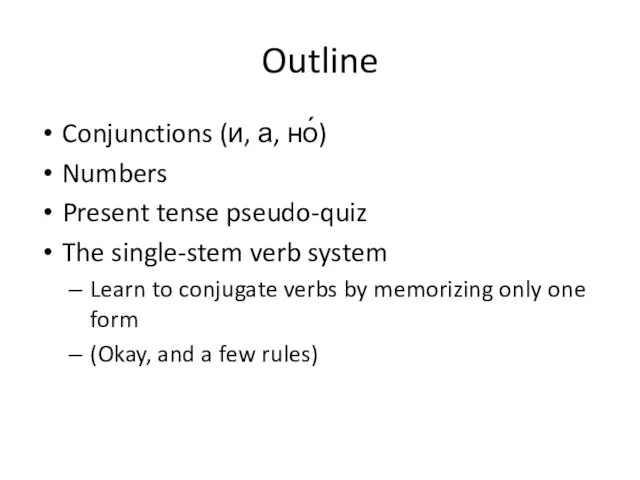

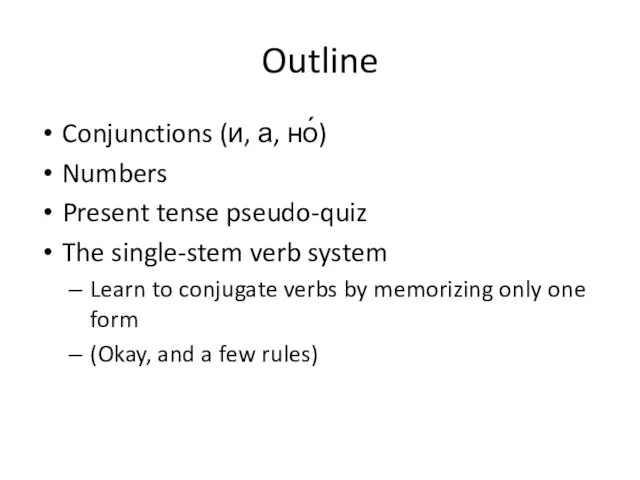

Слайд 2Outline

Conjunctions (и, а, но́)

Numbers

Present tense pseudo-quiz

The single-stem verb system

Learn to conjugate verbs

by memorizing only one form

(Okay, and a few rules)

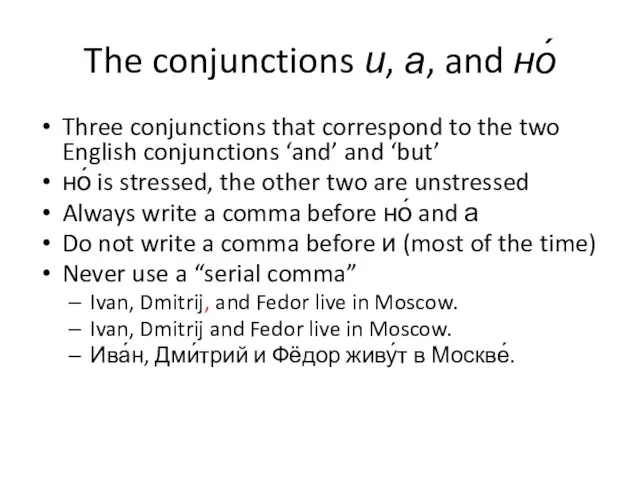

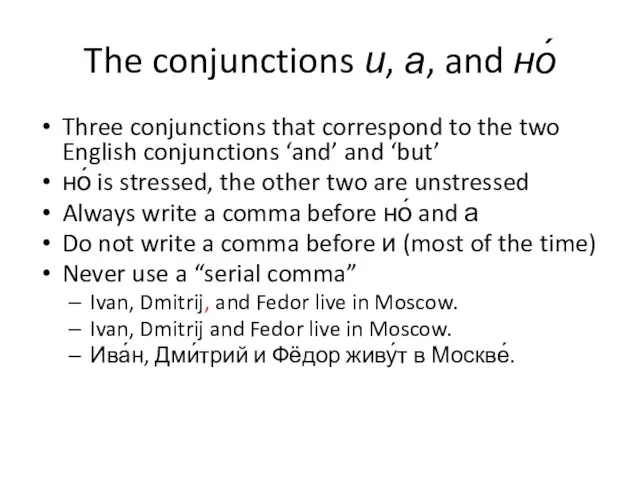

Слайд 3The conjunctions и, а, and но́

Three conjunctions that correspond to the two

English conjunctions ‘and’ and ‘but’

но́ is stressed, the other two are unstressed

Always write a comma before но́ and а

Do not write a comma before и (most of the time)

Never use a “serial comma”

Ivan, Dmitrij, and Fedor live in Moscow.

Ivan, Dmitrij and Fedor live in Moscow.

Ива́н, Дми́трий и Фёдор живу́т в Москве́.

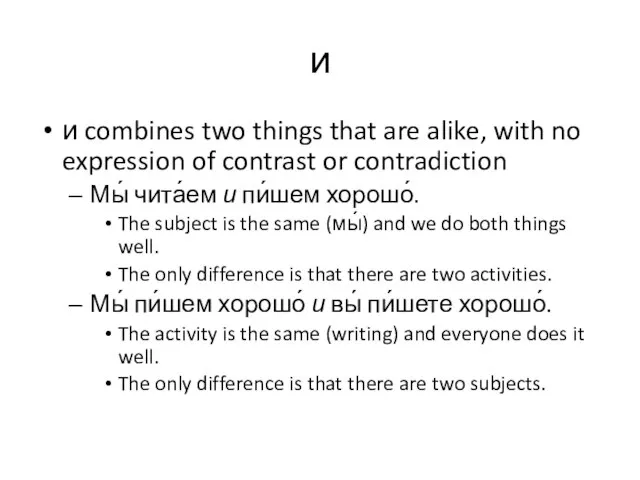

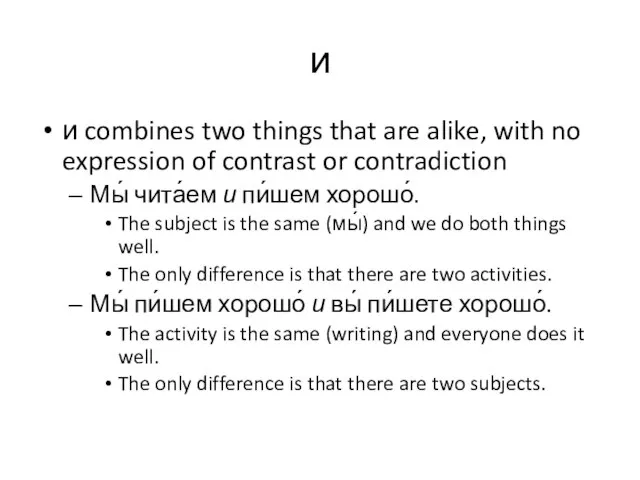

Слайд 4и

и combines two things that are alike, with no expression of contrast

or contradiction

Мы́ чита́ем и пи́шем хорошо́.

The subject is the same (мы́) and we do both things well.

The only difference is that there are two activities.

Мы́ пи́шем хорошо́ и вы́ пи́шете хорошо́.

The activity is the same (writing) and everyone does it well.

The only difference is that there are two subjects.

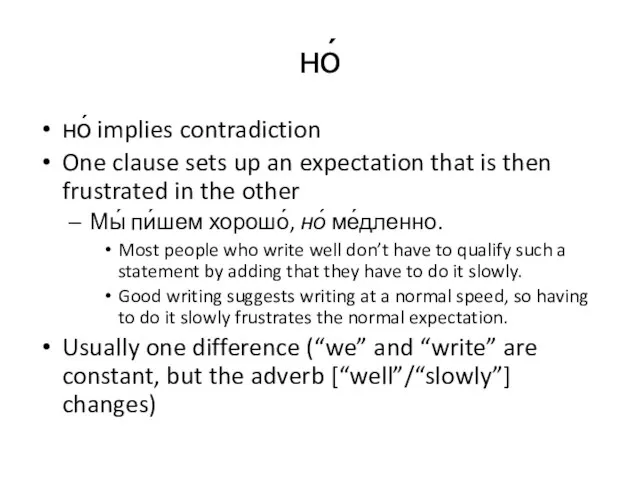

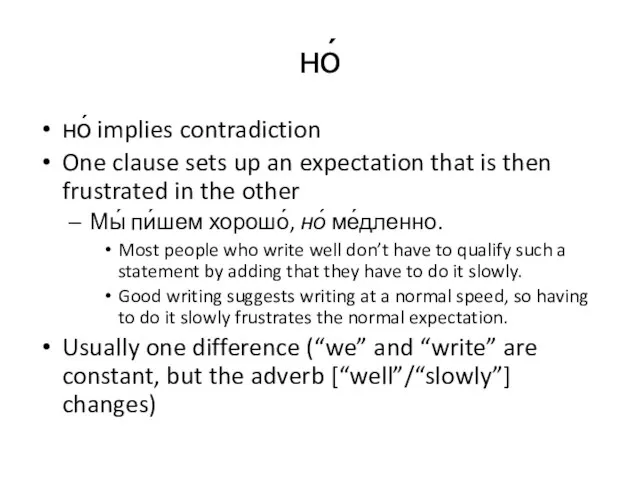

Слайд 5но́

но́ implies contradiction

One clause sets up an expectation that is then frustrated

in the other

Мы́ пи́шем хорошо́, но́ ме́дленно.

