Слайд 2PROJECT PLAN

RULER FOR THE THRONE OF MUSCOVY

FOREIGN POLICY AND WAR

INTERNAL AFFAIRS AND

THE SMOLENSK WAR

THE FINAL YEARS

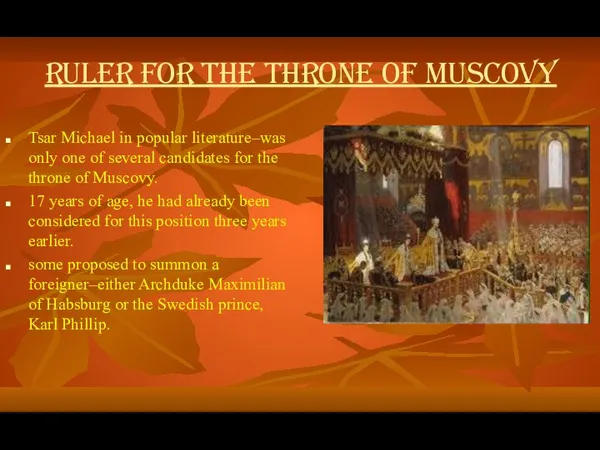

Слайд 3RULER FOR THE THRONE OF MUSCOVY

Tsar Michael in popular literature–was only

one of several candidates for the throne of Muscovy.

17 years of age, he had already been considered for this position three years earlier.

some proposed to summon a foreigner–either Archduke Maximilian of Habsburg or the Swedish prince, Karl Phillip.

Слайд 4THE CHOSSEN CANDIDAT

There was strong preference to choose a Russian candidate. Rivalry

among candidates eventually eliminated all but the young Romanov, widely regarded as a surrogate for his father Filaret. The latter’s martyr‑like captivity, in fact, contributed to his son’s election.

The electoral assembly of 700 delegates was initially unable to reach a consensus.

But on 21 February 1613 finally Michael be chosen as the compromise candidate.

Слайд 5FOREIGN POLICY AND WAR

THE ACCOMPLISHMENTS BEFORE FILARET’S RETURN

The primary task was

to equip an army to fight the Swedes and Poles; because of the economic destruction and stolen bands of peasants & Cossacks, proved extremely difficult to raise the funds.

To obtain the needed levies, Michael ordered some‘councils of the realm’ which was unissued.

The government used information of economic conditions in the provinces to impose taxes–normally 5 %, sometimes to 10 %, of the property value and the business turnover. Also, forced the richest merchants to make contributions and loans.

By 1618 the government had raised seven special levies to cut a budget loss that, had run over 340,000 roubles.

Слайд 6RELATIONS WITH POLAND‑LITHUANIA

They were more difficult.

Poles declined to recognize Michael and Russians

refused to accept Władysław as tsar.

After mediation collapsed Poles launched a new military offensive and were able to attack Moscow.

Two sides agreed to an armistice of fourteen and a half years: both were exhausted from the conflict, the Polish Sejm denied more funds, and Moscow fervently wanted an exchange of prisoners. The armistice, signed in the village of Deulino compelled Moscow to renounce its claim to west Russian areas.

Слайд 7Internal affairs and the Smolensk war

After his return in 1619, Filaret became

the patriarch of Moscow.

The world now seemed to be in order, even in the relations between father and son.

the government faced serious problems; in addition to seeking vengeance on Poland.

Filaret had to address the question of tax reform. To finance the Streltsy.

In 1614, the government already imposed some new special levies–‘Streltsy money’ from townspeople and ‘Streltsy grain’ from peasants.

Слайд 8Internal affairs and the Smolensk war

The government also increased the ‘postal money’,

the largest regular tax.

Because of the principle of collective responsibility (krugovaia poruka ).

Those who remained behind had to assume the obligations of the bondsmen and thus pay even higher taxes.

Слайд 9Internal affairs and the Smolensk war

Ever since 1584 the government had periodically

prohibited this form of tax evasion, but with scant effect.

Filaret also failed to achieve a satisfactory solution.

Patriarchate owned approximately a thousand plots of land in Moscow.

More successful in the long run was the gradual conversion of the tax base from land to household, a process that commenced in the 1620s but only reached completion in 1679.

Filaret’s policy towards towns was still less successful.

Слайд 10The final years

The war drew Muscovy even closer to the West.

Besides the Troops of the New Order (temporarily disbanded for lack of funds).

The most tangible sign of Europeanization was the influx of Western merchants and entrepreneurs.

Dominance shifted from the English to the Dutch: Andries Winius obtained monopoly rights to construct ironworks in the towns of Tula and Serpukhov (the first blast furnace began operations in 1637)

The Walloon Coyet established the first glass plant in the environs of Moscow.

