the presence of hairs in

- 9. The pulmonary defense mechanisms Mucociliary transport moves normally aspirated oropharyngeal flora and particulate matter up the

- 10. Pneumonia is inflammatory process developed after entry of infectious agent in respiratory portions of airway tract.

- 11. There are 4 ways of pulmonary contamination with pathogens: 1. Aspiration of oropharyngeal contents (microaspiration in

- 12. Pathogenesis of acute pneumonia First – contamination with microorganisms, inflammatory obstruction of upper respiratory ways, disorder

- 13. Pathogenesis of acute pneumonia Third – alteration of not only pathogen but of own organism including

- 14. Pathogenesis of acute pneumonia Fifth – development of respiratory insufficiency and non-respiratory pulmonary functions. Sixth –

- 15. Viruses affection Viral respiratory infections can lead to bronchiolitis, interstitial pneumonia, or parenchymal infection, with overlapping

- 16. Bacteria affection Five pathologic patterns are seen with bacterial pneumonia: 1)parenchymal inflammation of a lobe or

- 17. Stages of lobar pneumonia 1. In the first stage, which occurs within 24 hours of infection,

- 18. Classification

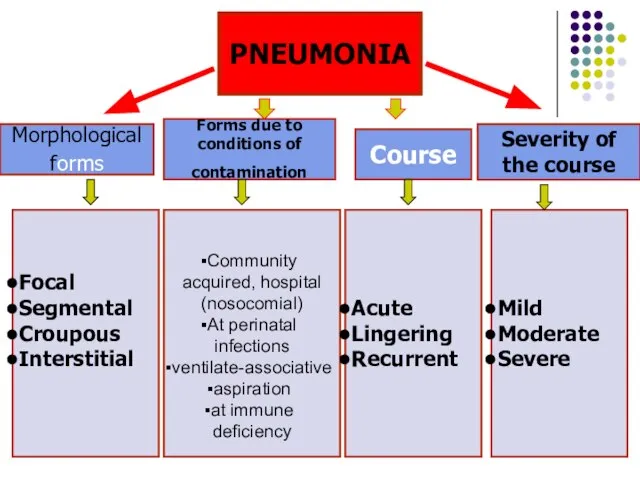

- 19. PNEUMONIA Morphological forms Forms due to conditions of contamination Course Severity of the course Focal Segmental

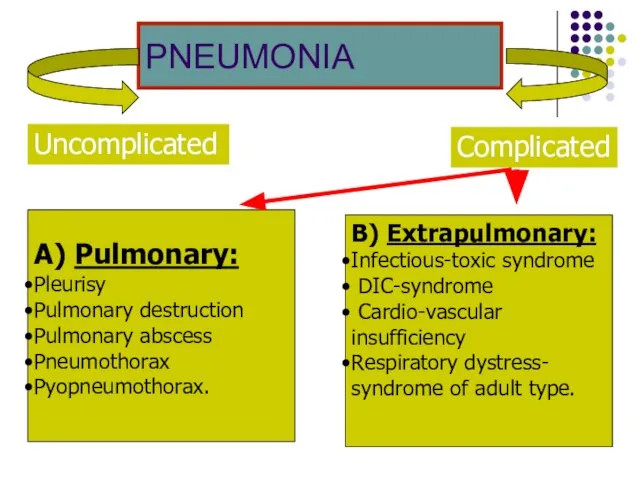

- 20. PNEUMONIA Complicated Uncomplicated А) Pulmonary: Pleurisy Pulmonary destruction Pulmonary abscess Pneumothorax Pyopneumothorax. B) Extrapulmonary: Infectious-toxic syndrome

- 21. Clinical symptoms

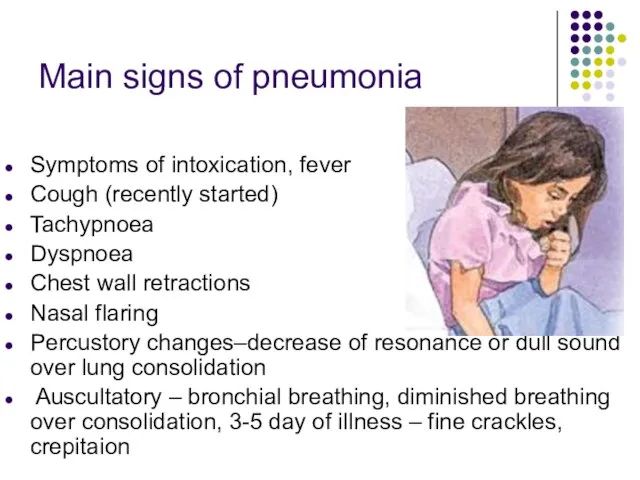

- 22. Main signs of pneumonia Symptoms of intoxication, fever Cough (recently started) Tachypnoea Dyspnoea Chest wall retractions

- 23. Pneumonia indications in children younger 5 years of age: Nasal flaring (before 12 months) Oxygen saturation

- 24. Clinical symptoms Newborn and neonates present with: Grunting Poor feeding Irritability or lethargy Tachypnoea sometimes Fever

- 25. Clinical symptoms Infants present with: Cough (the most common symptom after the first four weeks) Tachypnoea

- 26. Clinical symptoms Toddlers/pre-school children: Again, preceding URTI is common Cough is the most common symptom Fever

- 27. Clinical symptoms Older children: There will be additional symptoms to those above More expressive and articulate

- 28. Criteria for Respiratory Distress in Children With Pneumonia Tachypnea: RR breaths/minute >50 for age 3–11 months

