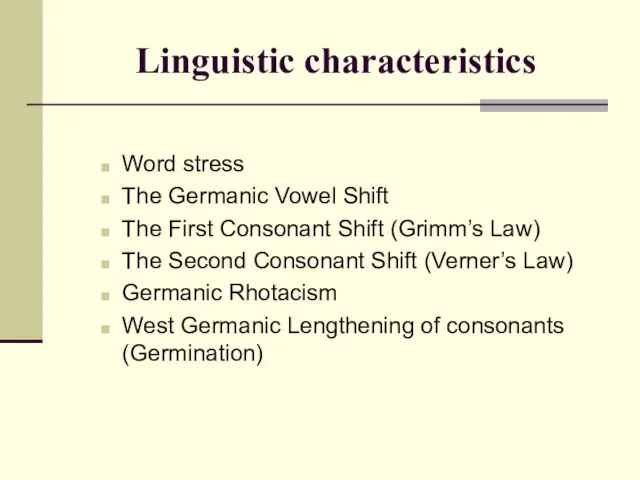

Слайд 2Linguistic characteristics

Word stress

The Germanic Vowel Shift

The First Consonant Shift (Grimm’s Law)

The Second

Consonant Shift (Verner’s Law)

Germanic Rhotacism

West Germanic Lengthening of consonants (Germination)

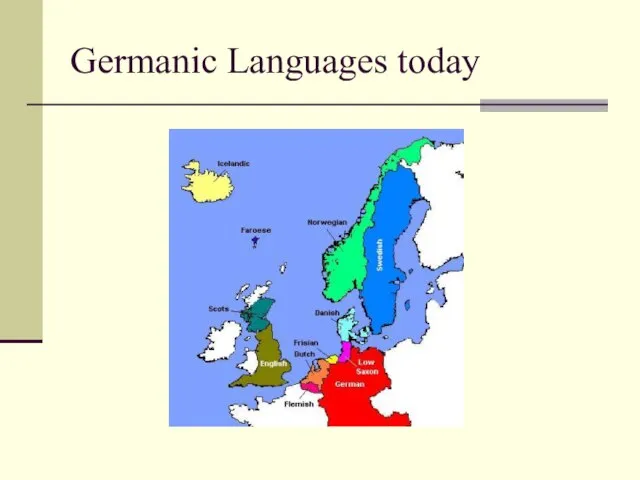

Слайд 3 Germanic languages in the modern world are:

English (Great Britain, the USA,

Canada, Australia, New Zealand and other countries);

Danish (Denmark);

German (Germany, Austria, Luxemburg, Switzerland);

Afrikaans (South African Republic);

Swedish (Sweden);

Icelandic (Iceland).

Слайд 5the parent-language

the Proto-Germanic language

split from related IE languages between the 15th

and 10th c. B.C

was never recorded in a written form

in the 19th century it was reconstructed by methods of comparative linguistics from written evidence in descendant languages

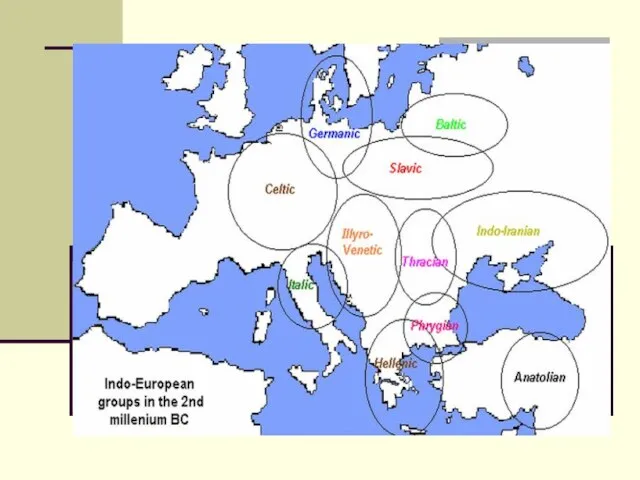

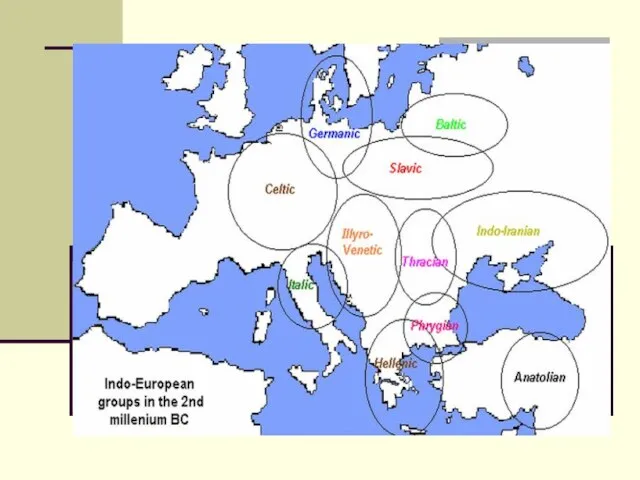

Слайд 6The Indo-European background

Слайд 7The Old Germanic languages form 3 groups

East Germanic

North Germanic

West Germanic

Слайд 8East Germanic

was formed by the tribes who returned from Scandinavia at the

beginning of our era

the Goths were the most powerful

the Gothic language is presented in written records of the 6th c.

