Слайд 2Biber, Douglas, Stig Johansson, Geoffrey Leech, Susan Conrad and Edward Finegan (1999),

Longman Grammar of Spoken and Written English, London: Longman.

Quirk, Randolph and Sidney Greenbaum (1973), A University Grammar of English, London: Longman.

Quirk, Randolph, Sidney Greenbaum, Geoffrey Leech and Jan Svartvik (1985), A Comprehensive Grammar of the English Language, London: Longman.

The above three books are not textbooks for reading but grammars to be dipped into. They are for the reader interested in investigating particular points of English grammar.

Слайд 3Syntax has to do with how words are put together to build

phrases, with how phrases are put together to build clauses or bigger phrases, and with how clauses are put together to build sentences.

Слайд 4In small and familiar situations, humans could communicate using single words and

many gestures, particularly when dealing with other members of the same social grouping (family and so on). But complex messages for complex situations or complex ideas require more than just single words; every human language has devices with which its speakers can construct phrases and clauses.

Слайд 5

PHRASE: Heads and modifiers

Two central ideas:

The first, is that certain relationships hold

between words whereby one word, the head, controls the other words, the modifiers. A given head may have more than one modifier, and may have no modifier.

Слайд 6The second idea is that words are grouped into phrases and that

groupings typically bring together heads and their modifiers. In the large dog, the word dog is the head, and the and large are its modifiers. In barked loudly, the word barked is the head and loudly the modifier.

Слайд 7A phrase, then, is a group of interrelated words.

In such groups we

recognise various links among the words, between heads and their modifiers. This relationship of modification is fundamental in syntax.

Слайд 8How are we to understand the statement ‘one word, the head, controls

the other words, the modifiers’? Consider the sentences in (1)–(2), which also introduce the use of the asterisk – ‘*’ – to mark unacceptable examples.

(1) a. Jane was sitting at her desk.

b. *The Jane was sitting at her desk.

(2) a. *Accountant was sitting at her desk.

b. The accountant was sitting at her desk.

c. Accountants audit our finances every year.

Слайд 9Example (1a Jane was sitting at her desk.) is a grammatical sentence

of English, but (1b The Jane was sitting at her desk.) is not grammatical (at least as an example of standard English). Jane is a type of noun that typically excludes words such as the and a.

Слайд 10Accountant is a different type of noun; if it is singular, as

in (2a*Accountant was sitting at her desk.), it requires a word such as the or a. In (2c Accountants audit our finances every year.), accountants consists of accountant plus the inflection -s and denotes more than one accountant. It does not require the.

Слайд 11Another type of noun, which includes words such as salt, sand and

water, can occur without any word such as the, a or some, as in (3a), and can occur in the plural but only with a large change in meaning. Example (3b) can only mean that different types of salt were spread.

(3) a. The gritter spread salt.

b. The gritter spread salts.

gritter NOUN British A vehicle or machine for spreading grit and often salt on roads in icy or potentially icy weather.

Слайд 12Note too that a plural noun such as gritters allows either less

or fewer, as in (4d) and (4c), whereas salt requires less and excludes fewer, as in (4a) and (4b).

(5) a. This gritter spread less salt than that one.

b. *This gritter spread fewer salt than that one.

c. There are fewer gritters on the motorway this winter.

d. There are less gritters on the motorway this winter.

Слайд 13The central property of the above examples is that Jane, accountant, salt

and gritter permit or exclude words such as the, a, some, less and fewer – note that Jane excludes the, a, some, less and fewer; salt in excludes a and fewer; gritters excludes a; accountant allows both the and a, and so on.

Слайд 14We have looked at phrases with nouns as the controlling word, but

other types of word exercise similar control. Many adjectives such as sad or big allow words such as very to modify them – very sad, very big – but exclude words such as more – sadder is fine but more sad is at the very least unusual. Other adjectives, such as wooden, exclude very and more – *very wooden, *more wooden. That is, wooden excludes very and more in its literal meaning, but note that very is acceptable when wooden has a metaphorical meaning, as in The policeman had a very wooden expression.

