Слайд 2

For better or worse, Russia inherited from the former Soviet Union a

rich tapestry of military thought. This body of political and military thinking was grounded in Soviet historical experience and connected to the ideological prism through which the Communist Party of the Soviet Union saw the world1. Among the more important taskings for the Soviet military from the end of the Second World War until the collapse of Lenin’s experiment in 1991 was the avoidance of a decisive surprise attack in the first phase or “initial period” of war. A repeat of the disastrous Soviet experience against the German Wehrmacht in the early stages of Operation Barbarossa, Hitler’s invasion of Russia in June, 1941, could not be tolerated. Soviet military theorists also wrestled later with the problem of avoiding defeat and ensuring victory in the initial period of war under Cold War conditions: bipolarity, and the availability of nuclear weapons to the U.S., NATO and Soviet militaries.

Слайд 3

Russia now faces a NATO coalition that has pushed its former Cold

War borders eastward by a thousand miles, creating buffer zones between NATO and Russia and facing a declining post-Soviet military. NATO avers that all of this is nonthreatening to Russia and invites Russia to the table of cooperative security in post-Cold War Europe. Despite an improved post-Cold War political climate for Russian – American and NATO – Russian relations, Russia’s conventional military weakness encourages it to plan for an initial period of war with first or early nuclear use – if not in Europe, then perhaps elsewhere. Russia’s problem of controlling nuclear escalation in the initial period of war is no less a serious matter now than it was for the late Cold War Soviets, but with the important difference that Russia, not NATO, is now nuclear dependent and NATO benefits from high technology conventional superiority. Further, the possible use of information weapons by Russia or its opponents in the early stages of a war or even during a crisis could speed up time pressures and accelerate psychological stresses for policy makers and their military advisors.

Слайд 4

Russian military historians have carefully studied the period of time from the

commencement of hostilities until friendly forces are within grasp of their initial operational and strategic military objectives. Military historians refer to this expanse of time as the “initial period of war”2. The authoritative study by General of the Army S. P. Ivanov on this subject published in 1974 was part of a broader interest within the Soviet military establishment in the problem of threat assessment and the avoidance of surprise attack3. Having turned away from the one variant war model of the Khrushchev years, Soviet military planners reviewed their World War II experience with regard to strategic operations conducted by several fronts in a continental theater of operations on a strategic scale4. Those studies revealed the strengths and the weaknesses of the Soviet conduct of campaigns at the operational and operational‑strategic levels in the early period of the war and subsequently. Future Soviet commanders would have to apply those lessons to a different technology and policy context after World War II Special account would have to be taken of the "revolution in military affairs" that had been brought about by the development and deployment of nuclear weapons

Слайд 5According to Lieutenant General M. M. Kir'ian, the initial period of war

is “the time during which the belligerents fought with previously deployed groupings of armed forces to achieve the immediate tactical goals or to create advantageous conditions for committing the main forces to battle and for conducting subsequent operations”6. Major General M. Cherednichenko noted in a 1961 article that prior to the Second World War, the initial period of war was defined in Soviet military theory according to World War I experience. This meant, according to Cherednichenko, the period from the official declaration of war and the start of social mobilization to the beginning of main battle force engagements7. Soviet planners, following this model, assumed that covering forces deployed in the border military districts were to fight the first phases of the defensive battle. Their mission was to cause attrition to enemy forces and to delay the enemy advance until the Soviet second echelon forces counterattacked. However, during the interwar years the widespread introduction into the armed forces of tanks, aviation and other means of armed conflict “revealed a strong possibility of surprise offensives and the achievement of decisive aims at the beginning of wa

Слайд 6

Kir'yan's article in the June 1988 Military-Historical Journal notes that Soviet military theory during

the 1930s taught that a surprise attack with premobilized forces could 'give the expected results only against a small state' and that, for an offensive against the Soviet Union, a definite time of mobilization, concentration and deployment of the German main forces would be required9. Soviet military analysts have charged the political and armed forces leadership on the eve of war with errors in addition to theoretical ones. Failures in the assessment of warning intelligence and the reluctance of the political leadership even to take sensible preparatory measures in the western border districts of the USSR allowed Soviet defenders to fall below adequate standards for readiness. This indictment of the Soviet armed forces High Command and of Stalin personally was offered by A. M. Nekrich in his classic 1941 22 lunia (22 June 1941)