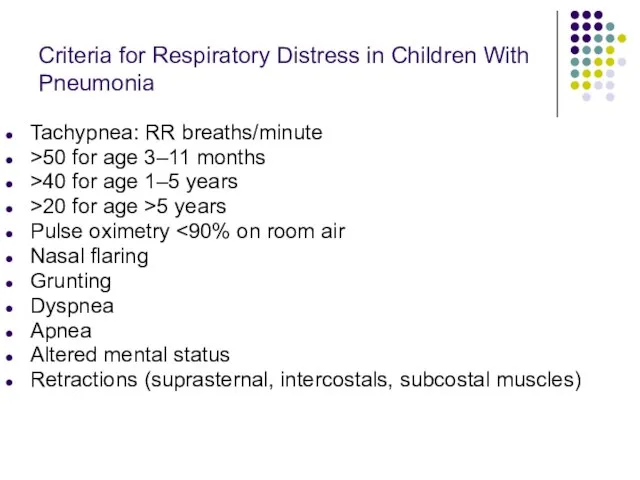

- 29. Criteria for CAP Severity of illness Major criteria Invasive mechanical ventilation Fluid refractory shock Acute need

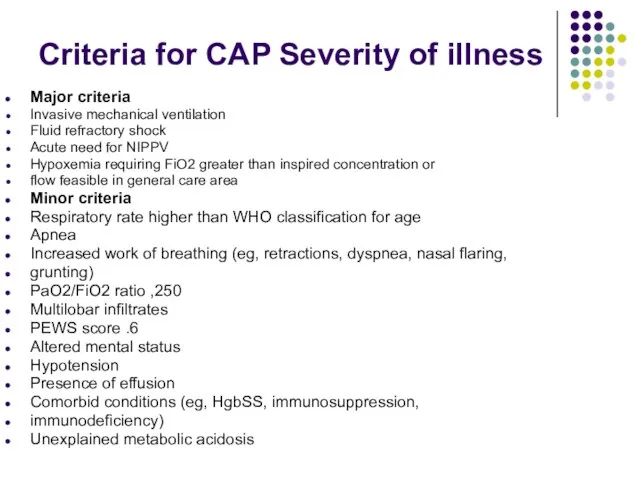

- 30. Percussion & auscultation Local physical signs of pneumonia (shortening of percussion sound in the zone of

- 31. X-ray study Pneumonia diagnosis always includes detecting patchy infiltrative changes in the lung parenchyma with other

- 32. X-ray study used If the diagnosis is questionable This is repeated episode The patient is ill

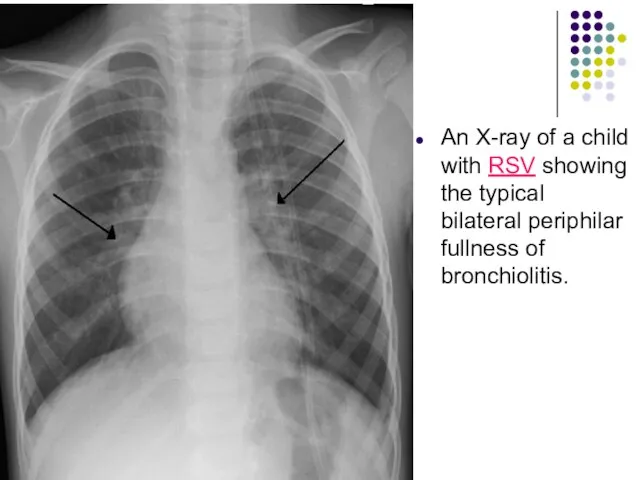

- 33. An X-ray of a child with RSV showing the typical bilateral periphilar fullness of bronchiolitis.

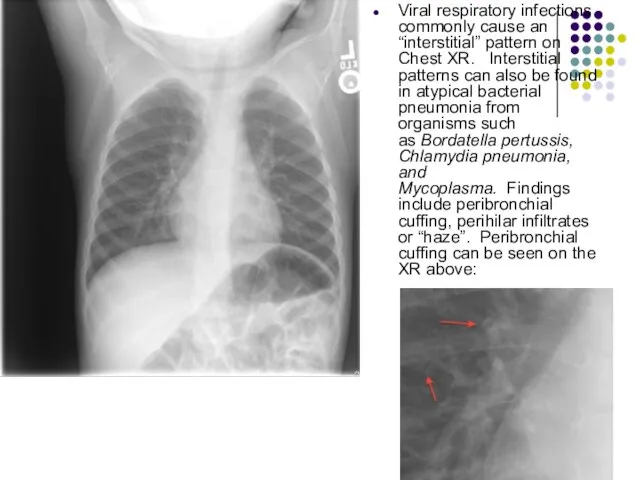

- 34. Viral respiratory infections commonly cause an “interstitial” pattern on Chest XR. Interstitial patterns can also be

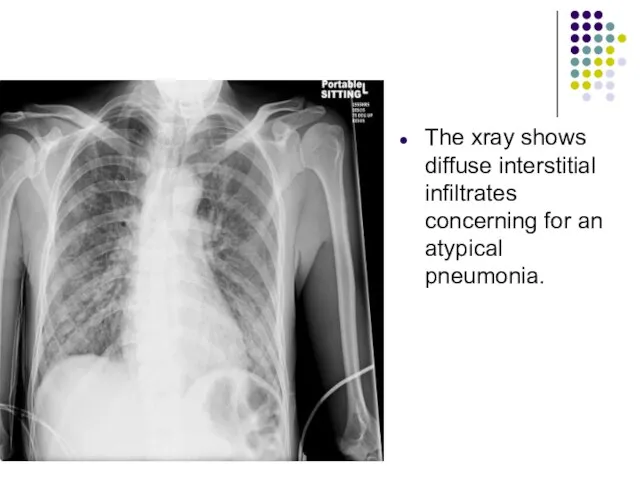

- 35. The xray shows diffuse interstitial infiltrates concerning for an atypical pneumonia.