Most people who write well don’t have to qualify such a statement by adding that they have to do it slowly.

Good writing suggests writing at a normal speed, so having to do it slowly frustrates the normal expectation.

Usually one difference (“we” and “write” are constant, but the adverb [“well”/“slowly”] changes)

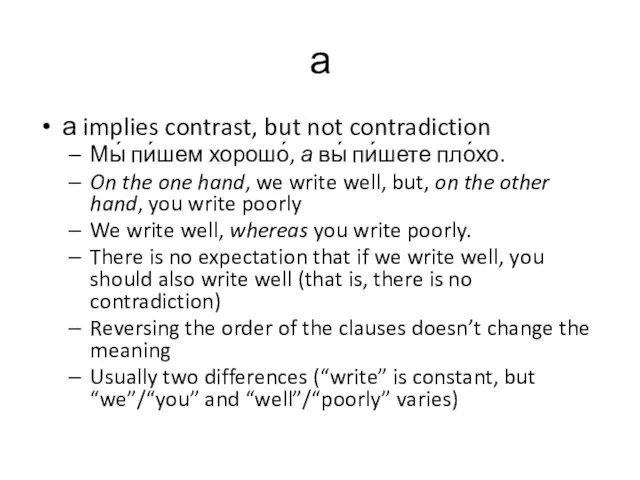

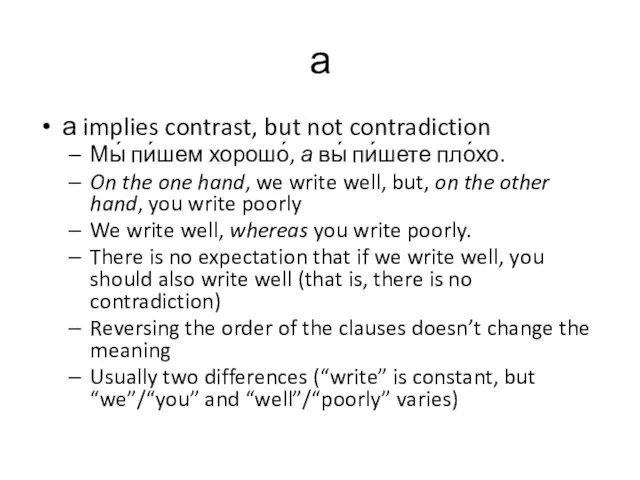

Слайд 6а

а implies contrast, but not contradiction

Мы́ пи́шем хорошо́, а вы́ пи́шете пло́хо.

On

the one hand, we write well, but, on the other hand, you write poorly

We write well, whereas you write poorly.

There is no expectation that if we write well, you should also write well (that is, there is no contradiction)

Reversing the order of the clauses doesn’t change the meaning

Usually two differences (“write” is constant, but “we”/“you” and “well”/“poorly” varies)

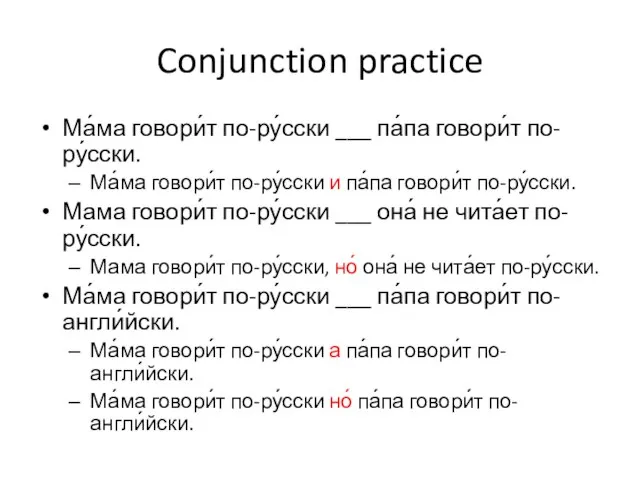

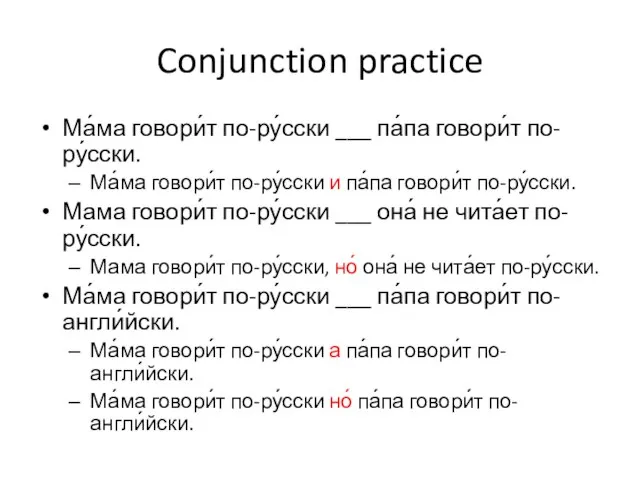

Слайд 7Conjunction practice

Ма́ма говори́т по-ру́сски ___ па́па говори́т по-ру́сски.

Ма́ма говори́т по-ру́сски и па́па

говори́т по-ру́сски.

Мама говори́т по-ру́сски ___ она́ не чита́ет по-ру́сски.

Мама говори́т по-ру́сски, но́ она́ не чита́ет по-ру́сски.

Ма́ма говори́т по-ру́сски ___ па́па говори́т по-англи́йски.

Ма́ма говори́т по-ру́сски а па́па говори́т по-англи́йски.

Ма́ма говори́т по-ру́сски но́ па́па говори́т по-англи́йски.

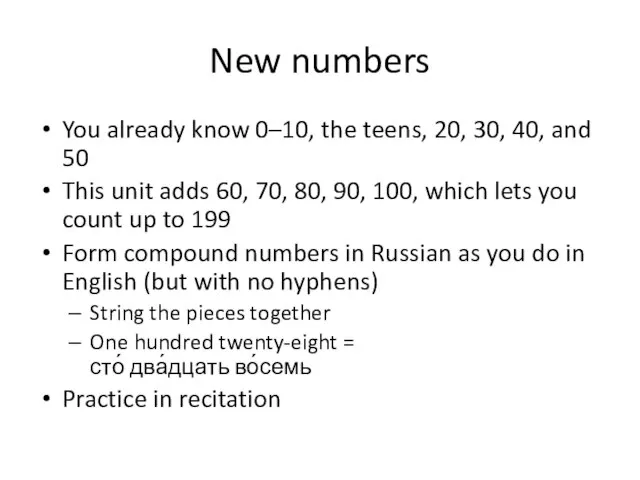

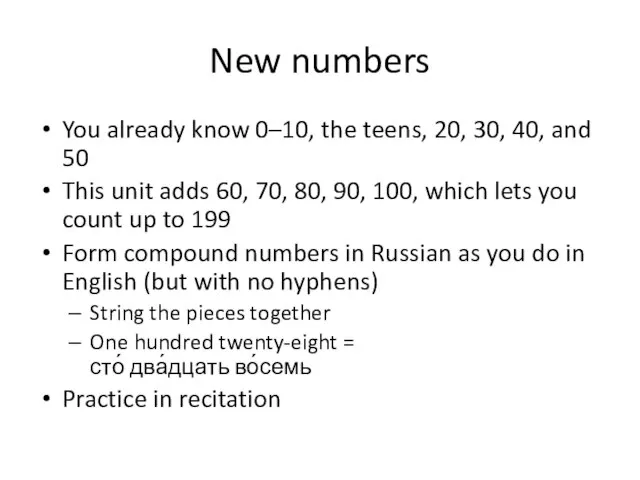

Слайд 8New numbers

You already know 0–10, the teens, 20, 30, 40, and 50

This

unit adds 60, 70, 80, 90, 100, which lets you count up to 199

Form compound numbers in Russian as you do in English (but with no hyphens)

String the pieces together

One hundred twenty-eight =

сто́ два́дцать во́семь

Practice in recitation

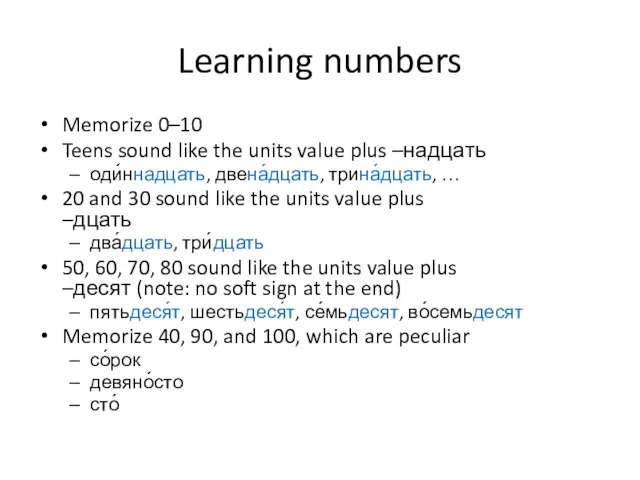

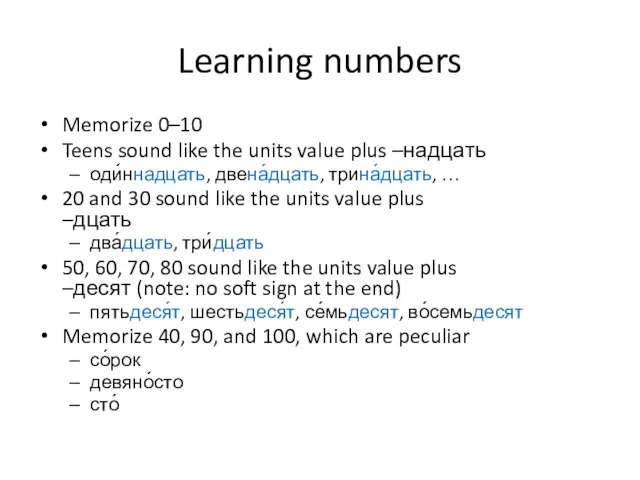

Слайд 9Learning numbers

Memorize 0–10

Teens sound like the units value plus –надцать

оди́ннадцать, двена́дцать, трина́дцать,

…

20 and 30 sound like the units value plus

–дцать

два́дцать, три́дцать

50, 60, 70, 80 sound like the units value plus

–десят (note: no soft sign at the end)

