- Главная

- Педагогика

- Interview. Week 12

Содержание

- 2. Interview Usually, interviewing is defined simply as a conversation with a purpose. Specifically, the purpose is

- 3. Types of Interviews. No consideration of interviewing would be complete without at least some acknowledgment of

- 4. How to begin the process? The first step to interview construction has already been implied: Specifically,

- 5. The organization of questions. The specific ordering (sequencing), phrasing, level of language, adherence to subject matter,

- 6. Types of Questions. Essential Questions. Essential questions exclusively concern the central focus of the study. They

- 7. Effective communication. Perhaps the most serious problem with asking questions is how to be certain the

- 8. Problems Affectively Worded Questions. Affective words arouse in most people some emotional response, usually negative. Although

- 9. Long and Short Interviews. Interviewing can be a very time-consuming, albeit valuable, data-gathering technique. It is

- 10. Developing Rapport. One dominant theme in the literature on interviewing centers on the interviewer’s ability to

- 11. The Ten Commandments of Interviewing 1. Never begin an interview cold. 2. Remember your purpose. 3.

- 13. Скачать презентацию

Слайд 2Interview

Usually, interviewing is defined simply as a conversation with a purpose. Specifically,

Interview

Usually, interviewing is defined simply as a conversation with a purpose. Specifically,

Unfortunately, the consensus on how to conduct an interview is not nearly as high. Interviewing and training manuals vary from long lists of specific do's and don'ts to lengthy, abstract, pseudo theoretical discussions on empathy, intuition, and motivation.

Research, particularly field research, is sometimes divided into two separate phases—namely, getting in and analysis (Shaffir et al., 1980). Getting in is typically defined as various techniques and procedures intended to secure access to a setting, its participants, and knowledge about phenomena and activities being observed. Analysis makes sense of the information accessed during the getting-in phase.

Слайд 3Types of Interviews.

No consideration of interviewing would be complete without at

Types of Interviews.

No consideration of interviewing would be complete without at

At least three major categories may be identified (Babbie, 1995; Denzin, 1978; Frankfort-Nachmias & Nachmias, 1996; Gorden, 1987; Nieswiadomy 1993): the standardized (formal or structured) interview, the unstandardized (informal or non-directive) interview, and the semistandardized (guided-semistructured or focused) interview.

Слайд 4How to begin the process?

The first step to interview construction has

How to begin the process?

The first step to interview construction has

Selltiz et al. (1959), Spradley (1979), Patton (1980), and Polit and Hungler (1993) suggest that researchers begin with a kind of outline, listing all the broad categories they feel may be relevant to their study.

Following this, separate lists of questions for each of the major thematic categories were developed.

Слайд 5The organization of questions.

The specific ordering (sequencing), phrasing, level of language,

The organization of questions.

The specific ordering (sequencing), phrasing, level of language,

In order to draw out the most complete story about various subjects or situations under investigation, four types or styles of questions must be included in the survey instrument: essential questions, extra questions, throw-away questions, and probing questions.

Слайд 6Types of Questions.

Essential Questions. Essential questions exclusively concern the central focus

Types of Questions.

Essential Questions. Essential questions exclusively concern the central focus

Extra Questions. Extra questions are those questions roughly equivalent to certain essential ones but worded slightly differently. These are included in order to check on the reliability of responses (through examination of consistency in response sets) or to measure the possible influence a change of wording might have.

Throw-Away Questions. Frequently, you find throw-away questions toward the beginning of an interview schedule. Throw-away questions may be essential demographic questions or general questions used to develop rapport between interviewers and subjects.

Probing questions, or simply probes, provide interviewers with a way to draw out more complete stories from subjects.

Слайд 7Effective communication.

Perhaps the most serious problem with asking questions is how

Effective communication.

Perhaps the most serious problem with asking questions is how

Researchers must always be sure they have clearly communicated to the subjects what they want to know. The interviewers' language must be understandable to the subject; ideally, interviews must be conducted at the level or language of the respondents.

Слайд 8Problems

Affectively Worded Questions. Affective words arouse in most people some emotional

Problems

Affectively Worded Questions. Affective words arouse in most people some emotional

The Double-Barreled Question. Among the more common problems that arise in constructing survey items is the double-barreled question. This type of question asks a subject to respond simultaneously to two issues in a single question. For instance, one might ask, "How many times have you smoked marijuana, or have you only tried cocaine?“

Complex Questions. The pattern of exchange that constitutes verbal communication in Western society involves more than listening. When one person is speaking, the other is listening, anticipating, and planning how to respond. Consequently, when researchers ask a long, involved question, the subjects may not really hear the question in its entirety.

Слайд 9Long and Short Interviews.

Interviewing can be a very time-consuming, albeit valuable, data-gathering

Long and Short Interviews.

Interviewing can be a very time-consuming, albeit valuable, data-gathering

If potential answers to research questions can be obtained by asking only a few questions, then the interview may be quite brief. If, on the other hand, the research question(s) are involved, or multi-layered, it may require a hundred or more questions. Length also depends upon the type of answers constructed between the interviewer and the subject. In some cases, where the conversation is flowing, a subject may provide rich, detailed, and lengthy answers to the question.

Слайд 10Developing Rapport.

One dominant theme in the literature on interviewing centers on

Developing Rapport.