- 36. Round focus of consolidation in the left upper lobe. Pneumonia. Round focus of consolidation in the

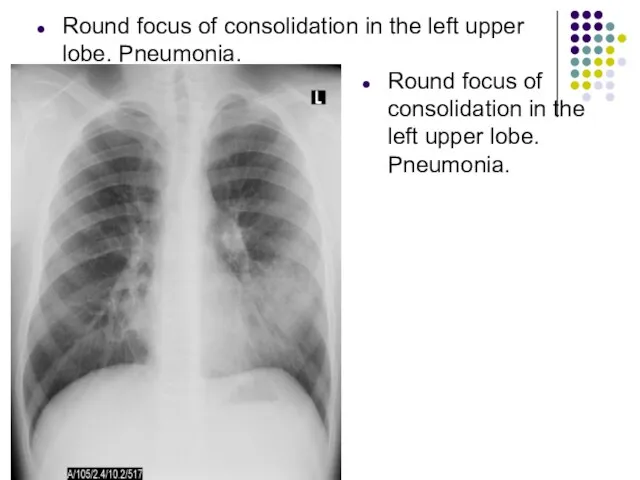

- 37. Alveolar consolidations in the left lower lobe and in the right lower lobe. Mycoplasma pneumoniaepneumonia

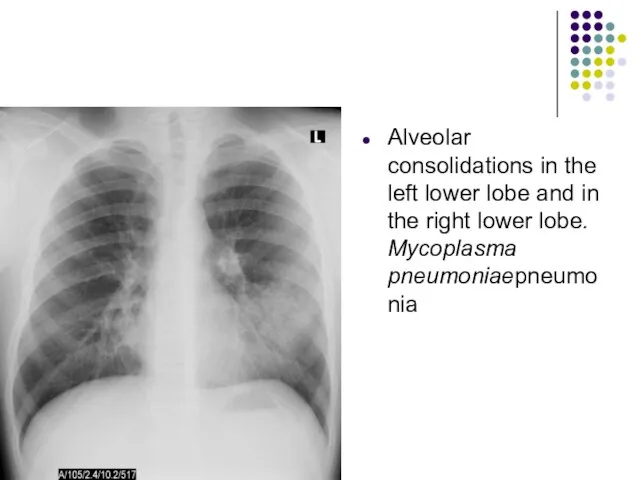

- 38. Lobar pneumonia in a 5 year old child

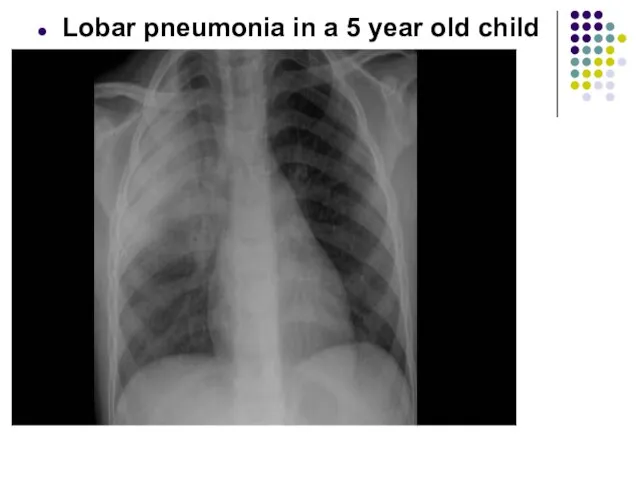

- 39. Pulmonary abscess. Pulmonary abscess.

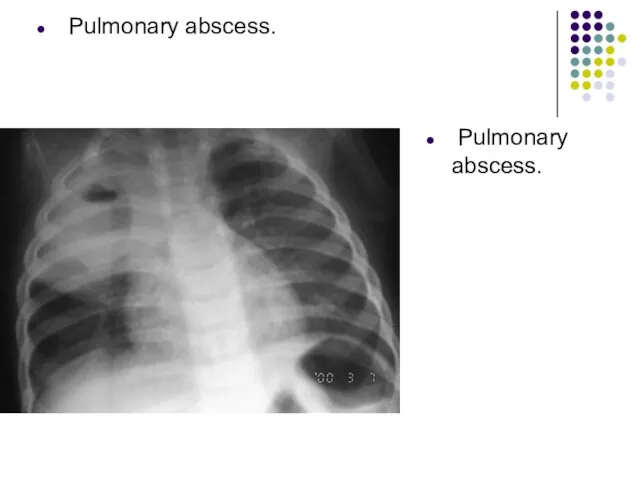

- 40. Abscess of right lung.

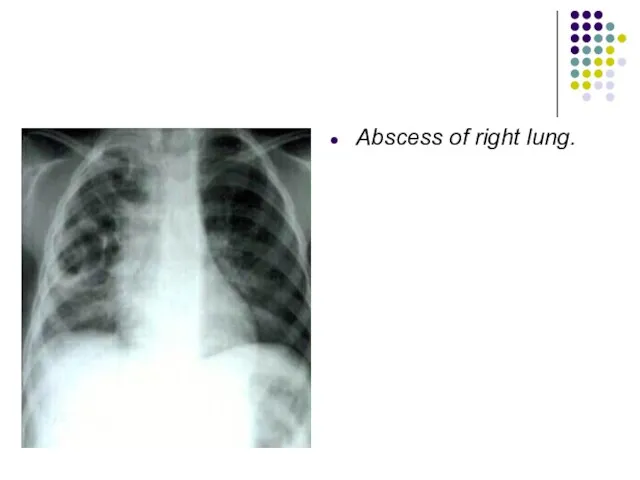

- 41. Sputum Gram Stain and Culture Sputum is rarely produced in children younger than 10 years, and

- 42. Rapid antigen tests are available for RSV, parainfluenza 1, 2, and 3, influenza A and B,

- 43. Serologic testing for IgM or an increase in IgG titers may be performed for Mycoplasma and

- 44. The complete blood count Complete Blood Cell Count may help in determining if an infection is

- 45. Acute-phase reactants erythrocytesedimentation rate (ESR) C-reactive protein (CRP)concentration serum procalcitonin concentration

- 46. Oxygen saturation should be assessed by pulse oximetry in children with respiratory distress, significant tachypnea, or

- 47. Classification of hypoxaemia There are two ways of classifying hypoxaemia in children: (i) WHO classification and