пятьдеся́т, шестьдеся́т, се́мьдесят, во́семьдесят

Memorize 40, 90, and 100, which are peculiar

со́рок

девяно́сто

сто́

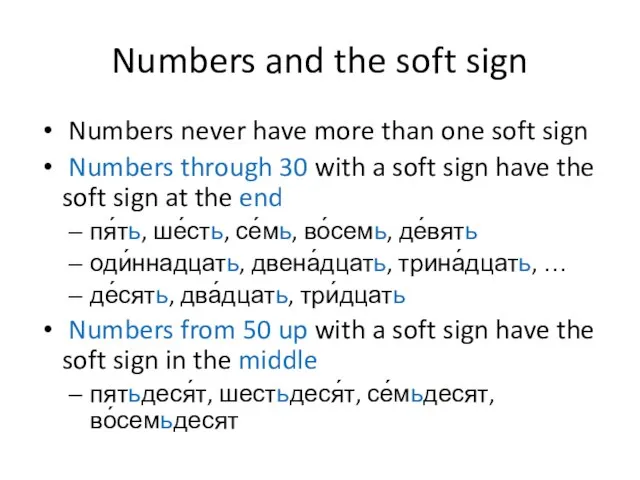

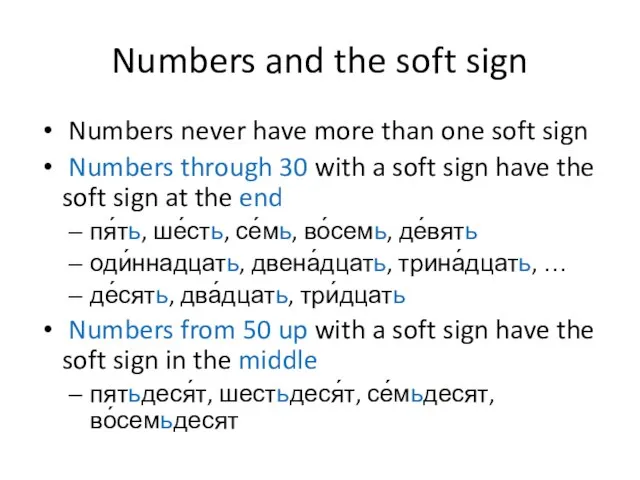

Слайд 10Numbers and the soft sign

Numbers never have more than one soft

sign

Numbers through 30 with a soft sign have the soft sign at the end

пя́ть, ше́сть, се́мь, во́семь, де́вять

оди́ннадцать, двена́дцать, трина́дцать, …

де́сять, два́дцать, три́дцать

Numbers from 50 up with a soft sign have the soft sign in the middle

пятьдеся́т, шестьдеся́т, се́мьдесят, во́семьдесят

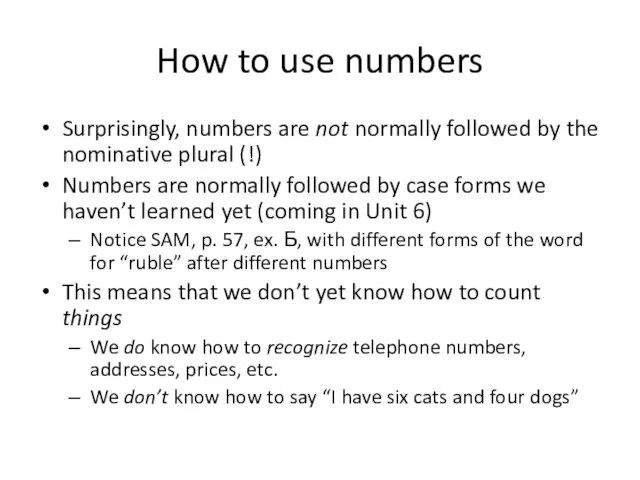

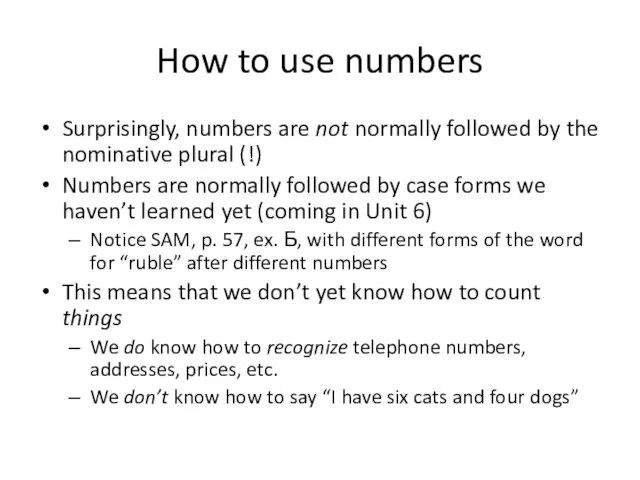

Слайд 11How to use numbers

Surprisingly, numbers are not normally followed by the nominative

plural (!)

Numbers are normally followed by case forms we haven’t learned yet (coming in Unit 6)

Notice SAM, p. 57, ex. Б, with different forms of the word for “ruble” after different numbers

This means that we don’t yet know how to count things

We do know how to recognize telephone numbers, addresses, prices, etc.

We don’t know how to say “I have six cats and four dogs”

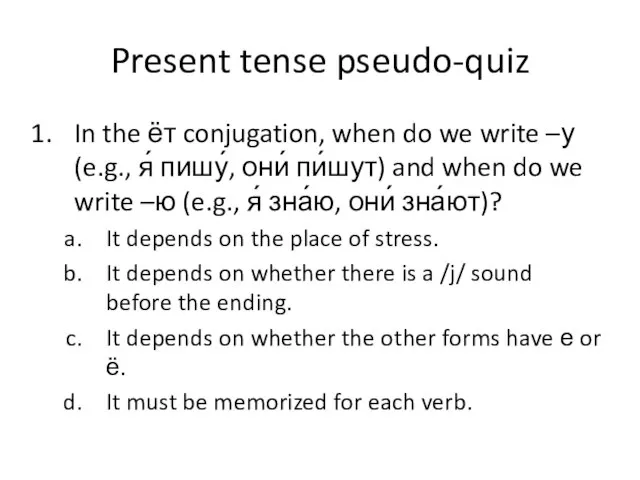

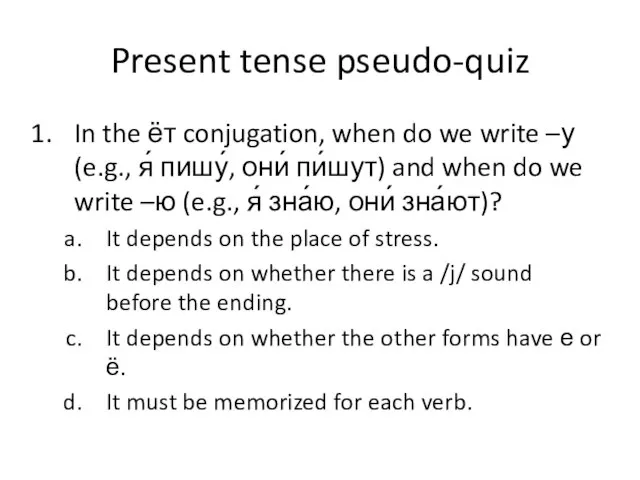

Слайд 12Present tense pseudo-quiz

In the ёт conjugation, when do we write –у (e.g.,

я́ пишу́, они́ пи́шут) and when do we write –ю (e.g., я́ зна́ю, они́ зна́ют)?

It depends on the place of stress.

It depends on whether there is a /j/ sound before the ending.

It depends on whether the other forms have е or ё.

It must be memorized for each verb.