Слайд 7

Studies by Western specialists on the Soviet armed forces have supported much

of Nekrich's verdict, if not all of his analysis in detail. John Erickson has noted the effects on the proficiency of Soviet command, in the early stages of World War II, of Stalin's purges of the armed forces' leadership from 1937-193911. Much of the prewar theory of deep operations and mechanized‑motorized warfare which had been pioneered in Soviet professional military writing of the 1920s and 1930s was forgotten in the aftermath of the military purges and had to be relearned in the hasty reorganization of Soviet defenses after 22 June 1941. Misinterpretation of the experience of the Spanish Civil War by the Soviet post-purge armed forces leadership created a hiatus with regard to the development of theory and force structure for large-scale offensive and defensive operations. Only after bitter disappointments in their war against Finland, and after having observed the successes of the Germans against Poland and France, did the Soviet High Command turn to the practical re-equipping and retraining of the armed forces for large-scale, mobile offensive and defensive operations. Unfortunately for the Soviets, they were caught in the midst of reorganization and re-equipment, and their concepts of the strategic defensive had not been carefully thought out

Слайд 8Another aspect of Soviet preparedness for war was how well the General

Staff of the Soviet armed forces understood the operational doctrines of potential opponents13. Intelligence must not only convey adequate “order of battle” data and indications of hostile intent. It must also establish how the opponent is going to fight if it comes to that. As Richard K. Betts and other experts on intelligence have pointed out, there is a great deal of difference between adequacy of warning and effectiveness of response14. In between warning and response is the psychologically based but intelligence driven 'threat perception', which is highly subjective. Part of this threat perception is the military operational doctrine according to which war plans will be carried out. For example, it makes a great deal of difference to potential defenders whether the opponent's strategy is one of Blitzkrieg or of a slow war of attrition15. Or, in nuclear strategy, it may matter whether selective and limited attacks are planned in the initial phases of a superpower conflict, and regardless of whether the actual outcome of such a war is judged to be “winnable” by either side. Deterrence may be affected by the expectations held by American or Soviet leaders about the willingness of either state to respond to limited attacks by selective rather than general retaliation

Слайд 9

The Soviet experience with Barbarossa taught two things which were not necessarily contradictory, but

which had the potential to create significant trade-offs in commitments of intelligence and planning assets. The first lesson, openly acknowledged by Soviet commentators for many years, was that operational defeats on a large scale could be inflicted by the side that pre‑mobilized sufficient forces and means and successfully executed a deception plan. The second lesson was that operational surprise, even on a large scale, did not necessarily equate to strategic victory. Soviet experience with Hitler's surprise offensive taught that wars can also be protracted, and that attackers whose operative constructs are based on victory in the initial period can overreach. The judgment of some Soviet military theorists of the 1920s and 1930s, of skepticism that wars could be won in their initial period against territorially large and well‑armed defenders, was not totally disproved by the events of World War II. Hitler's Blitzkrieg defeated the Poles and French, but not the Soviet Union. However, the French cannot be counted among the smaller and weaker adversaries of Hitler, regardless of the degree to which Poland was outmatched against the Wehrmacht (and politically scissored by the Nazi-Soviet non-aggression pact). Therefore, under the right conditions surprise, combined with effective weight of blow, can prove strategically, as well as operationally and tactically, decisive

Слайд 10

It therefore seemed prudent to assume, on the basis of these lessons,

that in future wars the initial period could be decisive. Nuclear weapons made the potential decisiveness of the initial period of war even more of a two-sided die than it was before the nuclear era. Larger losses could be inflicted by a surprise attacker against an unprepared defender. However, if both sides were armed with nuclear weapons, then the defender might retaliate against the attacker, imposing unacceptable losses. Further, this two‑sided problem, of greater attacker and defender vulnerabilities, could be posed by modern, high‑technology conventional weapons. Thus, from the perspective of Soviet intelligence estimators and military planners, NATO modernization plans of the latter 1970s and 1980s presented an initial period of war in which the temptation of opportunity for surprise attack had to be traded off against the possibility of catastrophic failure. In the present century, an enlarged NATO, supported by an enhanced information-based capability for long range precision strike and network-centric warfare, poses for conservative Russian military planners the necessity for nuclear first use to avoid otherwise inevitable defeat in the initial period of a large scale war fought near or in Russia’s western territory

Слайд 11THE BATTLE FOR HEARTS AND MINDS

“America’s basic purposes have always been to

keep the peace, to foster progress, and to enhance liberty and dignity among nations. Progress toward these noble goals is persistently threatened by by the Cold War conflict now engulfing the world. We face a hostile ideology - global in scope, atheistic in character, ruthless in purpose, and insidious in method. We need to carry forward, steadily and surely, the burdens of a long and complex struggle.”

