Слайд 3Mexico’s internal situation

Heavy government spendings on social welfare programs and the

development of the petroleum industry in the mid- to late- 1970s → budget deficit

Budget deficit were financed with commercial banks loans

Heavy reliance on imports

“We need to import about 30 percent of our total consumption” (Jesus Silva Herzog)

Mexico's dependence on open U.S. trade

52% of Mexican exports went to the U.S.

Petroleum revenues form the major part of GDP

Pre-election period: new president in December, 1982

Capital flight → Currency devaluation → Inflation

Слайд 4External situation

The banking system was understress by 1982:

Fraudulent banking practices flourished

Many banks

went bankrupt

Some countries were under threat of default (Poland, Argentina)

Rising real interest rates

Loans contracted on variable interest rates in the 1970s now entailed heavy interest costs

Recession in the USA and then Europe

Reduction of demand for petroleum products in Mexico’s principal export markets

Oil price shoks

Decrease of export revenues

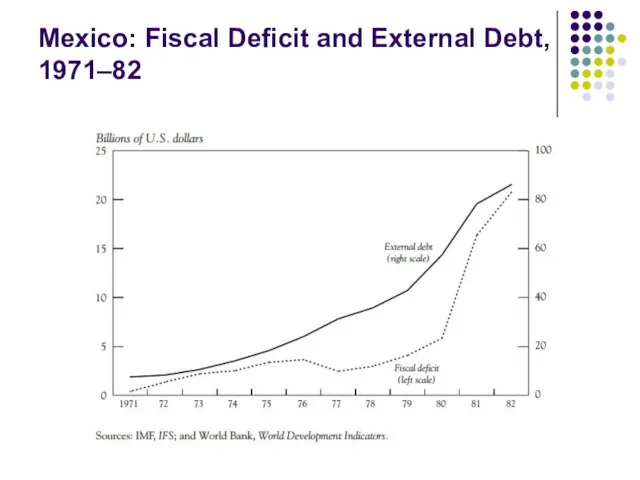

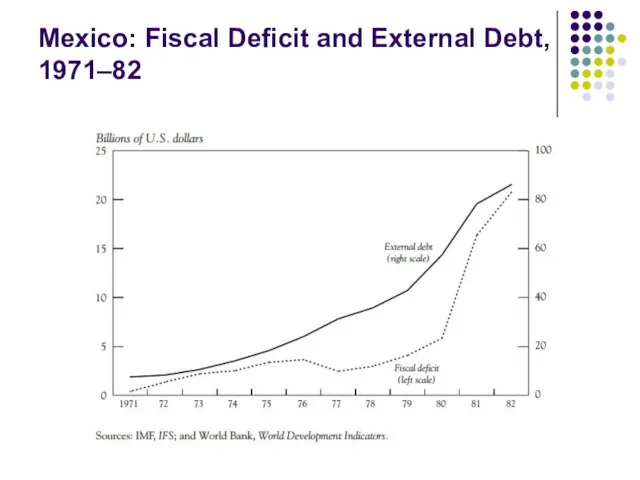

Слайд 5Mexico: Fiscal Deficit and External Debt, 1971–82

Слайд 6The USA-Mexico Interconnection

Mexican difficulties of any type are of great concern to

the USA

1,760-mile border ( > 2 832 km)

In 1982 -Mexico was the third largest trading partner of the USA

sold more oil to the United States than Saudi Arabia

purchased U.S. grain in quantities second only to Japan.

The United States provided two-thirds of Mexico's imports.

1981-1982 the U.S. trade balance with Mexico => from a $4 billion surplus to a $4 billion deficit.

US transactions with Mexico in the financial sector were substantial

U.S. commercial banks held an estimated 30% of Mexico's external debt

the debt was equivalent to 46% of the capital of the seventeen largest U.S. banks.

swap line with the U.S. Federal Reserve system—a testimony to the exceptional importance of Mexico to the U.S. economy.

the outflow of Mexican capital to the United States was significant.

In 1982, it was estimated that Mexicans had deposits in U.S. banks worth $14 billion, and that they owned an additional $30 billion of U.S. real estate.