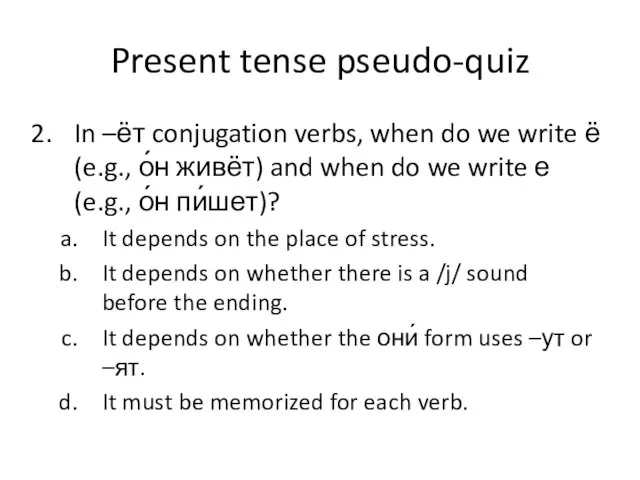

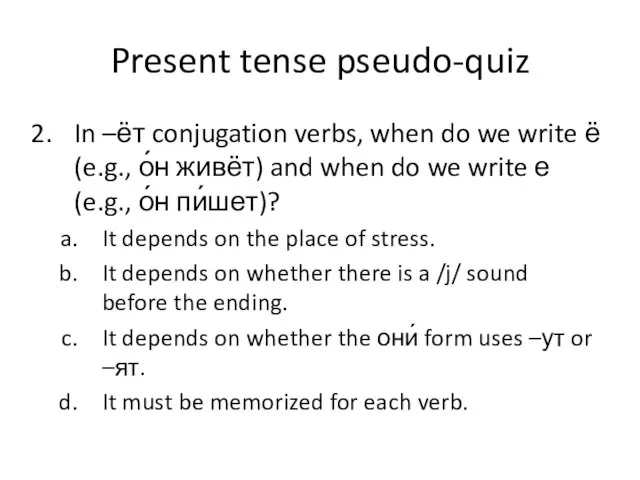

Слайд 13Present tense pseudo-quiz

In –ёт conjugation verbs, when do we write ё (e.g.,

о́н живёт) and when do we write е (e.g., о́н пи́шет)?

It depends on the place of stress.

It depends on whether there is a /j/ sound before the ending.

It depends on whether the они́ form uses –ут or –ят.

It must be memorized for each verb.

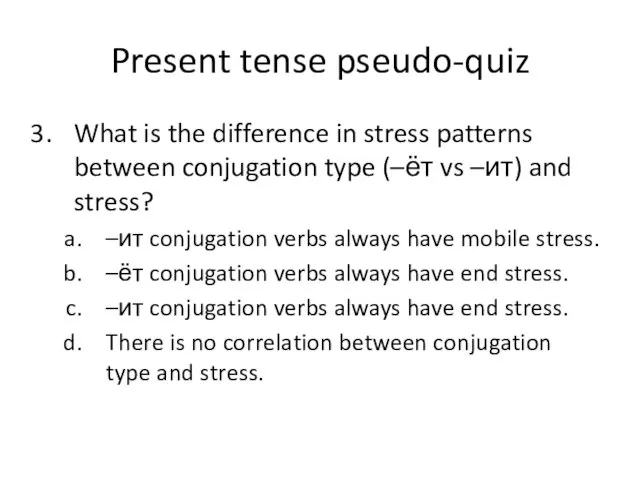

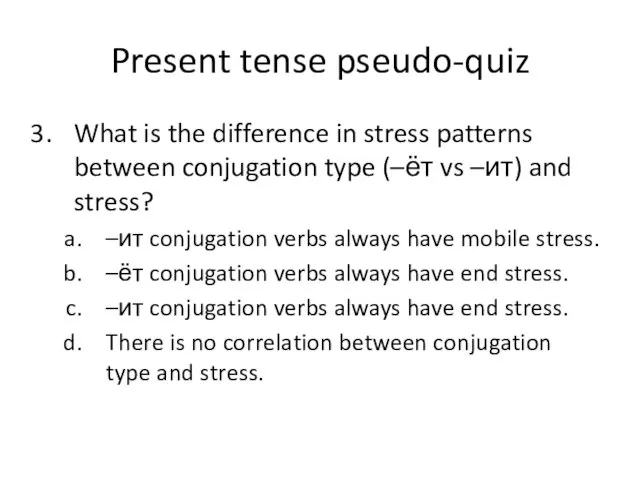

Слайд 14Present tense pseudo-quiz

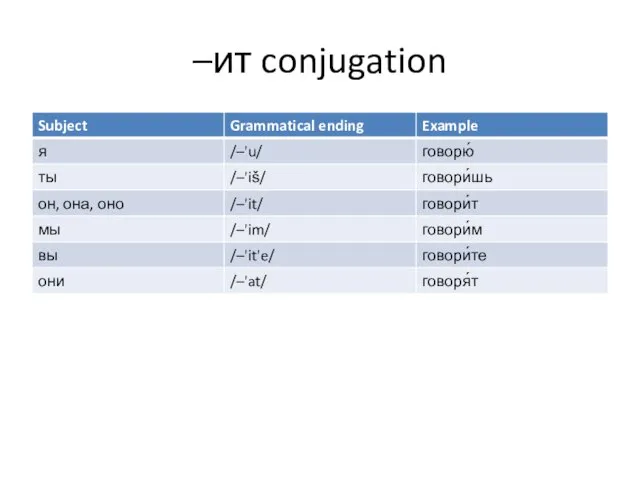

What is the difference in stress patterns between conjugation type

(–ёт vs –ит) and stress?

–ит conjugation verbs always have mobile stress.

–ёт conjugation verbs always have end stress.

–ит conjugation verbs always have end stress.

There is no correlation between conjugation type and stress.

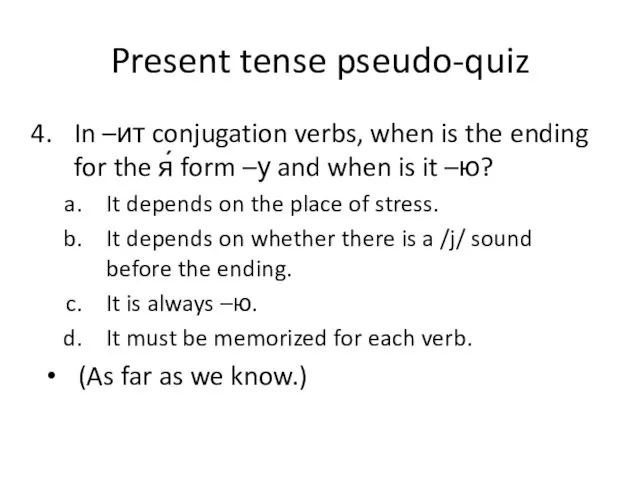

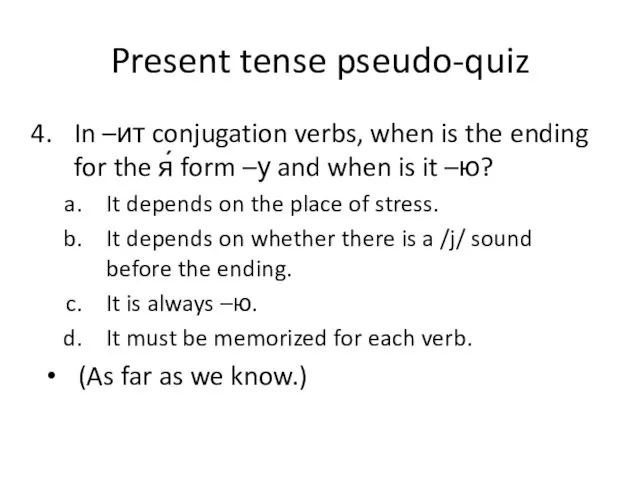

Слайд 15Present tense pseudo-quiz

In –ит conjugation verbs, when is the ending for the

я́ form –у and when is it –ю?

It depends on the place of stress.

It depends on whether there is a /j/ sound before the ending.

It is always –ю.

It must be memorized for each verb.

(As far as we know.)

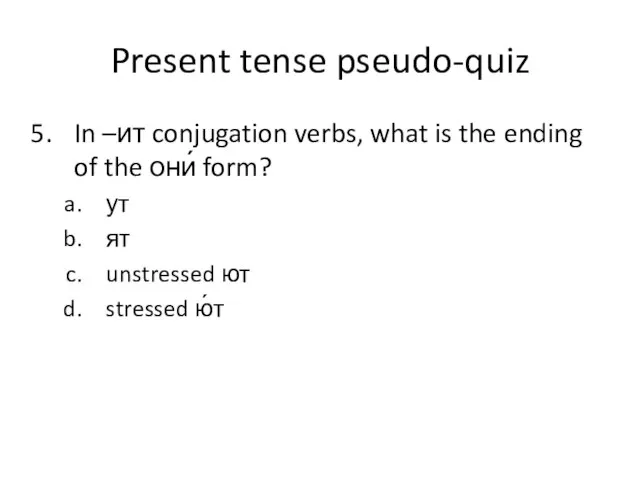

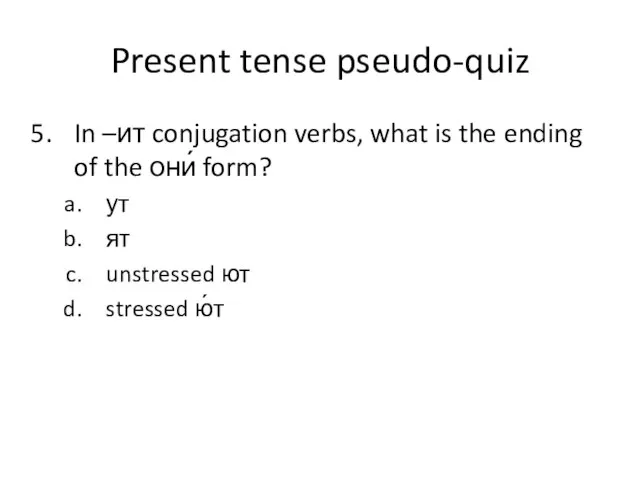

Слайд 16Present tense pseudo-quiz

In –ит conjugation verbs, what is the ending of the

они́ form?