Слайд 15Even a preposition can be the controlling word in a group. Prepositions

link nouns to nouns (books about antiques), adjectives to nouns (rich in minerals) and verbs to nouns (aimed at the target). Most prepositions must be followed by a group of words containing a noun, or by a noun on its own, as in (They sat) round the table, (Claude painted) with this paint-brush, (I’ve bought a present) for the children. A small number of prepositions allow another preposition between them and the noun: In behind the woodpile (was a hedgehog.)

Слайд 16

Heads, modifiers and meaning

The distinction between heads and modifiers has been put

in terms of one word, the head, that controls the other words in a phrase, the modifiers. If we think of language as a way of conveying information – which is what every speaker does with language some of the time – we can consider the head as conveying a central piece of information and the modifiers as conveying extra information.

Слайд 17Thus in the phrase expensive books the head word books indicates the

very large set of things that count as books, while expensive indicates that the speaker is drawing attention not to the whole set but to the subset of books that are expensive. In the longer phrase the expensive books, the word the signals that the speaker is referring to a set of books which have already been mentioned or are otherwise obvious in a particular context.

Слайд 18The same narrowing-down of meaning applies to phrases containing verbs. Different verbs

have different powers of control. Some verbs, as in (6a), exclude a direct object, other verbs require a direct object, as in (6b), and a third set of verbs allows a direct object but does not require one, as in (6c).

(6) a. *The White Rabbit vanished his watch / The White Rabbit vanished.

b. Dogs chase cats / *Dogs chase.

c. Flora cooks / Flora cooks gourmet meals.

Слайд 19Consider the examples drove and drove a Volvo. Drove indicates driving in

general; drove a Volvo narrows down the activity to driving a particular make of car.

Слайд 20Heads may have several modifiers. This is most easily illustrated with verbs;

the phrase bought a present for Jeanie in Jenners last Tuesday contains four modifiers of bought – a present, for Jeanie, in Jenners and last Tuesday. A present signals what was bought and narrows down the activity from just buying to buying a present as opposed, say, to buying the weekly groceries. For Jeanie narrows the meaning down further – not just ‘buy a present’ but ‘buy a present for Jeanie’, and similarly for the phrases in Jenners and last Tuesday.

Слайд 21Complements and adjuncts

Modifiers fall into two classes – obligatory modifiers, known as

complements, and optional modifiers, known as adjuncts.

Слайд 22The distinction was first developed for the phrases that modify verbs, and

indeed applies most easily to the modifiers of verbs, but the distinction is also applied to the modifiers of nouns.

Слайд 23The verb can be seen as controlling every other phrase in the

clause. Consider:

My mother bought a present for Jeanie in Jenners last Tuesday.

(My) mother is the subject of the verb. The subject of a clause plays an important role; nonetheless, in a given clause the verb controls the subject noun too. Bought requires a human subject noun; that is, it does in everyday language but behaves differently in the language of fairy stories, which narrate events that are unconstrained by the biological and physical laws of this world.

Слайд 24A verb such as flow requires a subject noun denoting a liquid;

if in a given clause it has a subject noun denoting some other kind of entity, flow imposes an interpretation of that entity as a liquid. Thus people talk of a crowd flowing along a road, of traffic flowing smoothly or of ideas flowing freely.

Слайд 25Returning to the clause My mother bought a present for Jeanie in

Jenners last Tuesday, we will say that the verb bought controls all the other phrases in the clause and is the head of the clause. It requires a human noun to its left, here mother; it requires a noun to its right that denotes something concrete (although we talk figuratively of buying ideas in the sense of agreeing with them). It allows, but does not require, time expressions such as last Tuesday and place expressions such as in Jenners.

Слайд 26Such expressions convey information about the time when some event happened and

about the place where it happened. With verbs, such time and place expressions are always optional and are held to be adjuncts.

Слайд 27Phrases that are obligatory are called complements. (The term ‘complement’ derives from

a Latin verb ‘to fill’; the idea conveyed by ‘complement’ is that a complement expression fills out the verb (or noun and so on), filling it out or completing it with respect to syntax but also with respect to meaning.