Eisenhower’s farewell address to the nation at the end of his presidency, January 1961

“It is clear that in the colonial countries the peasants alone are revolutionary for they have nothing to lose and everything to gain.”

Franz Fanon, A Dying Colonialism, 1959 p.61

”The deeper I enter into the culture and political circles the clearer I see that the great danger that threatens Africa is the absence of ideology.”

Franz Fanon, Toward the African Revolution 1964 p.186

Слайд 12The Cold War was not only a struggle between rival alliances with

competing military and strategic interests; it was also a struggle to win hearts and minds. Especially outside Cold War Europe, there was a battle of ideologies, attempting to attract and persuade ‘Third World’ countries through the strength of ideas, promises of prosperity and economic modernisation, and social and cultural values. The Cold War became a propaganda war; and this was fought not only by governments and diplomats. Academics and intellectuals put forward critical analysis of the Western and Soviet systems; politicians were influenced by shifts in public opinion, not least by dissent and demonstrations.

Слайд 13One aspect of Cold War competition between the United States and the

Soviet Union involved sparring over a range of environmental issues. Soviet political leaders claimed to manage resources in the name of the proletariat, whereas American officials spoke about the inviolability of private property. American specialists referred to great success in creating the legal framework to combat pollution; Soviet policy makers and scientists followed with the passage of statutes to demonstrate that the nation cared more about the citizen and the environment than the U.S. government did. Most observers agree that the United States won this Cold War battle owing to the successful implementation of the National Environmental Protection Act (1969), together with a series of clean air acts dating to 1955; the Clean Water Act (1972); and a variety of other legislative, juridical, and voluntary measures. Soviet policies and practices led to environmental degradation on a scale that may be exceeded only by current practices in China. The impacts on the environment and public health will continue to be felt for decades to come.

Слайд 14The Soviet environmental legacy is fields of toxic waste that continue to

leak into the groundwater and costly, massive, failed white elephants – nature transformation projects and huge inefficient factories – that dominate the landscape. In some regions, pollution led to the formation of extensive tracts of land devoid of trees, where only the hardiest of grasses survive, what might be called industrial deserts.

Слайд 15The first phase of the Cold War began shortly after the end

of the Second World War in 1945. The United States and its allies created the NATO military alliance in 1949 in the apprehension of a Soviet attack and termed their global policy against Soviet influence containment. The Soviet Union formed the Warsaw Pact in 1955 in response to NATO. Major crises of this phase included the 1948–49 Berlin Blockade, the 1927–1949 Chinese Civil War, the 1950–1953 Korean War, the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the 1956 Suez Crisis, the Berlin Crisis of 1961 and the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis. The US and the USSR competed for influence in Latin America, the Middle East, and the decolonizing states of Africa, Asia, and Oceania.

Слайд 16Following the Cuban Missile Crisis, a new phase began that saw the

Sino-Soviet split between China and the Soviet Union complicate relations within the Communist sphere, while France, a Western Bloc state, began to demand greater autonomy of action. The USSR invaded Czechoslovakia to suppress the 1968 Prague Spring, while the US experienced internal turmoil from the civil rights movement and opposition to the Vietnam War. In the 1960s–70s, an international peace movement took root among citizens around the world. Movements against nuclear weapons testing and for nuclear disarmament took place, with large anti-war protests. By the 1970s, both sides had started making allowances for peace and security, ushering in a period of détente that saw the Strategic Arms Limitation Talks and the US opening relations with the People's Republic of China as a strategic counterweight to the USSR. A number of self-proclaimed Marxist regimes were formed in the second half of the 1970s in the Third World, including Angola, Mozambique, Ethiopia, Cambodia, Afghanistan and Nicaragua.

Слайд 17Détente collapsed at the end of the decade with the beginning of

the Soviet–Afghan War in 1979. The early 1980s was another period of elevated tension. The United States increased diplomatic, military, and economic pressures on the Soviet Union, at a time when it was already suffering from economic stagnation. In the mid-1980s, the new Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev introduced the liberalizing reforms of glasnost ("openness", c. 1985) and perestroika ("reorganization", 1987) and ended Soviet involvement in Afghanistan in 1989. Pressures for national sovereignty grew stronger in Eastern Europe, and Gorbachev refused to militarily support their governments any longer.