ут

ят

unstressed ют

stressed ю́т

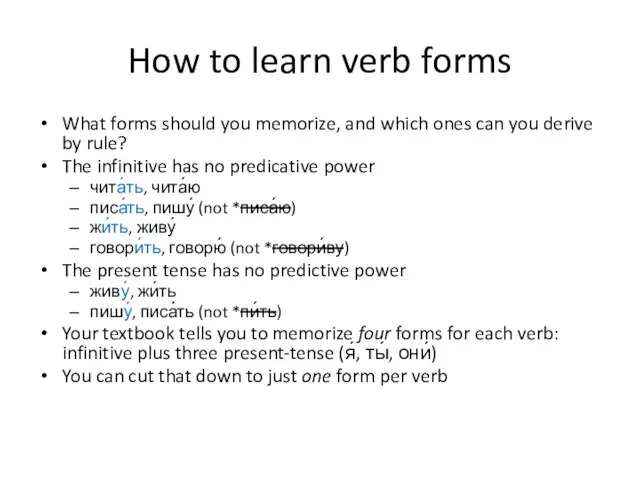

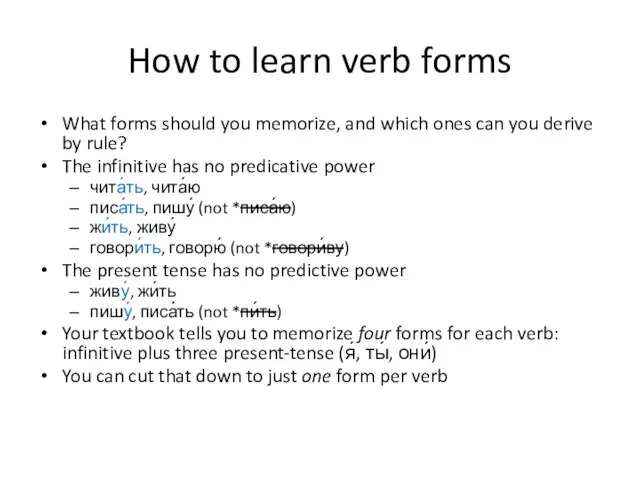

Слайд 17How to learn verb forms

What forms should you memorize, and which ones

can you derive by rule?

The infinitive has no predicative power

чита́ть, чита́ю

писа́ть, пишу́ (not *писа́ю)

жи́ть, живу́

говори́ть, говорю́ (not *говори́ву)

The present tense has no predictive power

живу́, жи́ть

пишу́, писа́ть (not *пи́ть)

Your textbook tells you to memorize four forms for each verb: infinitive plus three present-tense (я́, ты́, они́)

You can cut that down to just one form per verb

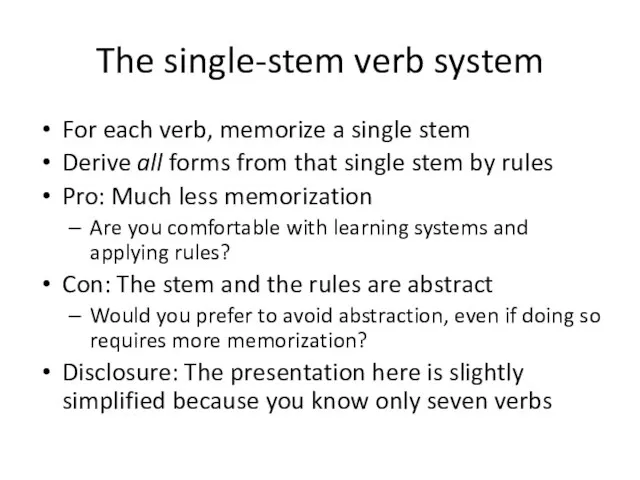

Слайд 18The single-stem verb system

For each verb, memorize a single stem

Derive all forms

from that single stem by rules

Pro: Much less memorization

Are you comfortable with learning systems and applying rules?

Con: The stem and the rules are abstract

Would you prefer to avoid abstraction, even if doing so requires more memorization?

Disclosure: The presentation here is slightly simplified because you know only seven verbs

Слайд 19Stems and endings

As with nouns and adjectives, think in terms of sounds,

not letters

Like nouns and adjectives, verb forms are made by combining stems and endings

Stems may end in consonant sounds or vowel sounds

Endings may begin with consonant sounds or vowel sounds

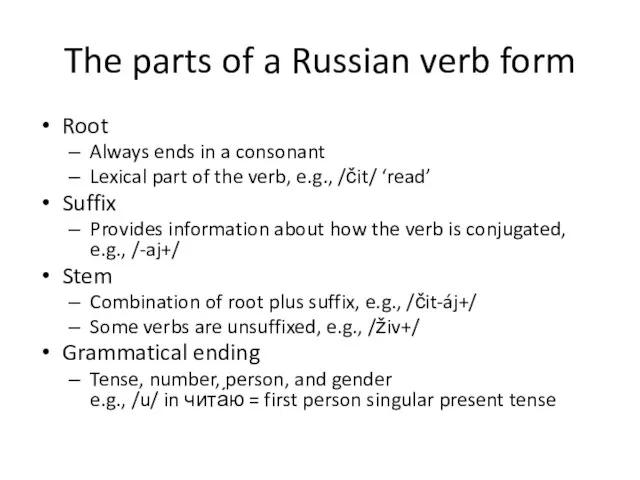

Слайд 21The parts of a Russian verb form

Root

Always ends in a consonant

Lexical part of the verb, e.g., /čit/ ‘read’

Suffix

Provides information about how the verb is conjugated, e.g., /-aj+/

Stem

Combination of root plus suffix, e.g., /čit-áj+/

Some verbs are unsuffixed, e.g., /živ+/

Grammatical ending

Tense, number, person, and gender

e.g., /u/ in чита́ю = first person singular present tense

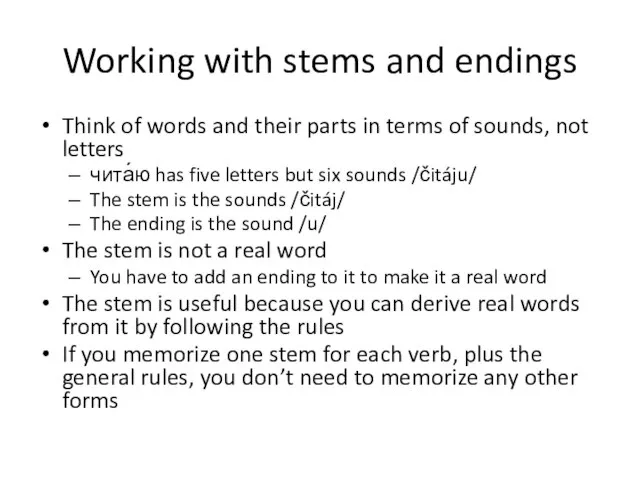

Слайд 22Working with stems and endings

Think of words and their parts in terms

of sounds, not letters

чита́ю has five letters but six sounds /čitáju/

The stem is the sounds /čitáj/

The ending is the sound /u/

The stem is not a real word

You have to add an ending to it to make it a real word

The stem is useful because you can derive real words from it by following the rules

If you memorize one stem for each verb, plus the general rules, you don’t need to memorize any other forms