- 48. Clinical picture of focal pneumonia In children of pre-school and school age: Respiratory complaints, symptoms of

- 50. Clinical picture of segmental pneumonia: First variant: -course is favourable, sometimes they aren’t diagnosed because local

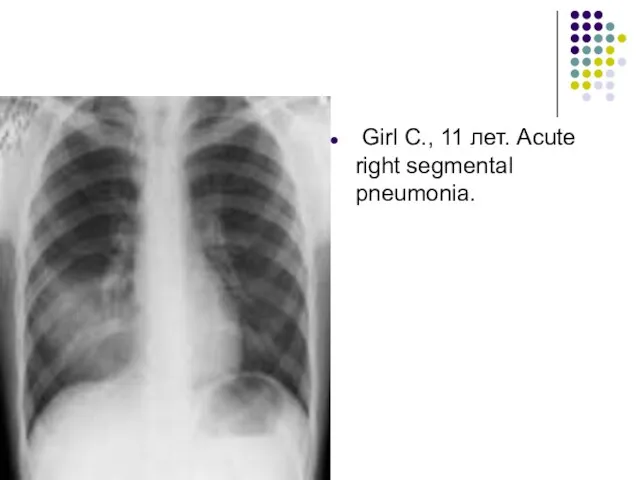

- 51. Girl С., 11 лет. Acute right segmental pneumonia.

- 52. Clinical picture of segmental pneumonia: Second variant: -similar to clinical picture of croupous pneumonia with abrupt

- 53. Clinical picture of croupous pneumonia Onset is abrupt, temperature 39-40°, headache, severe disorders of general condition,

- 54. Mycoplasma pneumoniae Vague and slow-onset history over a few days or weeks of constitutional upset, fever,

- 55. Chlamydophila pneumoniae Gradual onset, which may show improvement before worsening again; incubation period is 3-4 weeks.Initial

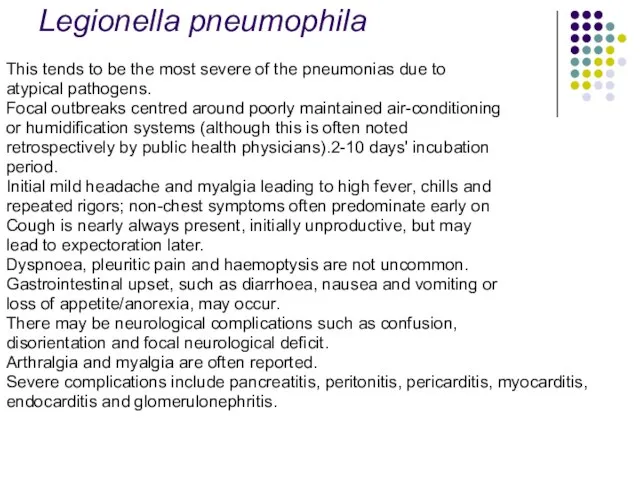

- 56. Legionella pneumophila This tends to be the most severe of the pneumonias due to atypical pathogens.

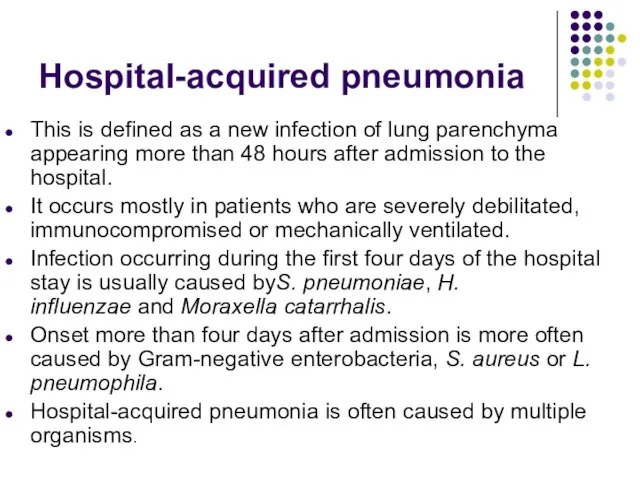

- 57. Hospital-acquired pneumonia This is defined as a new infection of lung parenchyma appearing more than 48

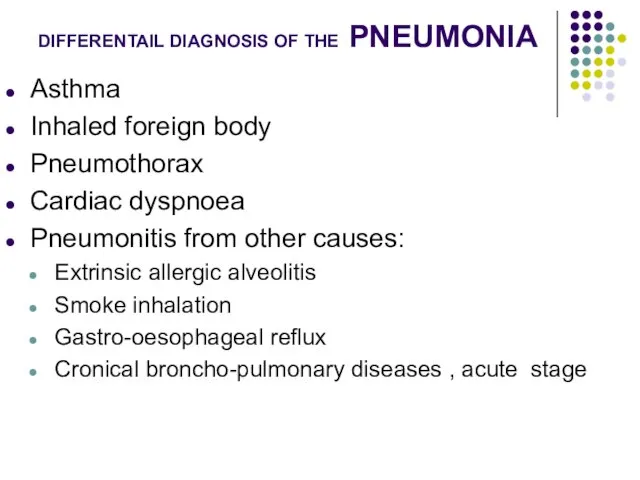

- 58. DIFFERENTAIL DIAGNOSIS OF THE PNEUMONIA Asthma Inhaled foreign body Pneumothorax Cardiac dyspnoea Pneumonitis from other causes:

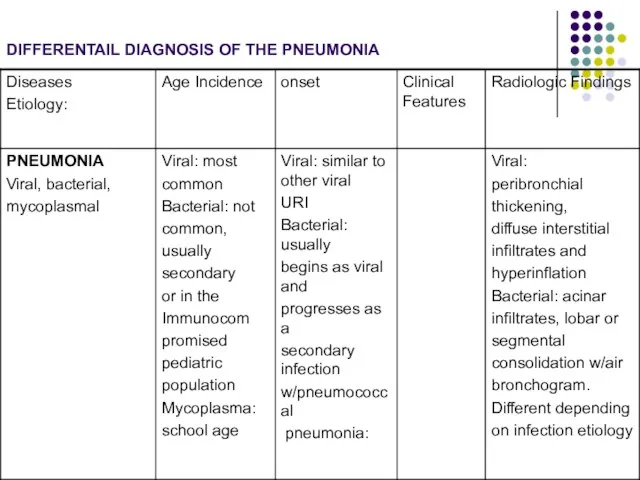

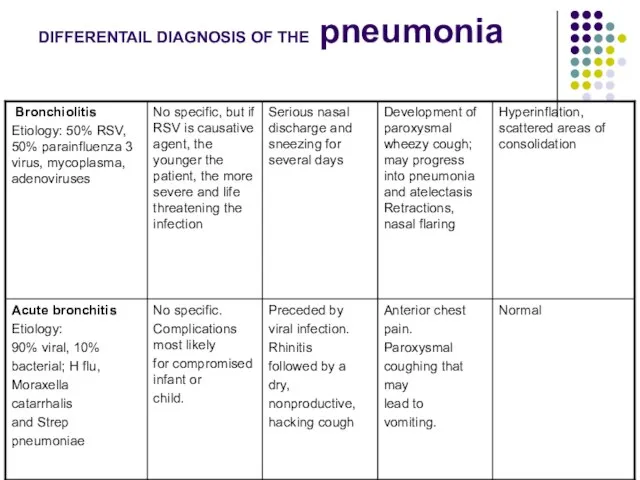

- 59. DIFFERENTAIL DIAGNOSIS OF THE PNEUMONIA

- 60. DIFFERENTAIL DIAGNOSIS OF THE pneumonia

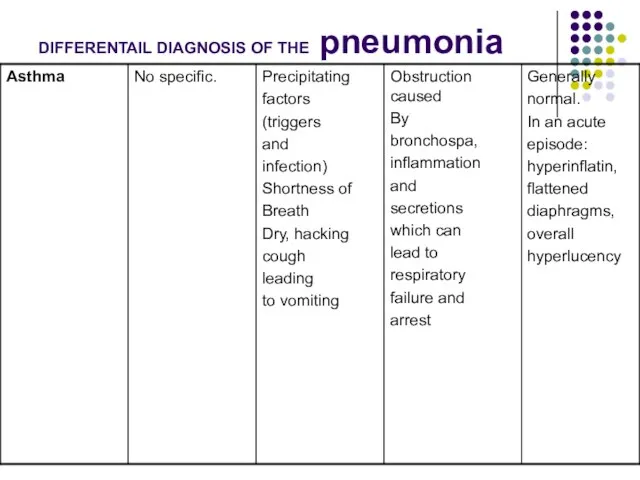

- 61. DIFFERENTAIL DIAGNOSIS OF THE pneumonia

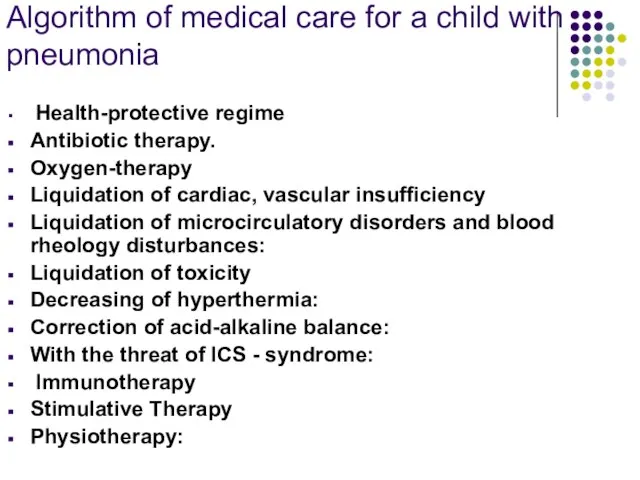

- 62. Algorithm of medical care for a child with pneumonia Health-protective regime Antibiotic therapy. Oxygen-therapy Liquidation of

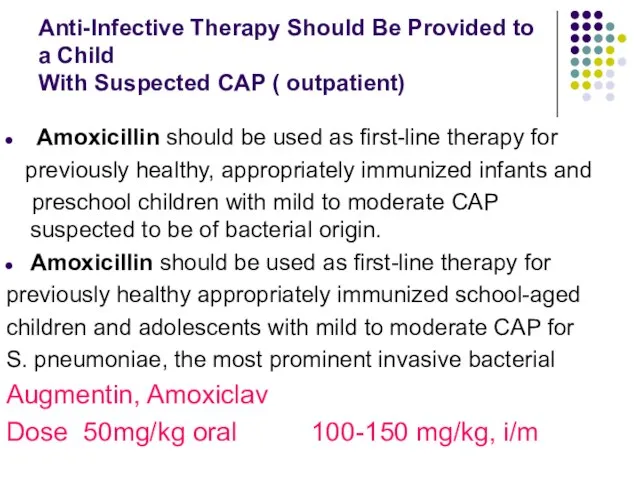

- 63. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( outpatient) Amoxicillin should be

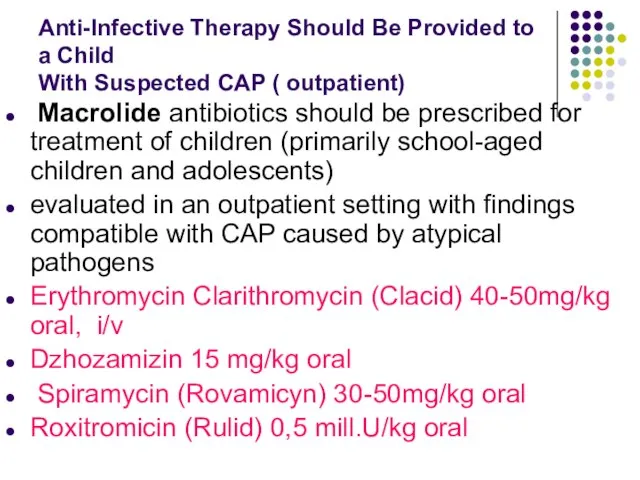

- 64. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( outpatient) Macrolide antibiotics should