Слайд 7The Washington Weekend

August 13-15, 1982

The Mexican Finance Minister, Jesus Silva Herzog, came

to the United States and warned of the impending danger of Mexican bankruptcy and a domino effect on the banks

Mexico risked bankruptcy by the end of the weekend if no solution was reached

The objective of the Mexican and U.S. governments was to arrange for interim financing to prevent a Mexican default until Mexico could reach agreement both with the IMF on an economic program and with its private creditors on a longer-term financial package.

Слайд 8The U.S. Federal Reserve Board

After the IMF's blessing Silva Herzog moved to

the U.S. Federal Reserve Board to meet Volcker

Volcker took three actions to facilitate resolution of Mexico's crisis.

1) estimated that Mexico would need $2 billion to avoid catastrophe on Monday morning, and suggested that the Mexican finance minister solicit this funding from the U.S. Treasury.

2) having acknowledged Mexico's need for some private bank debt relief Volcker urged Silva Herzog to arrange immediately with the private banks for a meeting at the New York Federal Reserve.

3) Volcker advised Silva Herzog to seek medium-term bridge loans from the central banks of Europe and Japan, so that Mexico could continue functioning while the IMF and private bank agreements were being arranged.

To arrange this funding, Volcker suggested a session at the BIS in Basel, Switzerland.

Слайд 9The U.S. Treasury Department

The set of negotiations that involved not only the

Treasury but the U.S. Departments of Agriculture, State, Energy, and Defense and the Office of Management and Budget (OMB)

Secretary Regan & deputy secretary R. T. McNamar

Silva Herzog and his team had both to convince U.S. Treasury leaders of the severity of Mexico's crisis and make lengthy, detailed presentations to apprise them of the latest Mexican economic developments.

Volcker and Silva Herzog's earlier $2 billion estimate of Mexico's immediate requirements was verified.

Слайд 10The first billion

The first billion was easily procured through the Department of

Agriculture.

Mexico was a large importer of food, and the United States, a surplus producer, had aided Mexico before with credits for food purchases.

Surplus U.S. grain and other products were available

The secretary of agriculture, John Brock had arranged through the Commodity Credit Corporation to extend more than $1 billion of guarantees to U.S. exporters for sales of agricultural commodities to Mexico.

Слайд 11The second billion

The second billion, by contrast, was raised only after extensive

U.S. maneuvering and a significant amount of conflict between U.S. and Mexican negotiators.

From the outset, the Americans and Mexicans had agreed that the most practical way to arrange emergency financing for Mexico was through some sort of exchange of U.S. money for Mexican oil.

The problem, however, was determining where in the U.S. government this money could be obtained on short notice.

the Social Security Fund

Exchange Stabilization Fund (ESF)

the Department of Energy => the Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR).

Слайд 12The second billion

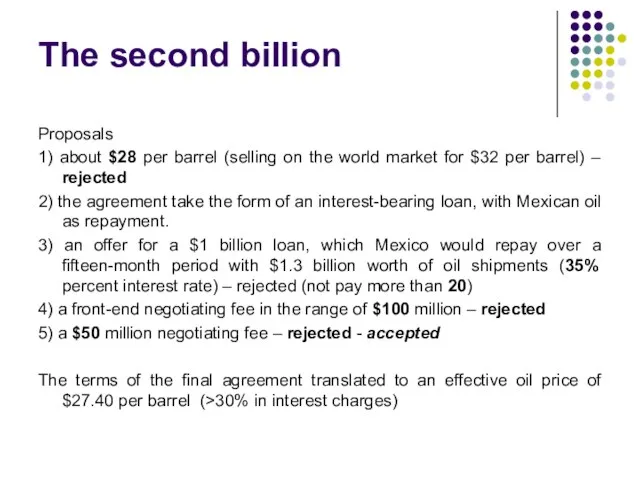

Proposals

1) about $28 per barrel (selling on the world market

for $32 per barrel) – rejected

2) the agreement take the form of an interest-bearing loan, with Mexican oil as repayment.

3) an offer for a $1 billion loan, which Mexico would repay over a fifteen-month period with $1.3 billion worth of oil shipments (35% percent interest rate) – rejected (not pay more than 20)

4) a front-end negotiating fee in the range of $100 million – rejected

5) a $50 million negotiating fee – rejected - accepted

The terms of the final agreement translated to an effective oil price of $27.40 per barrel (>30% in interest charges)

Слайд 13The BIS Loan

Representatives from the central banks of Belgium and Germany expressed

doubts about Lopez Portillo's ultimate willingness to accept IMF conditions in exchange for financial assistance.