Ulfilas’ Gospels – a manuscript of about 200 pages, 5th -6th century

Слайд 9Ulfilas Gospels

a translation of the Gospels from Greek into Gothic by Ulfilas

Ulfilas, a West Gothic bishop

Слайд 10East Germanic languages

Vandalic, Burgundian

left no written traces

Слайд 11North Germanic

the North Germanic tribes lived on the southern coasts of

the Scandinavian peninsula and in Northern Denmark (since the 4th c.)

spoke Old Norse or Old Scandinavian

runic inscriptions dated the 3d - 9th c.

Runic inscriptions were carved on objects made of hard material

Слайд 12North Germanic

Old Danish

Old Norwegian

Old Swedish

Icelandic

Faroese

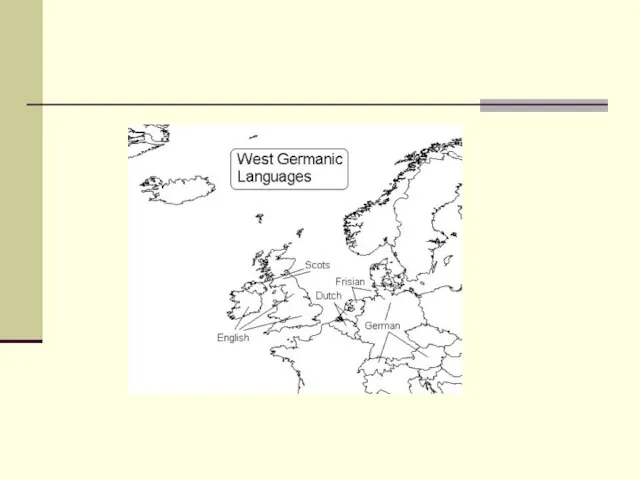

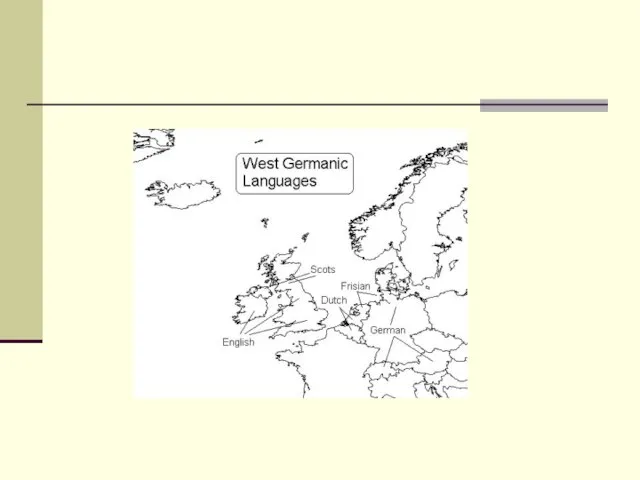

Слайд 13West Germanic

dwelt in the lowlands between the Oder and the Elbe

spoke Old High German (8th c.)

Old English (7th c.)

Old Saxon (9th c.)

Old Dutch (12th c.)

Слайд 15Word Stress

In ancient IE the stress was free and movable

it could fall

on any syllable of the word. It could be shifted (e.g. R. домом, дома, дома).