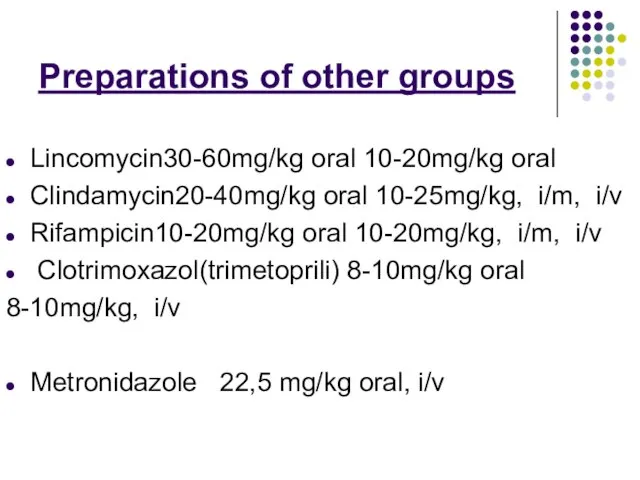

- 65. Preparations of other groups Lincomycin30-60mg/kg oral 10-20mg/kg oral Clindamycin20-40mg/kg oral 10-25mg/kg, i/m, i/v Rifampicin10-20mg/kg oral 10-20mg/kg,

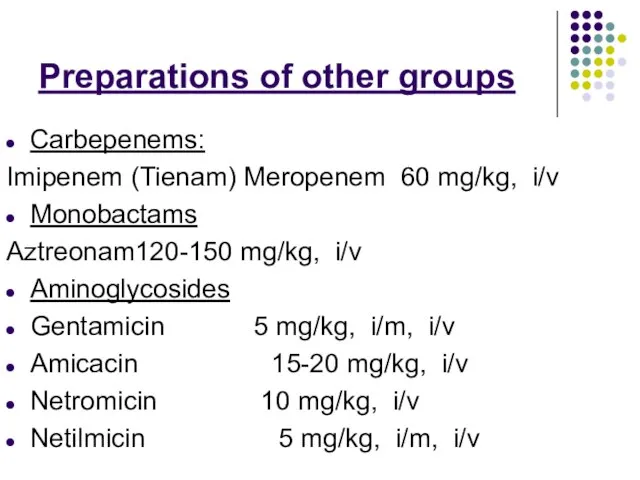

- 66. Preparations of other groups Carbepenems: Imipenem (Tienam) Meropenem 60 mg/kg, i/v Monobactams Aztreonam120-150 mg/kg, i/v Aminoglycosides

- 67. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( outpatient) Influenza antiviral therapy

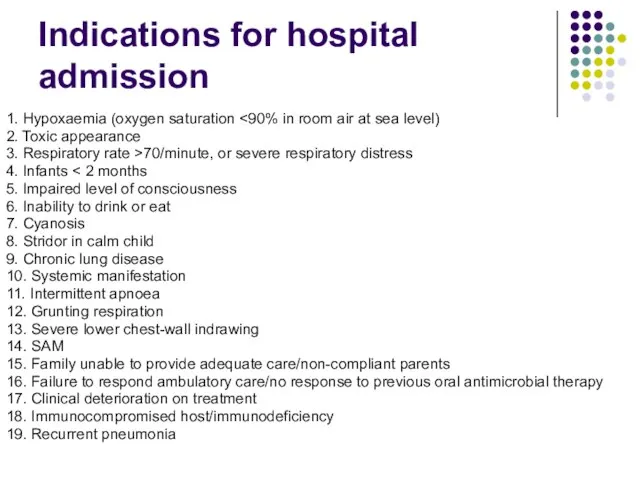

- 68. Indications for hospital admission 1. Hypoxaemia (oxygen saturation 2. Toxic appearance 3. Respiratory rate >70/minute, or

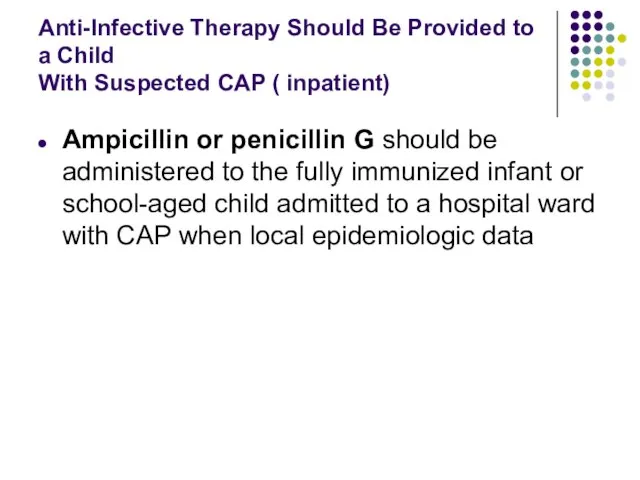

- 69. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( inpatient) Ampicillin or penicillin

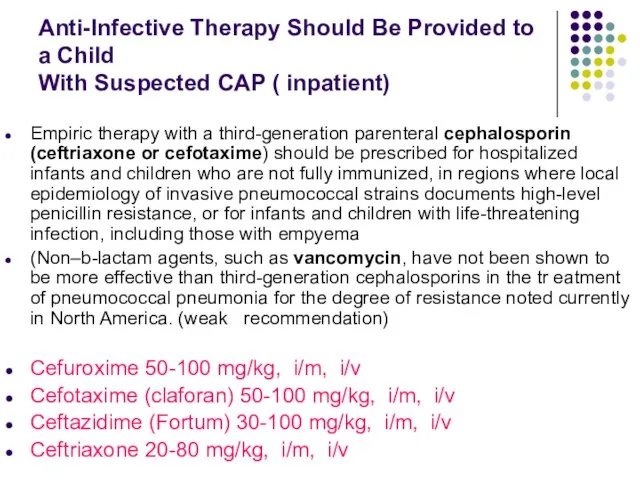

- 70. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( inpatient) Empiric therapy with