Слайд 28The term ‘adjunct’ derives from the Latin verb ‘join’ or ‘add’ and

simply means ‘something adjoined’, tacked on and not part of the essential structure of clauses.)

Слайд 29The relationships between heads and modifiers are called dependencies or dependency relations.

Heads have been described as controlling modifiers; modifiers are said to depend on, or to be dependent on, their heads. Heads and their modifiers typically cluster together to form a phrase.

Слайд 30In accordance with a long tradition in Europe, verbs are treated as

the head, not just of phrases, but of whole clauses (Miller Jim An Introduction to English Syntax Edinburgh University Press 2002).

Слайд 31In clauses, the verb and its complements tend to occur close together,

with the adjuncts pushed towards the outside of the clause, as shown by the examples in (9).

(9) a. Maisie drove her car from Morningside to Leith on Wednesday.

b. On Wednesday Maisie drove her car from Morningside to Leith.

c. Maisie drove her car on Wednesday from Morningside to Leith.

МОУ гимназия № 1

МОУ гимназия № 1 Промышленное производство аммиака

Промышленное производство аммиака Серебряный век в искусстве

Серебряный век в искусстве Алгоритм отработки лидов

Алгоритм отработки лидов Презентация на тему Атмосферные осадки

Презентация на тему Атмосферные осадки  Сочетание устойчивого развития и сохранения исторической памяти

Сочетание устойчивого развития и сохранения исторической памяти Социальная коммуникация. Лекция 1

Социальная коммуникация. Лекция 1 Анкета клиента на проведение аудита

Анкета клиента на проведение аудита Псковская судная грамота: общая характеристика

Псковская судная грамота: общая характеристика Первичная обработка кролика

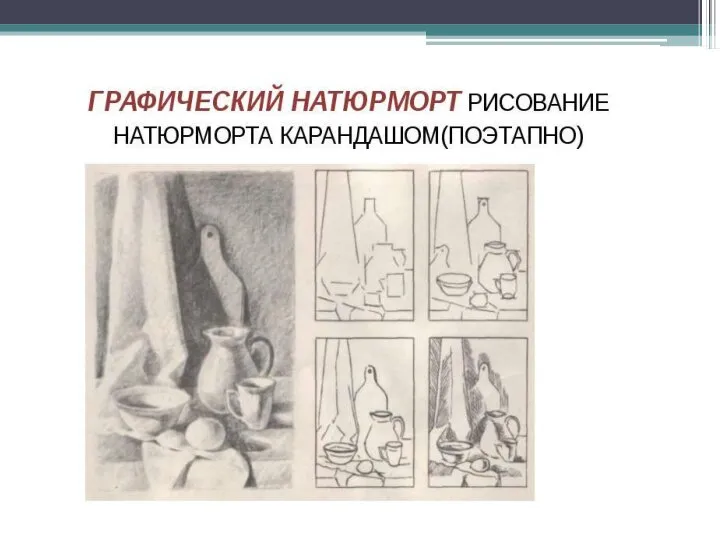

Первичная обработка кролика Конструктивное построение предметов

Конструктивное построение предметов Презентация на тему Основная позиция пальцев на клавиатуре

Презентация на тему Основная позиция пальцев на клавиатуре  Политическая социализация

Политическая социализация ОСНОВНЫЕ ПАРАМЕТРЫ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯ R-TGI (РОССИЙСКИЙ ИНДЕКС ЦЕЛЕВЫХ ГРУПП) Ежеквартальное измерение особенностей потребления товаров,