One dominant theme in the literature on interviewing centers on

There is little question that, as Stone (1962, p. 88) states, "Basic to the communication of the interview meaning is the problem of appearance and mood Clothes.

Слайд 11The Ten Commandments of Interviewing

1. Never begin an interview cold.

2. Remember your

The Ten Commandments of Interviewing

1. Never begin an interview cold.

2. Remember your

3. Present a natural front.

4. Demonstrate aware hearing.

5. Think about appearance.

6. Interview in a comfortable place.

7. Don't be satisfied with monosyllabic answers.

8. Be respectful.

9. Practice, practice, and practice some more.

10. Be cordial and appreciative.

Правила поведения в школе

Правила поведения в школе Көндәлек режим- Режим дня

Көндәлек режим- Режим дня Мың бір мақал, жүз бір жұмбақ. Сайыс сабақ

Мың бір мақал, жүз бір жұмбақ. Сайыс сабақ Жизнь без барьеров

Жизнь без барьеров Технология развития логики и памяти

Технология развития логики и памяти Педагогическая мастерская. Влияние уровневой дифференциации на качество знаний и развитие каждого ребенка

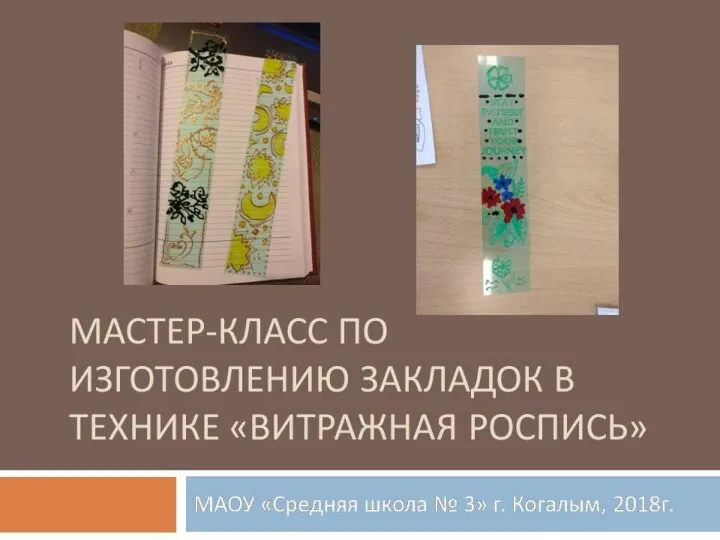

Педагогическая мастерская. Влияние уровневой дифференциации на качество знаний и развитие каждого ребенка Витражная роспись. Изготовление закладок

Витражная роспись. Изготовление закладок Букварь Жукова

Букварь Жукова Методика подготовки и проведения городского конкурса обучающихся Лучший стендовый доклад

Методика подготовки и проведения городского конкурса обучающихся Лучший стендовый доклад Школа умных игр ИгрУмка. Викторина

Школа умных игр ИгрУмка. Викторина Нади 10 отличий

Нади 10 отличий Краеведение. Дары леса

Краеведение. Дары леса Основные направления и подходы к обучению иностранным языкам. Часть 3

Основные направления и подходы к обучению иностранным языкам. Часть 3 Биоэнергопластика в коррекционной работе учителя-логопеда

Биоэнергопластика в коррекционной работе учителя-логопеда Двигательно-игровая деятельность с детьми вне занятий

Двигательно-игровая деятельность с детьми вне занятий Аппликация из кругов

Аппликация из кругов Пластилин и стаканчики. 4 класс

Пластилин и стаканчики. 4 класс Критерии оценки достоверности результатов эмпирического исследования

Критерии оценки достоверности результатов эмпирического исследования Мои питомцы

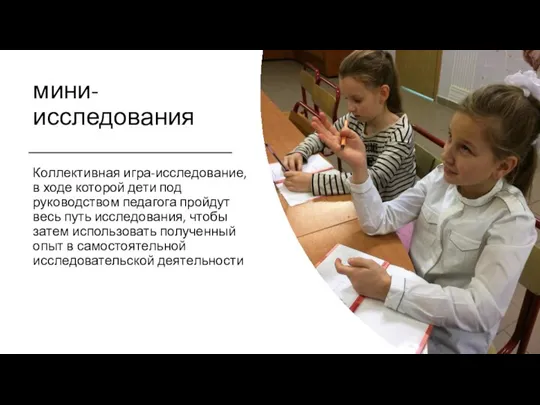

Мои питомцы Мини-исследования. Занятие 2

Мини-исследования. Занятие 2 Игра по теме Комнатные растения

Игра по теме Комнатные растения Кукла на проволочном каркасе

Кукла на проволочном каркасе Веселый эрудит. Викторина

Веселый эрудит. Викторина Детское экспериментирование как средство развития познавательной активности детей старшего дошкольного возраста

Детское экспериментирование как средство развития познавательной активности детей старшего дошкольного возраста Сбор и запись данных. Единицы измерения в Международной системе единиц

Сбор и запись данных. Единицы измерения в Международной системе единиц Драматургия игры. Структура игры

Драматургия игры. Структура игры Принципы методической работы воспитателя

Принципы методической работы воспитателя Своя игра. Поэтическая тетрадь

Своя игра. Поэтическая тетрадь