Разработка новых моделей партнерств для МТС

Разработка новых моделей партнерств для МТС Хочу Пури

Хочу Пури Портрет выпускника начальной школы

Портрет выпускника начальной школы Презентация на тему День дошкольного работника

Презентация на тему День дошкольного работника План Вступ Одяг - це спосіб життя Бог моди Мода-як спосіб вираження особистості Джон Гальяно-останній романтик Екстравагантність к

План Вступ Одяг - це спосіб життя Бог моди Мода-як спосіб вираження особистості Джон Гальяно-останній романтик Екстравагантність к Урок информатики с элементами Православной Отечественной культуры

Урок информатики с элементами Православной Отечественной культуры Основные статистические понятия

Основные статистические понятия U

U Декоративно-прикладное искусство Руси

Декоративно-прикладное искусство Руси ОТКРЫТИЕ РОДИНЫ

ОТКРЫТИЕ РОДИНЫ сс

сс День статистики 2020

День статистики 2020 -входит в 30 крупнейших российских банков - имеет 15-летний стаж успешной работы на рынке банковских услуг - успешно пережил уже неско

-входит в 30 крупнейших российских банков - имеет 15-летний стаж успешной работы на рынке банковских услуг - успешно пережил уже неско Архивно-логистический центр Сбербанка России

Архивно-логистический центр Сбербанка России Аварии на радиационно-опасных объектах.Ионизирующее излучение.

Аварии на радиационно-опасных объектах.Ионизирующее излучение. 9 советов по составлению успешного объявления

9 советов по составлению успешного объявления N(이)나. Или/Что ли/хотя бы/может

N(이)나. Или/Что ли/хотя бы/может Подводный дом. Создание полигона подводно-технических обитаемых и робототезированных систем для обучения студентов

Подводный дом. Создание полигона подводно-технических обитаемых и робототезированных систем для обучения студентов Zipper fracture. Интерференция скважин

Zipper fracture. Интерференция скважин Опасности радиационных аварий

Опасности радиационных аварий  Презентация на тему: Персидская держава в VI веке до нашей эры

Презентация на тему: Персидская держава в VI веке до нашей эры Финансовая академия при Правительстве Российской Федерации

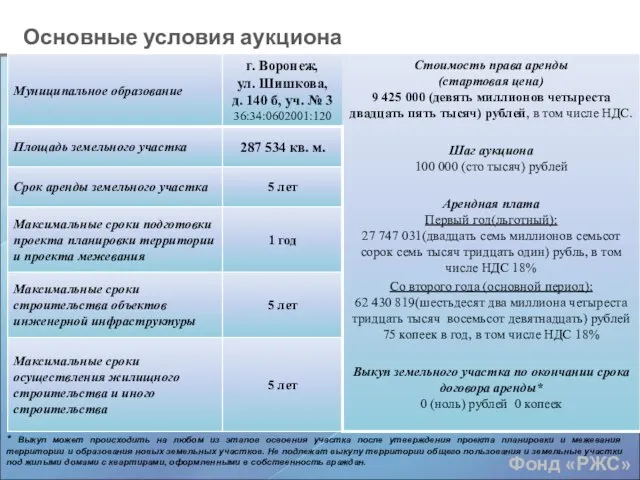

Финансовая академия при Правительстве Российской Федерации Основные условия аукциона

Основные условия аукциона Мониторинг злоупотребления наркотикамиОсновные ошибки составления годовых отчетов по нароклогии

Мониторинг злоупотребления наркотикамиОсновные ошибки составления годовых отчетов по нароклогии Выступление воспитателя 1 младшей группы МДОУ «Детский сад комбинированного вида № 218» Заводского района г. Саратова Селиверстов

Выступление воспитателя 1 младшей группы МДОУ «Детский сад комбинированного вида № 218» Заводского района г. Саратова Селиверстов Формы деятельности классного руководителя по духовно-нравственному направлению воспитательной работы

Формы деятельности классного руководителя по духовно-нравственному направлению воспитательной работы Криптогрфия и шифры. Азы шифрования

Криптогрфия и шифры. Азы шифрования