in late PG its position in the word was stabilized

was fixed on the first syllable

other syllables - suffixes and endings – were unstressed

Слайд 16Word stress

was no longer movable

unstressed syllables were phonetically weakened and

lost

weakening affected mostly suffixes and endings

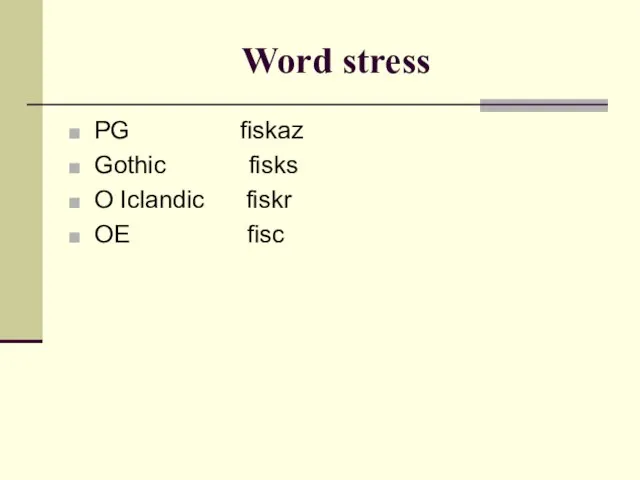

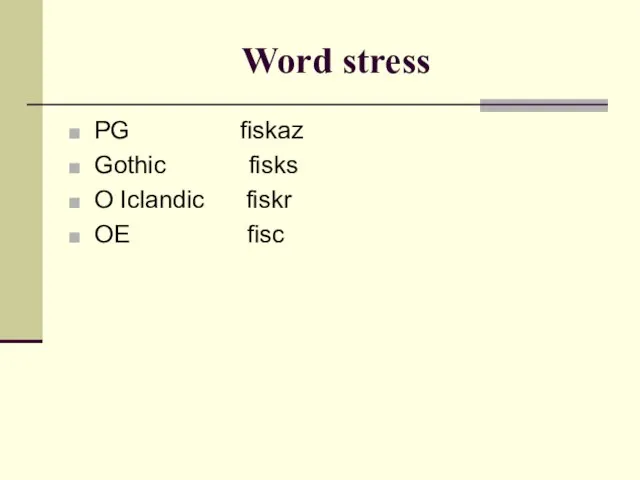

Слайд 17Word stress

PG fiskaz

Gothic fisks

O Iclandic fiskr

OE fisc

Слайд 18The Germanic Vowel Shift

vowels showed a strong tendency to change:

qualitative change

quantitative

change

dependent change

independent change

Слайд 19The Germanic Vowel Shift

IE short o and a > in Germanic more

open a

e.g. octo -- acht

IE long o and a were narrowed to long o

e.g. Lat.pous -- OE fot

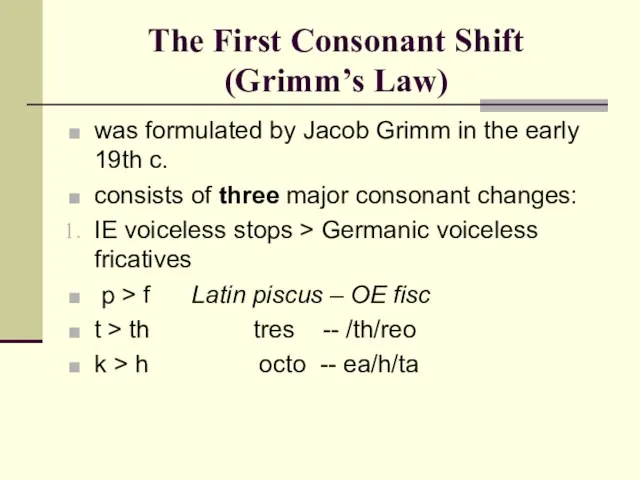

Слайд 20The First Consonant Shift

(Grimm’s Law)

was formulated by Jacob Grimm in

the early 19th c.

consists of three major consonant changes:

IE voiceless stops > Germanic voiceless fricatives

p > f Latin piscus – OE fisc

t > th tres -- /th/reo

k > h octo -- ea/h/ta

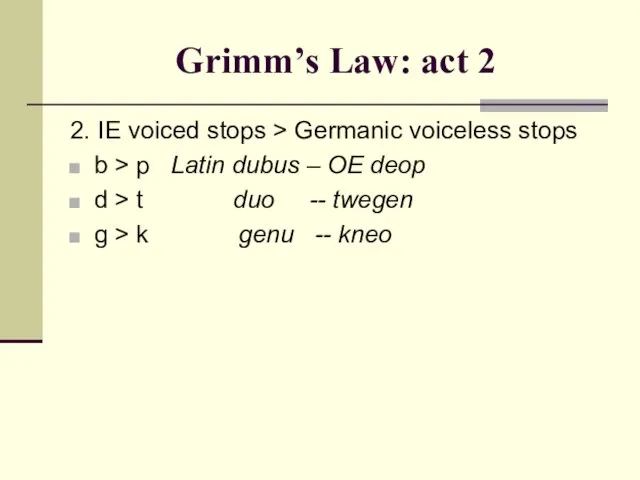

Слайд 21Grimm’s Law: act 2

2. IE voiced stops > Germanic voiceless stops

b >

p Latin dubus – OE deop

d > t duo -- twegen

g > k genu -- kneo

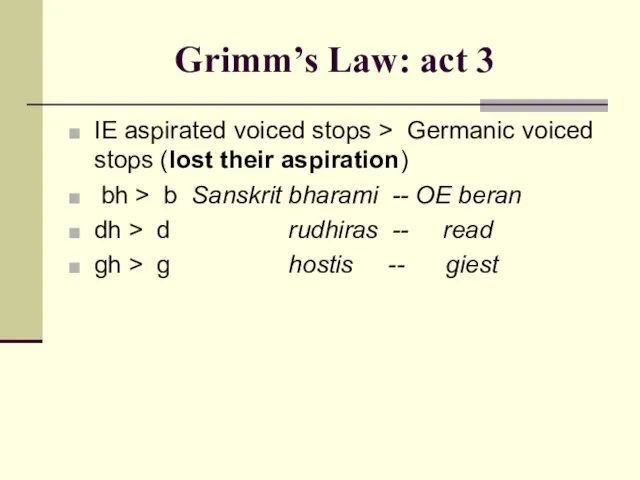

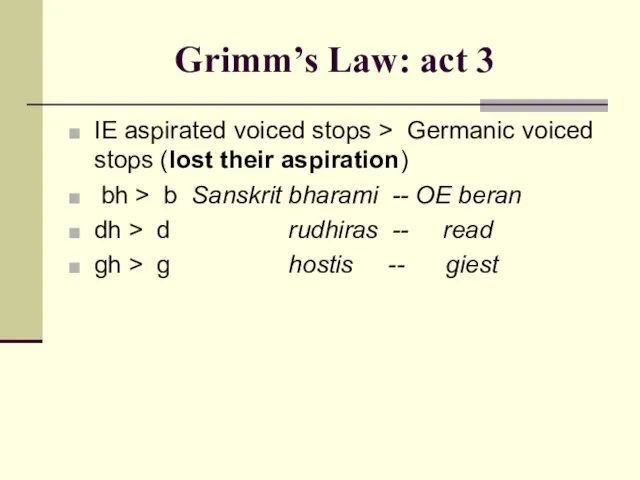

Слайд 22Grimm’s Law: act 3

IE aspirated voiced stops > Germanic voiced stops (lost

their aspiration)

bh > b Sanskrit bharami -- OE beran

dh > d rudhiras -- read

gh > g hostis -- giest

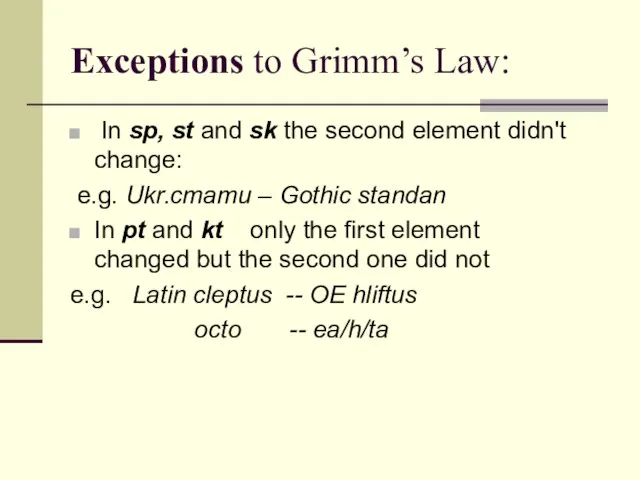

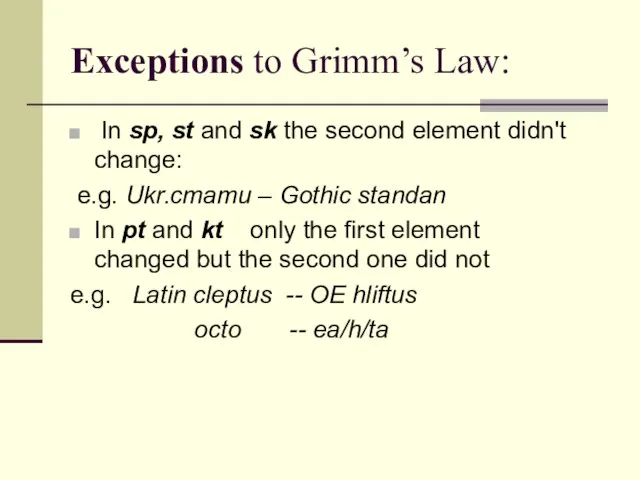

Слайд 23Exceptions to Grimm’s Law:

In sp, st and sk the second element

didn't change:

e.g. Ukr.стати – Gothic standan

In pt and kt only the first element changed but the second one did not

e.g. Latin cleptus -- OE hliftus

octo -- ea/h/ta

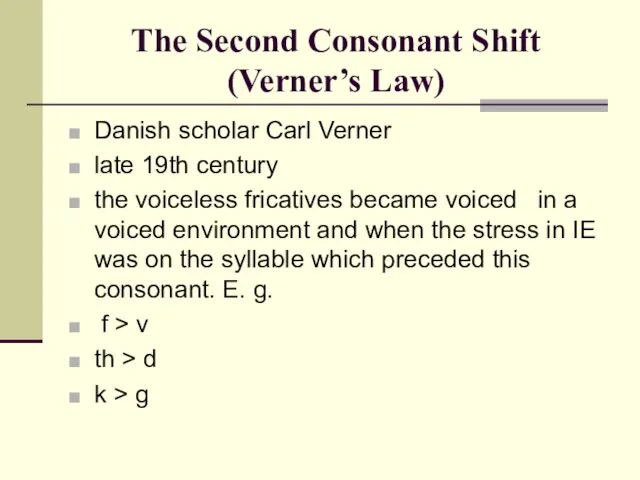

Слайд 24The Second Consonant Shift (Verner’s Law)

Danish scholar Carl Verner

late 19th

century

the voiceless fricatives became voiced in a voiced environment and when the stress in IE was on the syllable which preceded this consonant. E. g.

f > v

th > d

k > g

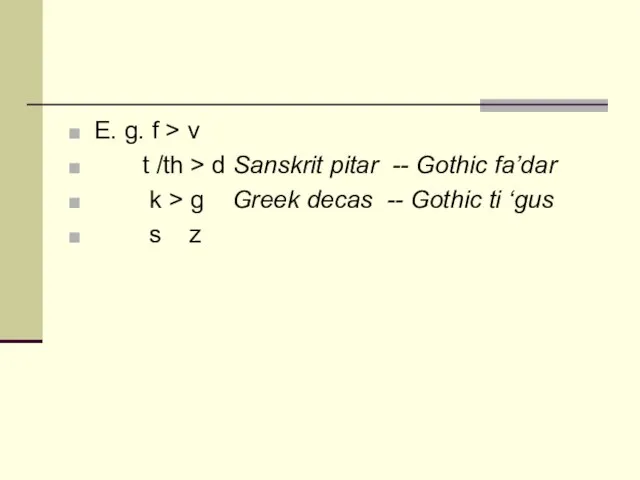

Слайд 25E. g. f > v

t /th > d Sanskrit pitar --

Gothic fa’dar

k > g Greek decas -- Gothic ti ‘gus

s z

Слайд 26Germanic Rhotacism

from Greek name of the letter r (rho)

z

--- r

The consonant /z/ that resulted from the voiceless fricative /s/ by Verner’s Law developed into /r/ in North and West Germanic Languages

Слайд 27/r/ in North Germanic, e.g. OIcl dagr

/s/ in East Germanic, e.g. Gothic

dags

/r/ or it could disappear at the end of the word in West Germanic e.g. OE daeg

Слайд 28West Germanic Lengthening of Consonants

Germination

Short /single consonants except r were lengthened

if preceded by a short vowel and followed by i or j

E.g. Gothic badi – OE bedd

Слайд 29Periods of the History of the English Language

Traditional periodisation

Henry Sweet’s division of

the History of the Language

Approach of Yuri Kostyuchenko

Слайд 30Traditional Periodisation

Old English (sometimes referred to as Anglo-Saxon, 449 – 1066)

Middle

English (1066 - 1475)

Modern English (1476 – up to now)

Слайд 31Important Dates

449 – Anglo-Saxon conquest of Britain

1066 – the Norman Conquest

1475

– Introduction of Printing

Слайд 32Henry Sweet’s division

OE is the period of full inflections (e.g. nama,

gifan, caru)

ME of leveled inflections (naame, given, caare)

Modern E of lost inflections (naam, giv, caar).

Слайд 33Approach of Yuri Kostyuchenko

Period to 449

Period after 449 is subdivided into:

Old

English V-XI centuries

Middle E XII-XV

period of formation of the standard language XV-XVII

New English – the second half of the 17th century up to now

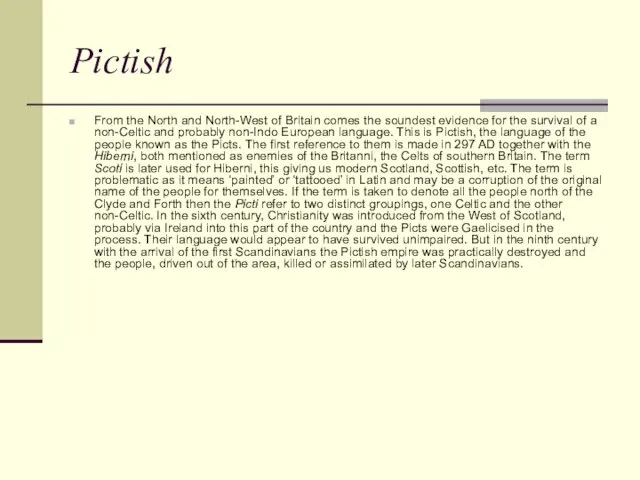

Слайд 36Pictish

From the North and North-West of Britain comes the soundest evidence for

the survival of a non-Celtic and probably non-Indo European language. This is Pictish, the language of the people known as the Picts. The first reference to them is made in 297 AD together with the Hiberni, both mentioned as enemies of the Britanni, the Celts of southern Britain. The term Scoti is later used for Hiberni, this giving us modern Scotland, Scottish, etc. The term is problematic as it means ‘painted’ or ‘tattooed’ in Latin and may be a corruption of the original name of the people for themselves. If the term is taken to denote all the people north of the Clyde and Forth then the Picti refer to two distinct groupings, one Celtic and the other non-Celtic. In the sixth century, Christianity was introduced from the West of Scotland, probably via Ireland into this part of the country and the Picts were Gaelicised in the process. Their language would appear to have survived unimpaired. But in the ninth century with the arrival of the first Scandinavians the Pictish empire was practically destroyed and the people, driven out of the area, killed or assimilated by later Scandinavians.

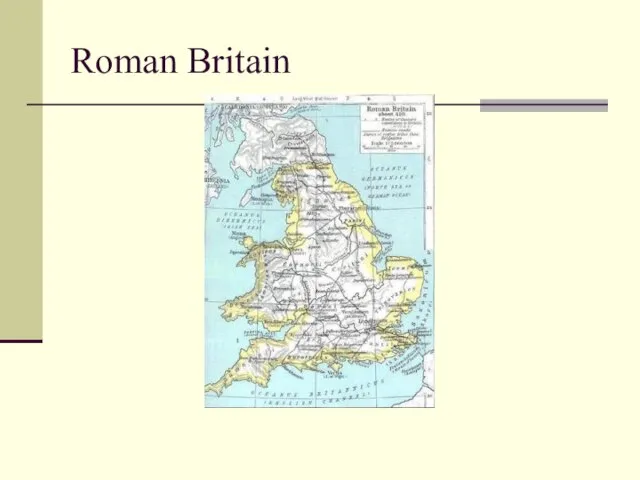

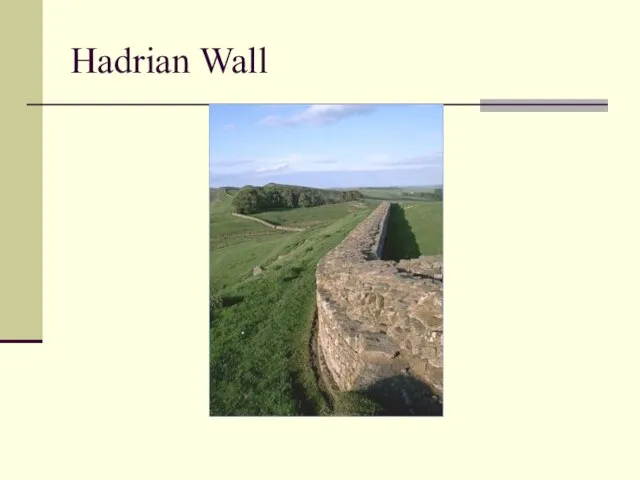

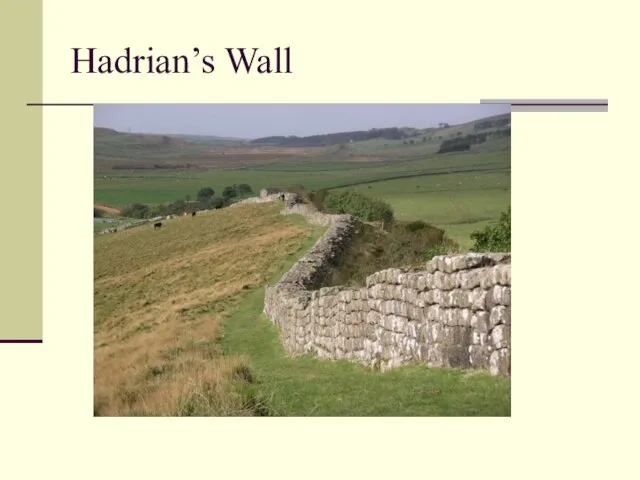

Слайд 38Written history in Britain starts with Julius Caesar who in 55 or

54 BC invaded the island and left an account of this for posterity. The Romans were never really interested in Britain and did not take the trouble to conquer it entirely. Thus in the West Cornwall and Wales remained firmly Celtic, as did the North and all of Scotland. It is true that Hadrian’s Wall (built c. 122-130) is quite far north (near the present-day border with Scotland but Roman settlements in the north of England are rare. The two main Roman groups are the Catuvellauni north of the Thames and the Atrebates south of this river. The Roman groupings in Britain tended to distance themselves from Rome and to some extent enter alliances with local (Celtic) leaders. The Celtic areas provided welcome refuge for Roman leaders who were in trouble with fellow Romans in Britain. Things came to a head in the early part of the first century AD and a Roman invasion of Britain in 43-47 AD under the emperor Claudius was supposed to put an end to this strife. Military engagements continued throughout the first century and into the second with an approximate status quo being achieved with the building of Hadrian’s Wall. Wales remained a stronghold of Celtic resistance to Roman rule and no attempt to subdue the Welsh was successful