The French representatives were equally reluctant, and the Europeans felt in general that Mexico was essentially an "American problem."

Under pressure from the U.S. Fed and Bank of England representatives, the Europeans agreed to provide 50% of a $1.5 billion bridge loan to Mexico.

The United States would supply the other 50%.

At the end of the session, Spain, as a gesture of support for its former colony, volunteered an additional $175 million. The United States matched that amount as well, bringing the total BIS loan to $1.85 billion.

Слайд 14The IMF’s interests

The threat of the possible international financial crisis

a Mexican default

→ the banks' solvency collapse

The crisis of the IMF as an institutition maintaining the world financial stability

→ Immidiate financial assistance to Mexico

Слайд 15The IMF’s behavior in negotiations

Immidiate actions

On the Washington Weekend WW the IMF

insisted that Mexico would have to immediately begin work toward developing an economic adjustment program

Reluctunce to change initial conditions

Pre-election period in Mexico → appointment of a new director of Mexico's CentralBank, an opponent of the IMF's programs

Diversification of risks

The U.S. government and the IMF also pressured commercial banks to participate in a loan to Mexico

Слайд 16The IMF

Outcomes

In December the IMF approved the adjustment program it had negotiated

with Mexico.

High adjustment by Mexico

(1) to reduce the budget deficit from 16.5% of GDP in 1982 to 8.5% in 1983, 5.5% in 1984, 3.5% in 1985, and near 0% in 1986;

(2) to phase out the triple exchange rate system and allow interest rates to rise;

(3) to increase the trade surplus to $8-10 billion;

(4) to reduce inflation;

(5) to cut the current account deficit.34

Some concessions from the banks

The banks, forced by the creditor governments and the IMF, also made real concessions to Mexico in the form of loans they were otherwise reluctant to make.

Слайд 17Commercial banks’ interests

About 1,400 commercial creditors

The large money-center banks ? stronger

incentives to continue lending

Large loans ? highly reliant on servicing from Mexico

European banks ? less enthusiastic about providing Mexico with new loans

The 10 largest American banks had a total exposure in Mexico of about $14 billion for both public and and private lending

Smaller banks ? reduction their losses

Mexican default would have bankrupted many lenders

Creditor governments showed no inclination to use force to help banks recover their money

Banks often reschedule loans in the hope of recouping their investments or simply cutting their losses

Слайд 18First Agreement with the Commercial Banks (August, 1982)

meeting between Mexico and the

chairmen of four major New York banks ? coordinating committee

meeting with representatives of 115 commercial banks ? 14 of the largest bank creditors, based in 8 different countries on 3 continents, adopted the proposal to establish an advisory committee to negotiate new loan agreements

IMF didn’t have enough resources to cover the borrowers’ financing requirements ? the Fund needed the help from banks

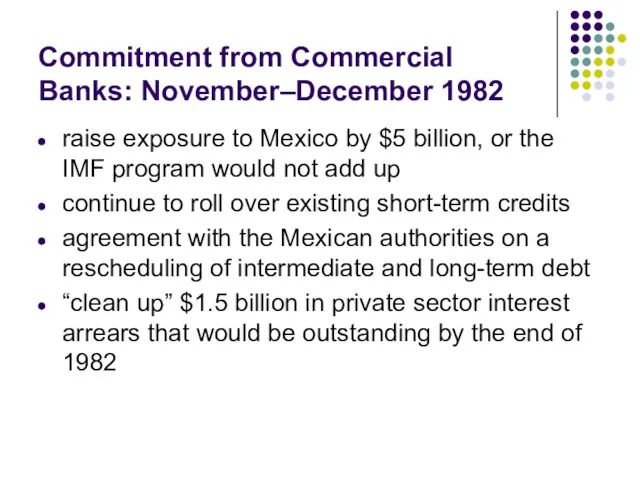

Слайд 19Commitment from Commercial Banks: November–December 1982

raise exposure to Mexico by $5 billion,

or the IMF program would not add up

continue to roll over existing short-term credits

agreement with the Mexican authorities on a rescheduling of intermediate and long-term debt