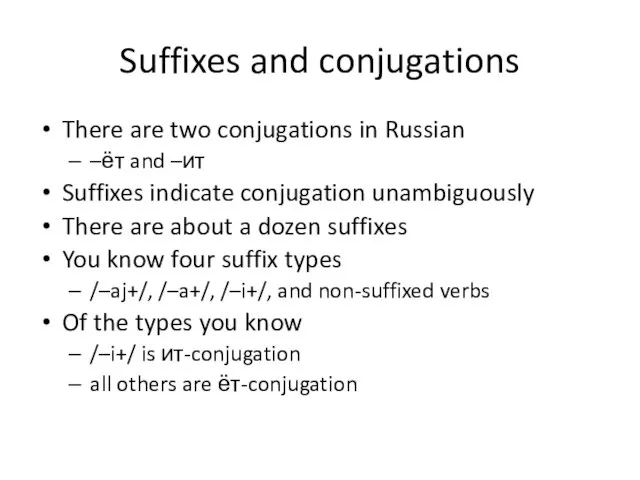

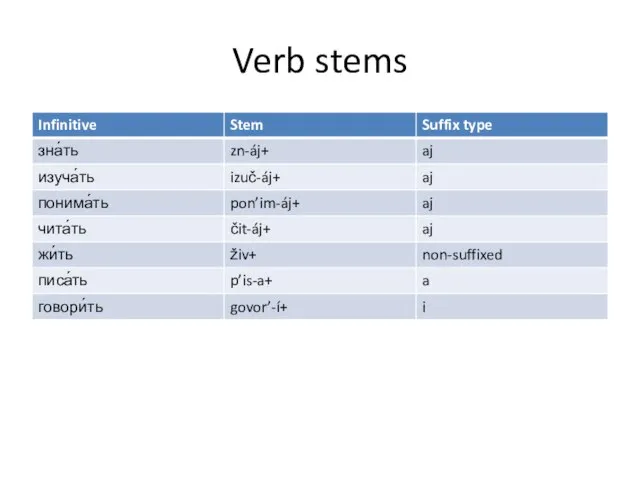

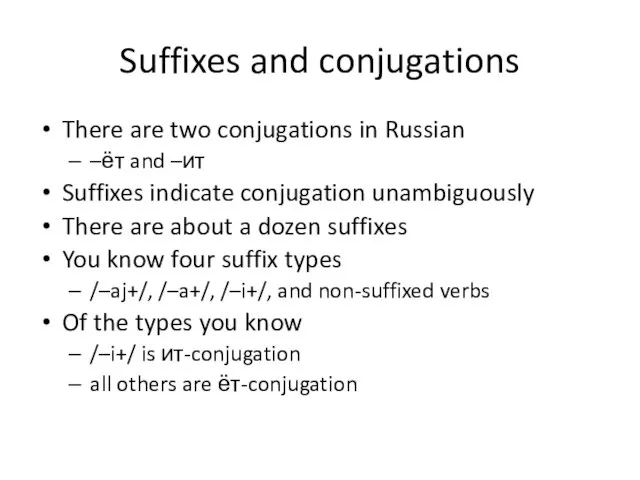

Слайд 23Suffixes and conjugations

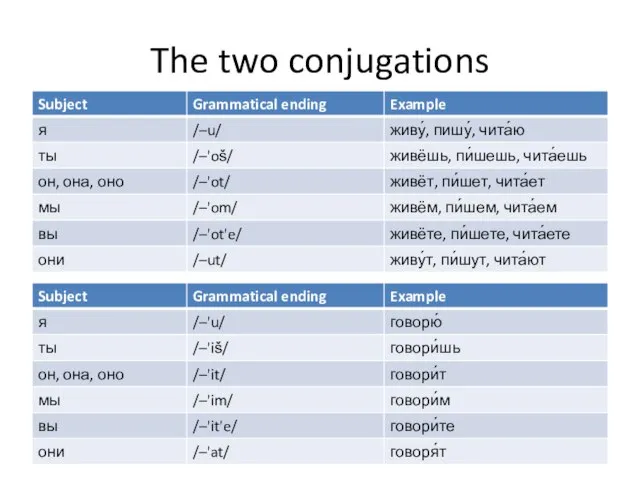

There are two conjugations in Russian

–ёт and –ит

Suffixes indicate conjugation

unambiguously

There are about a dozen suffixes

You know four suffix types

/–aj+/, /–a+/, /–i+/, and non-suffixed verbs

Of the types you know

/–i+/ is ит-conjugation

all others are ёт-conjugation

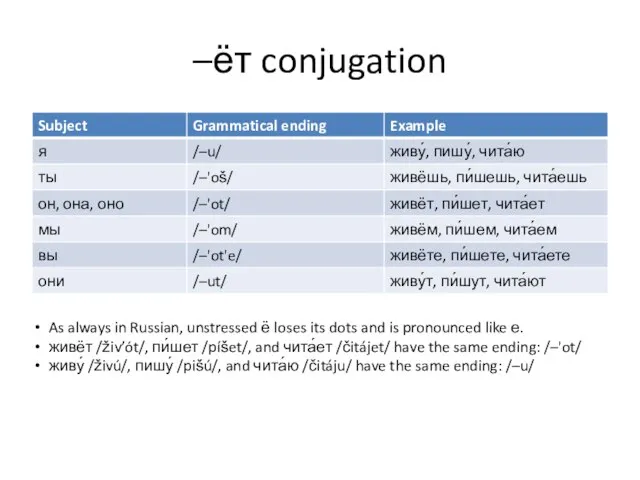

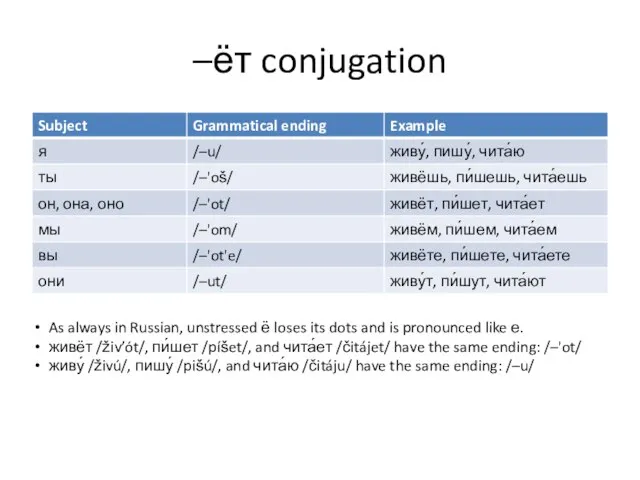

Слайд 24–ёт conjugation

As always in Russian, unstressed ё loses its dots and is

pronounced like е.

живёт /živ’ót/, пи́шет /píšet/, and чита́ет /čitájet/ have the same ending: /–'ot/

живу́ /živú/, пишу́ /pišú/, and чита́ю /čitáju/ have the same ending: /–u/

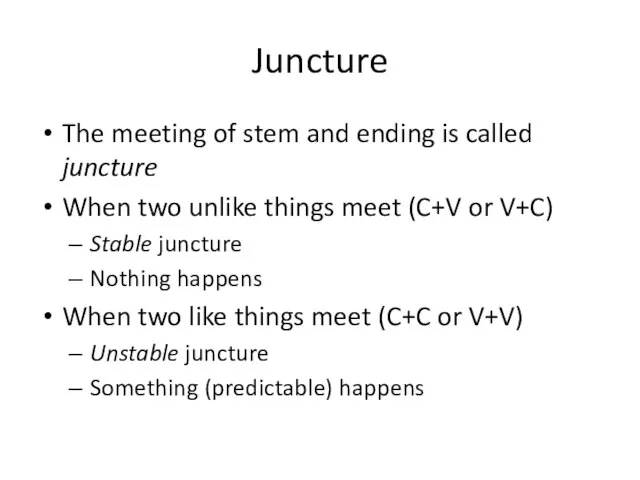

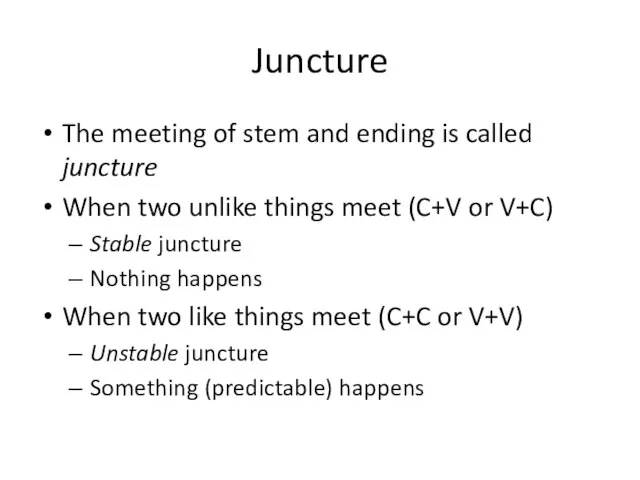

Слайд 27Juncture

The meeting of stem and ending is called juncture

When two unlike things

meet (C+V or V+C)

Stable juncture

Nothing happens

When two like things meet (C+C or V+V)

Unstable juncture

Something (predictable) happens

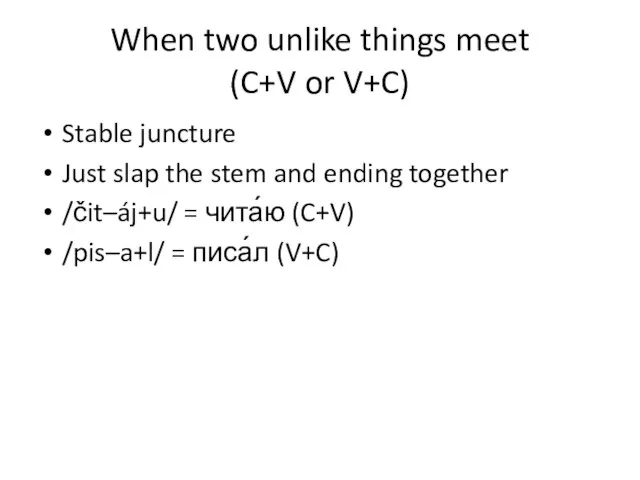

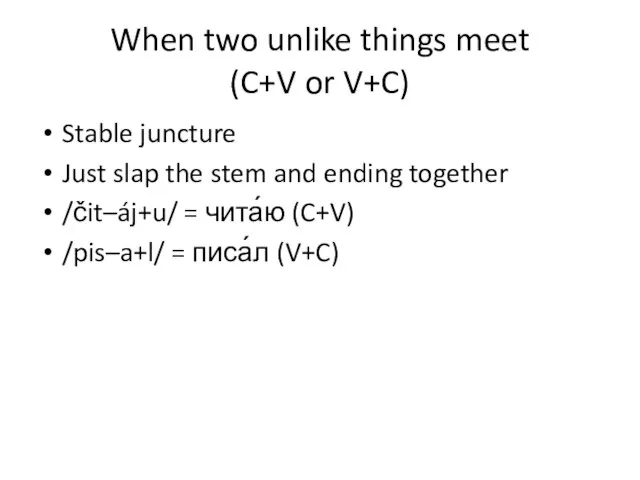

Слайд 28When two unlike things meet

(C+V or V+C)

Stable juncture

Just slap the stem and

ending together

/čit–áj+u/ = чита́ю (C+V)