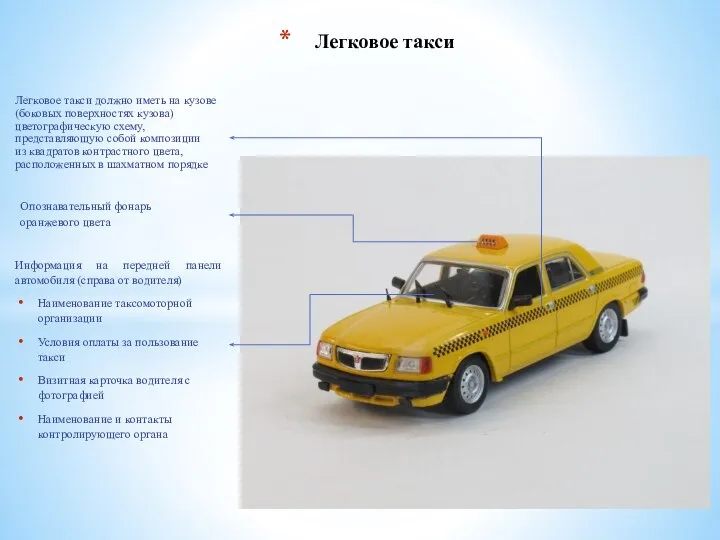

ОСНОВНЫЕ ПАРАМЕТРЫ ИССЛЕДОВАНИЯ R-TGI (РОССИЙСКИЙ ИНДЕКС ЦЕЛЕВЫХ ГРУПП) Ежеквартальное измерение особенностей потребления товаров, Легковое такси

Легковое такси ЕГЭ по литературе: сдаю или сдаюсь?

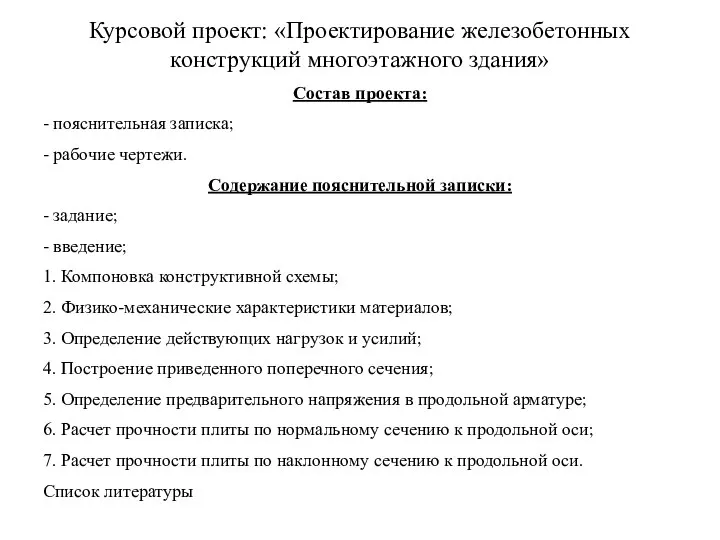

ЕГЭ по литературе: сдаю или сдаюсь? Курсовой проект: Проектирование железобетонных конструкций многоэтажного здания

Курсовой проект: Проектирование железобетонных конструкций многоэтажного здания «Значение имени Маргарита

«Значение имени Маргарита Значение страхования жизни и пенсионного обеспечения для украинского общества

Значение страхования жизни и пенсионного обеспечения для украинского общества Интервальное голодание. Меню

Интервальное голодание. Меню Здоровый ребёнок-Здоровое будущее!!!

Здоровый ребёнок-Здоровое будущее!!! Административно-правовые основы управления. Часть II

Административно-правовые основы управления. Часть II Такие знакомые и неизвестные нам пчелы

Такие знакомые и неизвестные нам пчелы Эй, народ честной, одевай кафтаны цветастые, платья красные и айда гулять на ярмарку – на народ посмотреть, да себя показать!!! А на я

Эй, народ честной, одевай кафтаны цветастые, платья красные и айда гулять на ярмарку – на народ посмотреть, да себя показать!!! А на я Коми кывйысь урок .Чачаяс вузасянiнын. Урок коми языка. В магазине игрушек

Коми кывйысь урок .Чачаяс вузасянiнын. Урок коми языка. В магазине игрушек ДОЖДЬ

ДОЖДЬ Гранулоцитарный колониестимулирующий фактор (G-CSF, Г-КСФ): молекулярная биология, биотехнология, производство лекарственных форм, к

Гранулоцитарный колониестимулирующий фактор (G-CSF, Г-КСФ): молекулярная биология, биотехнология, производство лекарственных форм, к Презентация на тему Круговорот веществ и превращение энергии в экосистеме

Презентация на тему Круговорот веществ и превращение энергии в экосистеме