“clean up” $1.5 billion in private sector interest arrears that would be outstanding by the end of 1982

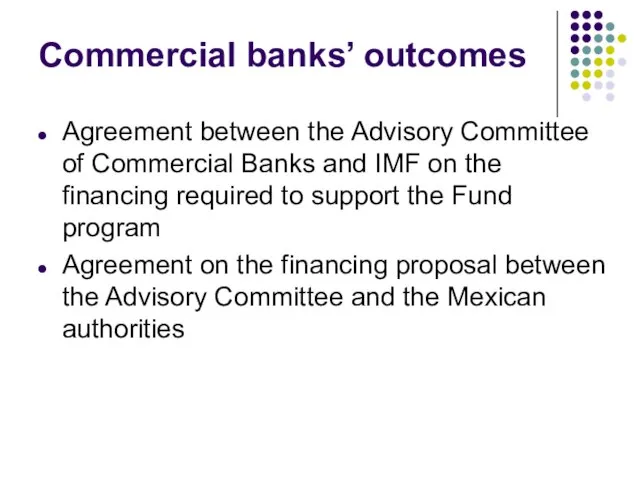

Слайд 20Commercial banks’ outcomes

Agreement between the Advisory Committee of Commercial Banks and IMF

on the financing required to support the Fund program

Agreement on the financing proposal between the Advisory Committee and the Mexican authorities