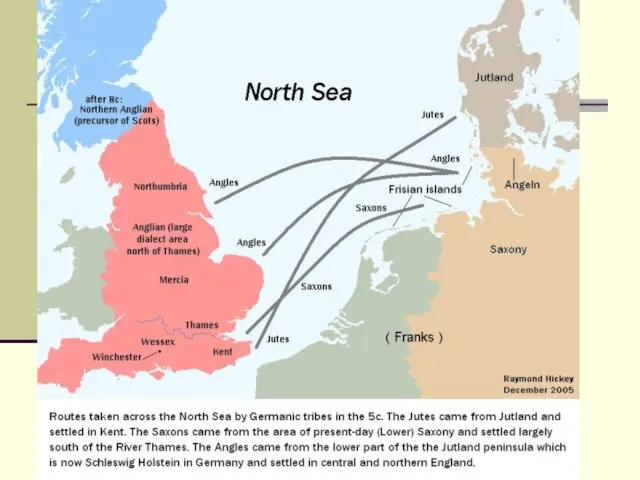

Слайд 44Germanic Invasion

The withdrawal of the Romans from England in the early 5th

century left a political vacuum. The Celts of the south were attacked by tribes from the north and in their desperation sought help from abroad. There are parallels for this at other points in the history of the British Isles. Thus in the case of Ireland, help was sought by Irish chieftains from their Anglo-Norman neighbours in Wales in the late 12th century in their internal squabbles. This heralded the invasion of Ireland by the English. Equally with the Celts of the 5th century the help which they imagined would solve their internal difficulties turned out to be a boomerang which turned on them.

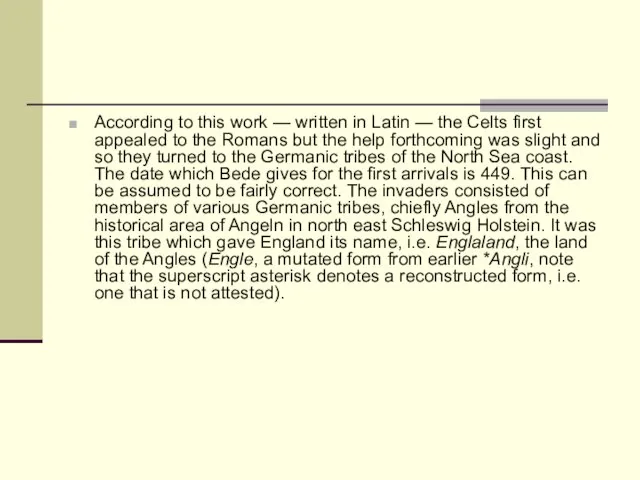

Слайд 46According to this work — written in Latin — the Celts first

appealed to the Romans but the help forthcoming was slight and so they turned to the Germanic tribes of the North Sea coast. The date which Bede gives for the first arrivals is 449. This can be assumed to be fairly correct. The invaders consisted of members of various Germanic tribes, chiefly Angles from the historical area of Angeln in north east Schleswig Holstein. It was this tribe which gave England its name, i.e. Englaland, the land of the Angles (Engle, a mutated form from earlier *Angli, note that the superscript asterisk denotes a reconstructed form, i.e. one that is not attested).

Слайд 47Other tribes represented in these early invasions were Jutes from the Jutland

peninsula (present-day mainland Denmark), Saxons from the area nowadays known as Niedersachsen (‘Lower Saxony’, but which is historically the original Saxony), the Frisians from the North Sea coast islands stretching from the present-day north west coast of Schleswig-Holstein down to north Holland. These are nowadays split up into North, East and West Frisian islands, of which only the North and the West group still have a variety of language which is definitely Frisian (as opposed to Low German or Dutch).