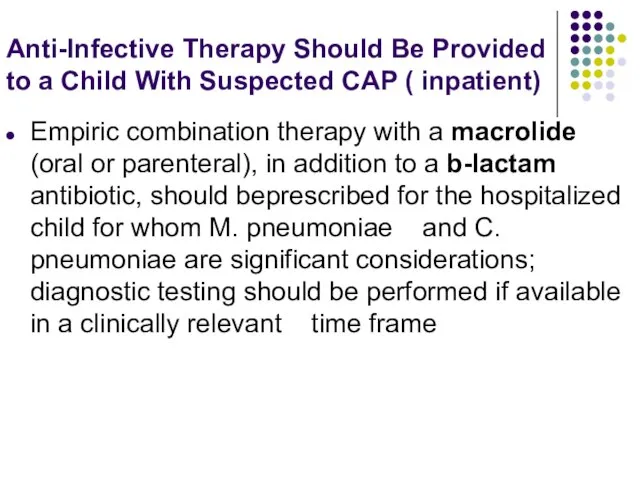

- 71. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( inpatient) Empiric combination therapy

- 72. Anti-Infective Therapy Should Be Provided to a Child With Suspected CAP ( inpatient) Vancomycin or clindamycin

- 73. Management of atypical pneumonia Macrolides, such as erythromycin, clarithromycin and azithromycin, have been shown to be

- 74. Indications for oxygen therapy 1. Hypoxaemia (oxygen saturation 2. Central cyanosis 3. Severe lower chest-wall in-drawing

- 75. oxygen therapy a) To ensure free airway, optimization of ventilation (throwing head back, the output of

- 76. Methods of oxygen administration Nasal prongs: are recommended for most children. Nasal prongs give a maximum

- 77. Methods of oxygen administration Headbox: oxygen is well tolerated by young infants. Headbox oxygen requires no

- 78. Antipyretics and analgesics drugs Children with CAP are generally pyrexial and may also have some pain,

- 79. Indications for the use of antipyretics and analgesics in CAP Rectal temperature >39 Celsius There is

- 80. Antipyretics and analgesics drugs The most appropriate agent is paracetamol at a dose of 15 mg/kg/dose

- 81. Liquidation of cardiac, vascular insufficiency strophanthin– 0,05% for children till 1 y.o. 0,1-0,15 ml 1-2 time

- 82. Acute vascular insufficiency Stream i/V prednsolon 2 mg/ kg or hydrocortison 10-15 mg /kg I/V plasma

- 83. Sudden (acute) pulmonary edema symptoms Extreme shortness of breath or difficulty breathing (dyspnea) that worsens when

- 84. Prevention of lung edema oxygen therapy use antifoam drugs (inhalation 30 % C2H5OH 30 - 40

- 85. Anticonvulsion therapy Deacresing hypoxia and Deacresing edema of brain Furosemid i/v 2-3 mg/kg Deacresing excitability –0,5

- 86. Liquidation of toxicity: albumin, plasma, Haemodesum 5-10 ml/kg/day. Correction of acid-alkaline balance: 4% solution of sodium

- 87. Intravenous fluids Intravenous fluids must be used with great care and with caution, and only if

- 88. Indications for I/V fluid Shock Inability to tolerate enteral feeds Sepsis Severe dehydration Gross electrolyte imbalance

- 89. Calorie requirements Adequate nutrition is of particular concern, especially when there are underlying factors such as

- 90. Enteral feeds Children with pneumonia should be encouraged to feed orally unless there are indications for

- 91. Chest physiotherapy postural drainage, percussion of the chest deep breathing exercises should be routinely performed in

- 92. Apparatus physiotherapy during the acute clinical manifestations of acute pneumonia is contrindicated. With the normalization of

- 93. Mucolytic agents Anti-tussive remedies are not recommended as they cause suppression of cough and interfere with

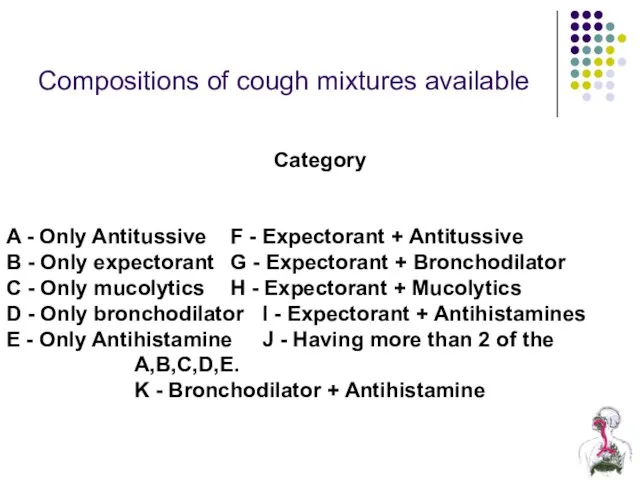

- 94. Compositions of cough mixtures available Category A - Only Antitussive F - Expectorant + Antitussive B

- 95. Postural drainage: There is no evidence for the use of a head-down position for postural drainage.