Слайд 11THE FINAL YEARS

The Orthodox Church was able to contain Western influence in

cultural matters.

The main spiritual influence, instead, came from Ukraine

–for example, a proposal in 1640.

The metropolitan of Kiev, Petr Mohyla, to establish an ecclesiastical academy in Moscow.

The Church also denounced as ‘heresy’ the correction of church books, which had commenced in 1618.

In foreign affairs too the tsar had to make a difficult decision.

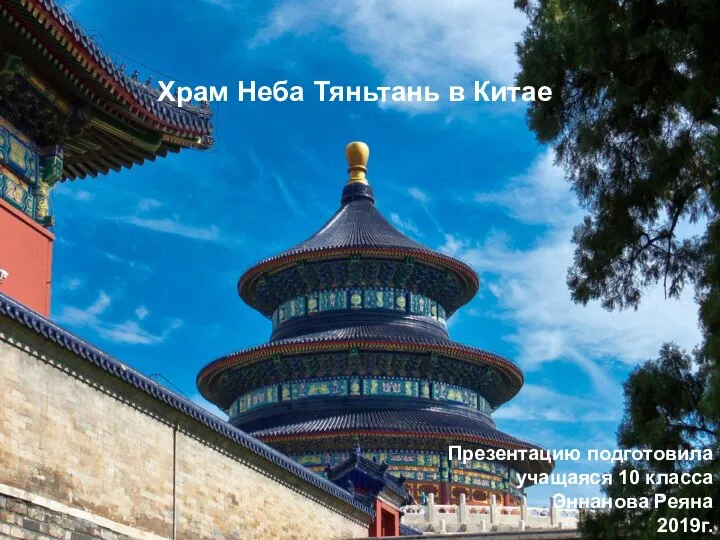

Храм Неба Тяньтань в Китае

Храм Неба Тяньтань в Китае Презентация на тему Каменная летопись города

Презентация на тему Каменная летопись города  Парк “Сокольники”

Парк “Сокольники” Мы помним, мы гордимся. Мой герой

Мы помним, мы гордимся. Мой герой Герои Великой Отечественной войны

Герои Великой Отечественной войны История в камне

История в камне 18 сентября 2008 года Президент Российской Федерации Д.А. Медведев подписал Указ «О проведении в 2009 году в Российской Федерации Года молодёжи». Как отмечается в Указе, одной из главных задач является «…воспитание патриотизма и гражданской ответственност

18 сентября 2008 года Президент Российской Федерации Д.А. Медведев подписал Указ «О проведении в 2009 году в Российской Федерации Года молодёжи». Как отмечается в Указе, одной из главных задач является «…воспитание патриотизма и гражданской ответственност Засуха в 1974-1975 годы в селе Усть-Уйском

Засуха в 1974-1975 годы в селе Усть-Уйском Золотое кольцо России

Золотое кольцо России Презентация на тему Германская империя

Презентация на тему Германская империя  По следам ондозерского десанта

По следам ондозерского десанта Казахстан в годы ВОВ

Казахстан в годы ВОВ Великая Отечественная война

Великая Отечественная война Музей солнца

Музей солнца Богатыри земли русской

Богатыри земли русской Послевоенная архитектура Донбасса

Послевоенная архитектура Донбасса Гражданская война и интервенция

Гражданская война и интервенция Екатерина II (1762-1796)

Екатерина II (1762-1796) Історія України 11 клас 18.10.22

Історія України 11 клас 18.10.22 Внешняя политика России в XVII в Мартынова Светлана Вячеславовна учитель истории МОУ СОШ №1 г. Камешково

Внешняя политика России в XVII в Мартынова Светлана Вячеславовна учитель истории МОУ СОШ №1 г. Камешково Изготовление резиномоторной машины

Изготовление резиномоторной машины Борьба Руси с иноземными нашествиями в XIII в. восток и запад

Борьба Руси с иноземными нашествиями в XIII в. восток и запад Социально-экономическое развитие страны

Социально-экономическое развитие страны Труженики тыла- незаметные герои войны

Труженики тыла- незаметные герои войны Наши деды – славные победы

Наши деды – славные победы Куликовская битва 1380 г

Куликовская битва 1380 г 80 лет со дня начала блокады Ленинграда (8 сентября 1941 -27 января 1944гг.)

80 лет со дня начала блокады Ленинграда (8 сентября 1941 -27 января 1944гг.) Политика военного коммунизма в годы гражданкой войны. Казахстан. (9 класс)

Политика военного коммунизма в годы гражданкой войны. Казахстан. (9 класс)