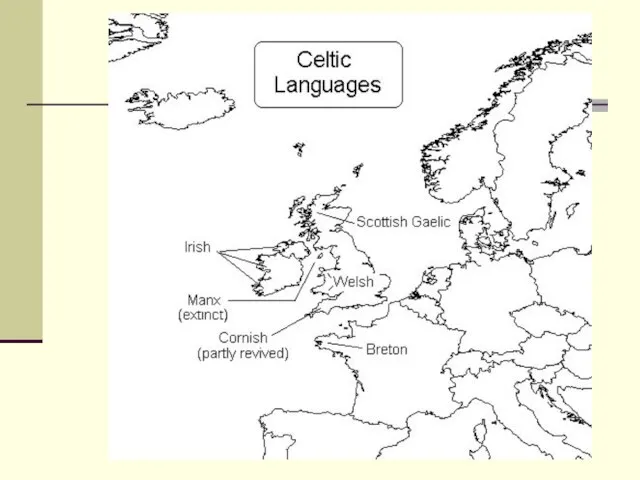

Слайд 48The indigeneous Celts of Britain were quickly pressed into the West of

England, Wales and Cornwall, and some crossed the Channel in the 5th and 6th centuries to Brittany and thus are responsible for a Celtic language — Breton — being spoken in France to this day, although Cornish, its counterpart in south-west England, died out in the 18th century

Слайд 49The Germanic areas which became established in the period following the initial

settlements consisted of the following seven ‘kingdoms': Kent, Essex, Sussex, Wessex, East Anglia, Mercia and Northumbria. These are known as the Anglo-Saxon Heptarchy. Political power was initially concentrated in the sixth century in Kent but this passed to Northumbria in the seventh and eighth centuries. After this a shift to the south began, first to Mercia in the ninth century and later on to West Saxony in the tenth and eleventh centuries

Слайд 50Old English ‘kingdoms’ around 800

Слайд 51Dialects of Old English

The dialects of Old English are more or

less co-terminous with the regional kingdoms. The various Germanic tribes brought their own dialects which were then continued in England. Thus we have a Northumbrian dialect (Anglian in origin), a Kentish dialect (Jutish in origin), etc. The question as to what degree of cohesion already existed between the Germanic dialects when they were still spoken on the continent is unclear. Scholars of the 19th century favoured a theory whereby English and Frisian formed an approximate linguistic unity. This postulated linguistic entity is variously called Anglo-Frisian and Ingvaeonic, after the name which Tacitus (c 55-120) in his Germania gave to the Germanic population settled on the North Sea coast. Towards the end of the Old English period the dialectal position becomes complicated by the fact that the West Saxon dialect achieved prominence as an inter-dialectal means of communication.

Порядок регистрации и получения патента на изобретение

Порядок регистрации и получения патента на изобретение Жизненный цикл человеческого капитала. Тема 3

Жизненный цикл человеческого капитала. Тема 3 Старинные меню

Старинные меню Менеджмент и предпринимательство в дизайне

Менеджмент и предпринимательство в дизайне фразеологизмы

фразеологизмы RISC-архитектуры(Reduced Instruction Set Computer)

RISC-архитектуры(Reduced Instruction Set Computer) Схемы учебно-тренировочного комплекса 211, отдельного железнодорожного батальона механизации

Схемы учебно-тренировочного комплекса 211, отдельного железнодорожного батальона механизации Фёдорова Наталья Петровна

Фёдорова Наталья Петровна Китай

Китай ГИПЕРМАРКЕТ________ В ВАШЕМ ГОРОДЕ

ГИПЕРМАРКЕТ________ В ВАШЕМ ГОРОДЕ Презентация на тему Реформы Петра в области образования

Презентация на тему Реформы Петра в области образования  Золотой век алхимии

Золотой век алхимии Педагогический совет

Педагогический совет 1 сентября - День знаний

1 сентября - День знаний Яндекс. Постконтекстная реклама

Яндекс. Постконтекстная реклама Презентация на тему Строение, свойства костей. Типы их соединения

Презентация на тему Строение, свойства костей. Типы их соединения Interesting holiday in Australia

Interesting holiday in Australia Правовые акты управления

Правовые акты управления Экологические проблемы Байкала

Экологические проблемы Байкала Колледж ландшафтного дизайна №18

Колледж ландшафтного дизайна №18 Связь справедливости взаимодействия с эмоциями участников (на примере политических выборов)

Связь справедливости взаимодействия с эмоциями участников (на примере политических выборов) My mind about School

My mind about School Получение атомарно-чистой поверхности германия методом ионного травления

Получение атомарно-чистой поверхности германия методом ионного травления Распознавание слов по вопросам, точное употребление слов в предложении

Распознавание слов по вопросам, точное употребление слов в предложении Структура организации РОСТок

Структура организации РОСТок Презентация на тему Язык разметки гипертекста HTML

Презентация на тему Язык разметки гипертекста HTML Поделки из ракушек, морских камней и шишек

Поделки из ракушек, морских камней и шишек Нестандартные способы продвижения интернет-сайта

Нестандартные способы продвижения интернет-сайта