- 96. Electrophoresis

- 97. Ultraviolet irradiation therapy

- 98. Apparatus for UHF-therapy «UHF 30-2» The apparatus is intended for therapeutic effect on the patient by

- 99. Single-channel laser therapy apparatus that generates the red and infrared radiation, with an open modular system

- 100. Ultrasound therapy apparatus BTL-4710 Sono Professional

- 101. Complication of pneumonia

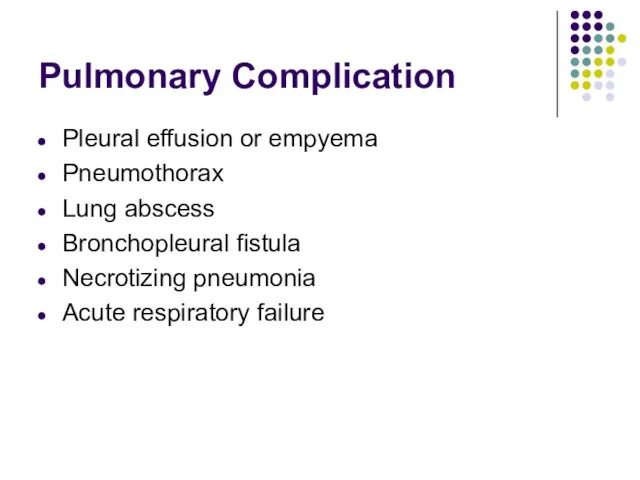

- 102. Pulmonary Complication Pleural effusion or empyema Pneumothorax Lung abscess Bronchopleural fistula Necrotizing pneumonia Acute respiratory failure

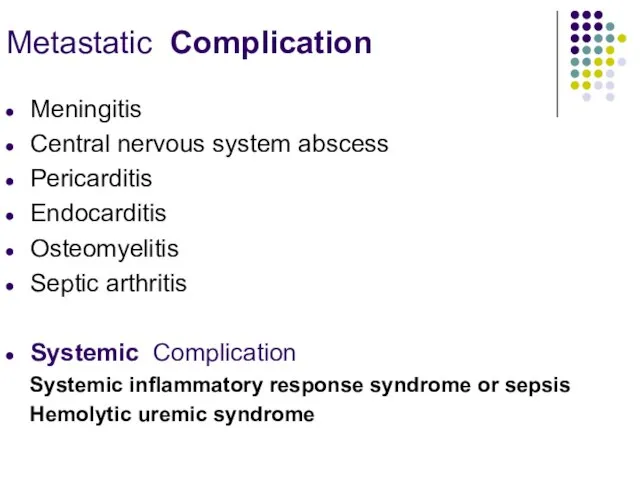

- 103. Metastatic Complication Meningitis Central nervous system abscess Pericarditis Endocarditis Osteomyelitis Septic arthritis Systemic Complication Systemic inflammatory

- 105. Скачать презентацию

Презентация на тему Рынок труда и заработная плата

Презентация на тему Рынок труда и заработная плата Мы начинаем КВМ

Мы начинаем КВМ Советы олимпиаднику

Советы олимпиаднику Произведения искусства. Викторина

Произведения искусства. Викторина Презентация на тему: Петр Великий русской литературы 10 класс

Презентация на тему: Петр Великий русской литературы 10 класс Порядок учета залогового имущества и возмещения требований путем реализации залогового имущества

Порядок учета залогового имущества и возмещения требований путем реализации залогового имущества «Мой классный - самый классный»

«Мой классный - самый классный» А.С.Пушкин

А.С.Пушкин Наша бібліотека

Наша бібліотека Дрожжин Спиридон Дмитриевич

Дрожжин Спиридон Дмитриевич VII Всероссийский конкурс учебно-исследовательских экологических проектов «Человек на Земле» Номинация №1Название проекта: «Из

VII Всероссийский конкурс учебно-исследовательских экологических проектов «Человек на Земле» Номинация №1Название проекта: «Из Презентация на тему Ткани животных

Презентация на тему Ткани животных Отечественная война 1812

Отечественная война 1812 Развитие выносливости у школьников среднего возраста по средствам легкой атлетики

Развитие выносливости у школьников среднего возраста по средствам легкой атлетики Проблема исторического выбора

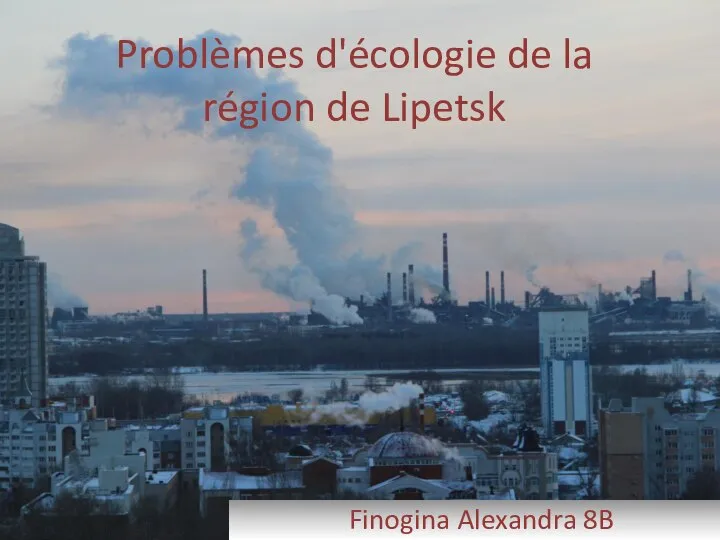

Проблема исторического выбора Problèmes d'écologie de la région de Lipetsk

Problèmes d'écologie de la région de Lipetsk Комплексный подход или «деньги на ветер»?

Комплексный подход или «деньги на ветер»? Буквы К, к, обозначающие согласные звуки [к], [к`]

Буквы К, к, обозначающие согласные звуки [к], [к`] Сельское хозяйство и окружающая среда

Сельское хозяйство и окружающая среда Психологический портерет Чарльза Буковски

Психологический портерет Чарльза Буковски Моя любимая Россия. Викторина

Моя любимая Россия. Викторина Судебный процесс и судопроизводство Франции

Судебный процесс и судопроизводство Франции Презентация на тему Обратная пропорциональность (8 класс)

Презентация на тему Обратная пропорциональность (8 класс) Традиционная глиняная игрушка Орловского края. Работы учащихся

Традиционная глиняная игрушка Орловского края. Работы учащихся Моя малая Родина - посёлок 1 Мая

Моя малая Родина - посёлок 1 Мая Муравьишка

Муравьишка Драматургическая схема построения материала

Драматургическая схема построения материала Бренди мира

Бренди мира