/pis–a+l/ = писа́л (V+C)

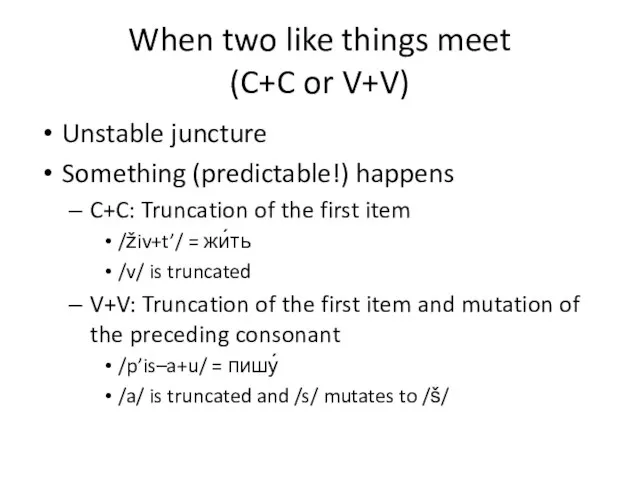

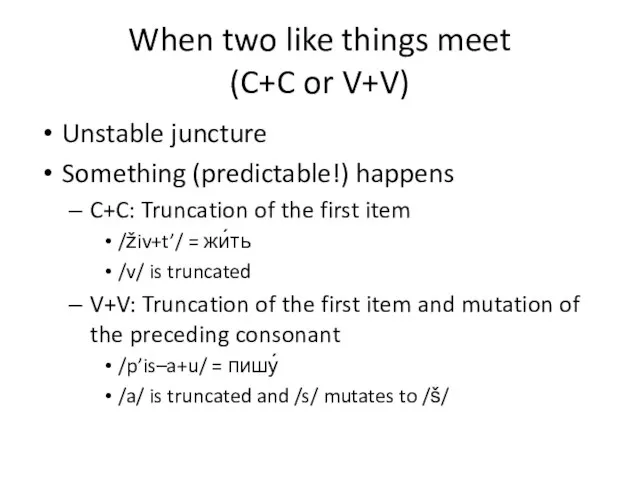

Слайд 29When two like things meet

(C+C or V+V)

Unstable juncture

Something (predictable!) happens

C+C: Truncation of

the first item

/živ+t’/ = жи́ть

/v/ is truncated

V+V: Truncation of the first item and mutation of the preceding consonant

/p’is–a+u/ = пишу́

/a/ is truncated and /s/ mutates to /š/

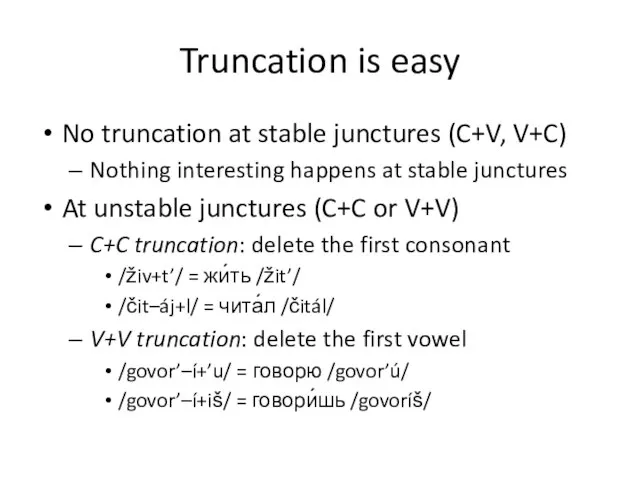

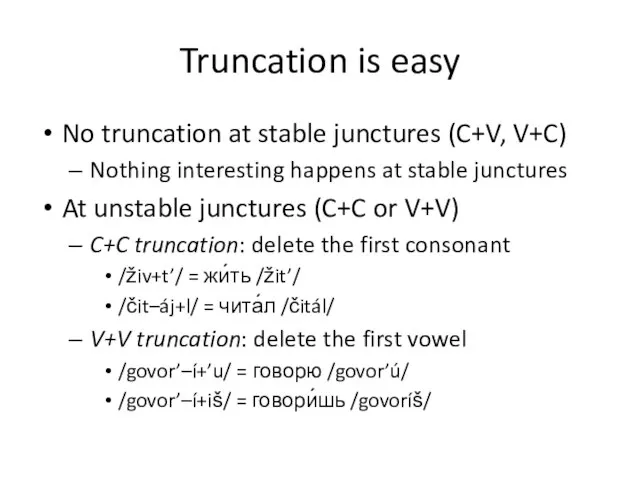

Слайд 30Truncation is easy

No truncation at stable junctures (C+V, V+C)

Nothing interesting happens at

stable junctures

At unstable junctures (C+C or V+V)

C+C truncation: delete the first consonant

/živ+t’/ = жи́ть /žit’/

/čit–áj+l/ = чита́л /čitál/

V+V truncation: delete the first vowel

/govor’–í+’u/ = говорю /govor’ú/

/govor’–í+iš/ = говори́шь /govoríš/

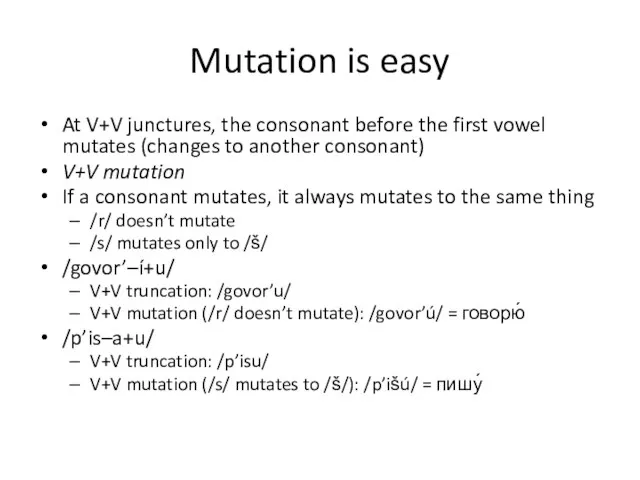

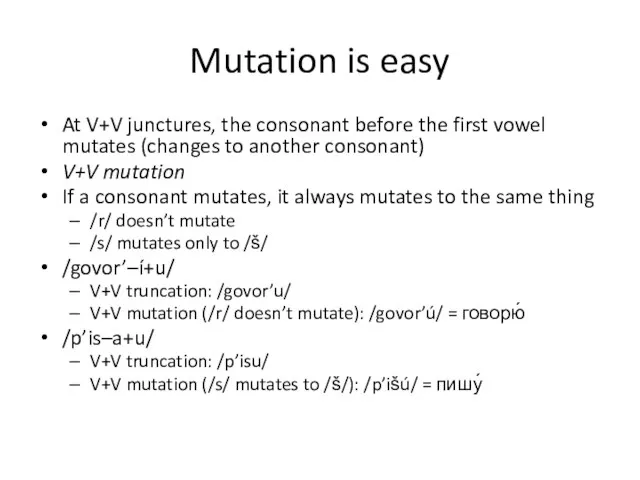

Слайд 31Mutation is easy

At V+V junctures, the consonant before the first vowel mutates

(changes to another consonant)

V+V mutation

If a consonant mutates, it always mutates to the same thing

/r/ doesn’t mutate

/s/ mutates only to /š/

/govor’–í+u/

V+V truncation: /govor’u/

V+V mutation (/r/ doesn’t mutate): /govor’ú/ = говорю́

/p’is–a+u/

V+V truncation: /p’isu/

V+V mutation (/s/ mutates to /š/): /p’išú/ = пишу́

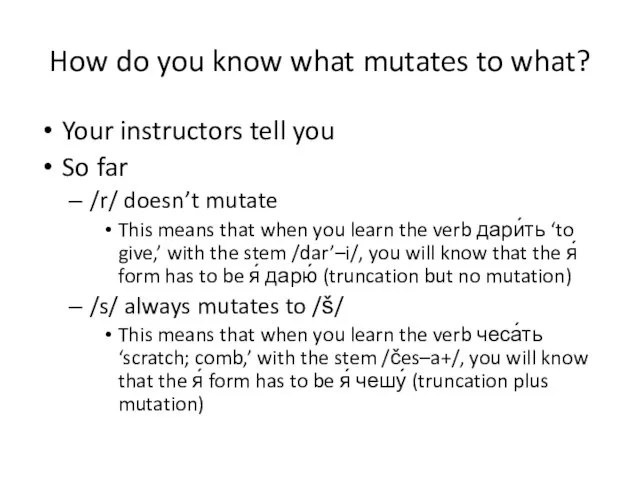

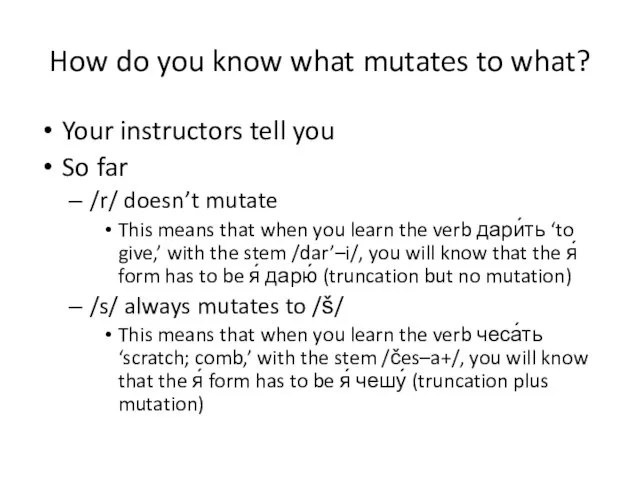

Слайд 32How do you know what mutates to what?