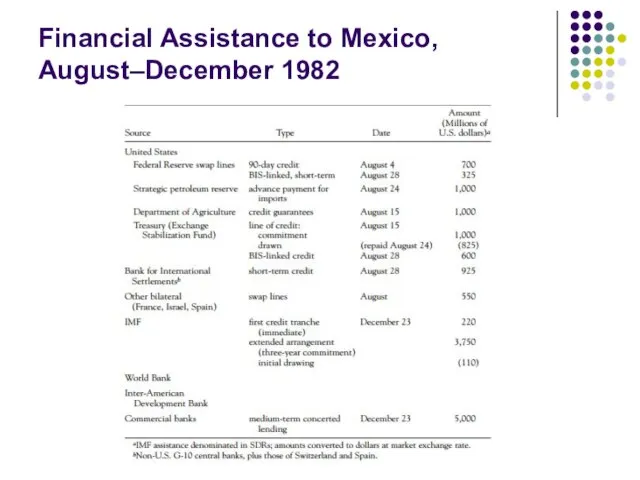

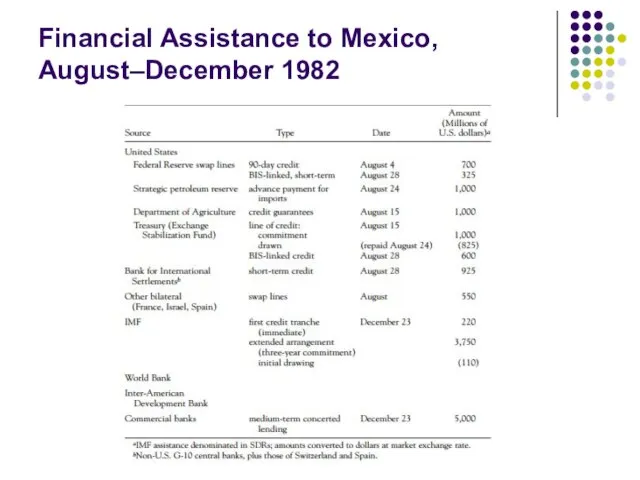

Слайд 21Financial Assistance to Mexico, August–December 1982

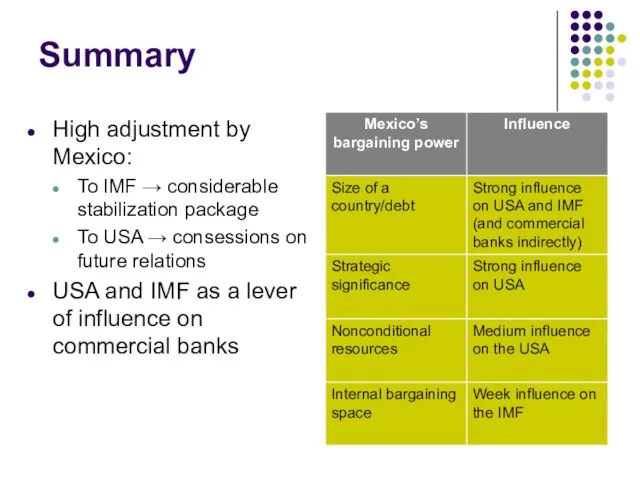

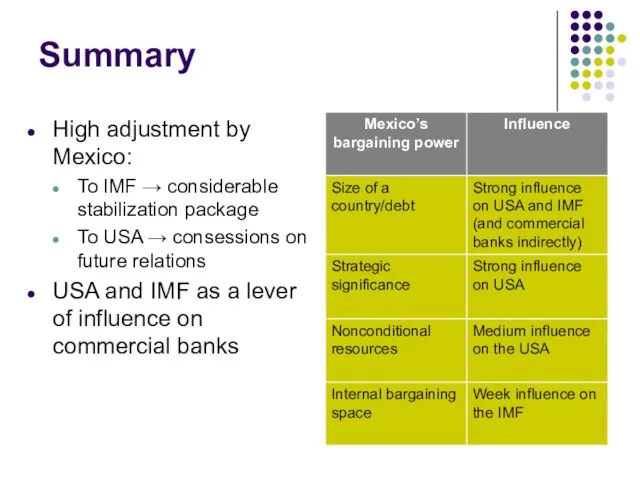

Слайд 22Summary

High adjustment by Mexico:

To IMF → considerable stabilization package

To USA → consessions

on future relations

USA and IMF as a lever of influence on commercial banks

FastReport Server и Firebirdкак достичь максимальной производительности

FastReport Server и Firebirdкак достичь максимальной производительности Синдром дефицита внимания и гиперактивности

Синдром дефицита внимания и гиперактивности Техника челночного бега

Техника челночного бега Роботизированное создание 3D моделей в реальном времени 3D SKY

Роботизированное создание 3D моделей в реальном времени 3D SKY Файловые системы

Файловые системы Информационно - технологическое обучение учащихся старших классов

Информационно - технологическое обучение учащихся старших классов Предметно-пространственная среда в эпоху ренессанса

Предметно-пространственная среда в эпоху ренессанса Перпендикулярность прямой и плоскости

Перпендикулярность прямой и плоскости  Отчёт депутата госдумы Шишкоедова В.М, партия Единая Россия

Отчёт депутата госдумы Шишкоедова В.М, партия Единая Россия Тема 13. Особенности регулирования труда отдельных категорий работников

Тема 13. Особенности регулирования труда отдельных категорий работников Нестандарты и креатив в интернет-рекламе

Нестандарты и креатив в интернет-рекламе Экстренная реанимационная помощь

Экстренная реанимационная помощь Кровотечение и методы его остановки

Кровотечение и методы его остановки Исследование и прогнозирование корреляционных зависимостей

Исследование и прогнозирование корреляционных зависимостей Льготы, предоставляемые военнослужащим, проходящим военную службу по призыву

Льготы, предоставляемые военнослужащим, проходящим военную службу по призыву Что ждет человечество?

Что ждет человечество? Свойства функций, непрерывных в ограниченной замкнутой области

Свойства функций, непрерывных в ограниченной замкнутой области  Светлоград 2009

Светлоград 2009 ВКР: Проектирование ремонтной прорези и грузового причала на Сеньковском перекате реки Оки

ВКР: Проектирование ремонтной прорези и грузового причала на Сеньковском перекате реки Оки Презентация на тему Наука и образование в Древней Греции

Презентация на тему Наука и образование в Древней Греции Москва – центр объединения русских земель.

Москва – центр объединения русских земель. Современные браузеры

Современные браузеры Визитная карточка школы

Визитная карточка школы Презентация на тему Стрессы и здоровье

Презентация на тему Стрессы и здоровье  Информационные системы управления проектами

Информационные системы управления проектами Литературная викторина По страницам любимых книг

Литературная викторина По страницам любимых книг Political systems of the world and the Nenets autonomous okrug

Political systems of the world and the Nenets autonomous okrug Презентация на тему Козьма Прутков

Презентация на тему Козьма Прутков