Your instructors tell you

So far

/r/

doesn’t mutate

This means that when you learn the verb дари́ть ‘to give,’ with the stem /dar’–i/, you will know that the я́ form has to be я́ дарю́ (truncation but no mutation)

/s/ always mutates to /š/

This means that when you learn the verb чеса́ть ‘scratch; comb,’ with the stem /čes–a+/, you will know that the я́ form has to be я́ чешу́ (truncation plus mutation)

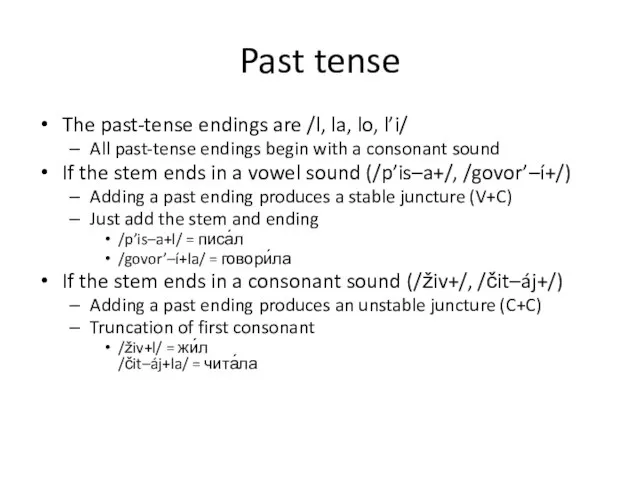

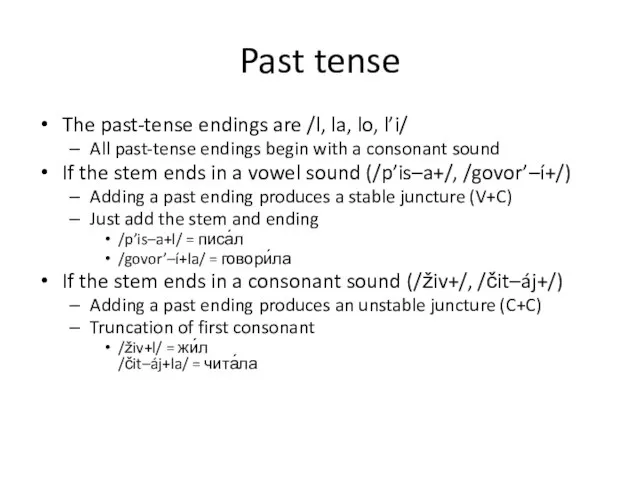

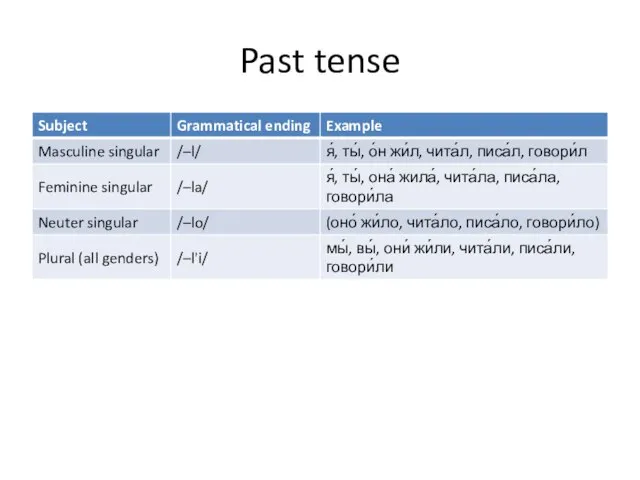

Слайд 33Past tense

The past-tense endings are /l, la, lo, l’i/

All past-tense endings begin

with a consonant sound

If the stem ends in a vowel sound (/p’is–a+/, /govor’–í+/)

Adding a past ending produces a stable juncture (V+C)

Just add the stem and ending

/p’is–a+l/ = писа́л

/govor’–í+la/ = говори́ла

If the stem ends in a consonant sound (/živ+/, /čit–áj+/)

Adding a past ending produces an unstable juncture (C+C)

Truncation of first consonant

/živ+l/ = жи́л

/čit–áj+la/ = чита́ла

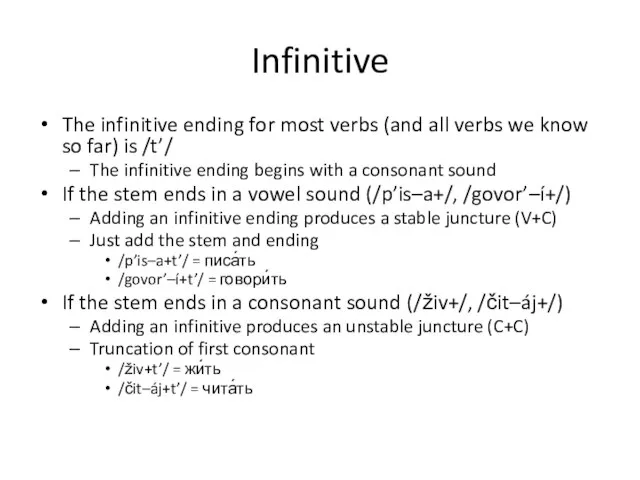

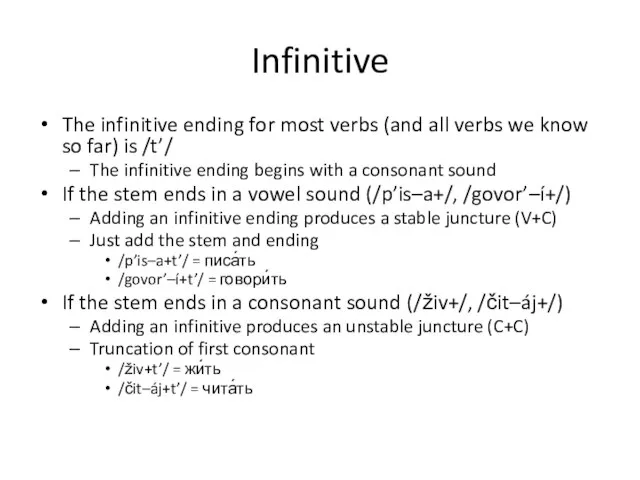

Слайд 35Infinitive

The infinitive ending for most verbs (and all verbs we know so

far) is /t’/

The infinitive ending begins with a consonant sound

If the stem ends in a vowel sound (/p’is–a+/, /govor’–í+/)

Adding an infinitive ending produces a stable juncture (V+C)

Just add the stem and ending

/p’is–a+t’/ = писа́ть

/govor’–í+t’/ = говори́ть

If the stem ends in a consonant sound (/živ+/, /čit–áj+/)

Adding an infinitive produces an unstable juncture (C+C)

Truncation of first consonant

/živ+t’/ = жи́ть

/čit–áj+t’/ = чита́ть

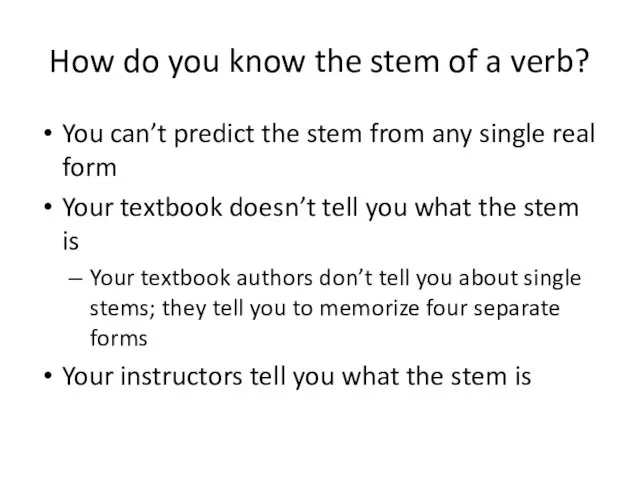

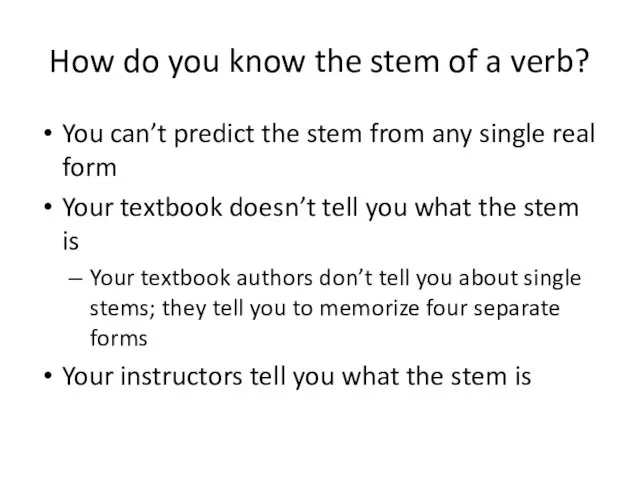

Слайд 36How do you know the stem of a verb?

You can’t predict the

stem from any single real form

Your textbook doesn’t tell you what the stem is

Your textbook authors don’t tell you about single stems; they tell you to memorize four separate forms

Your instructors tell you what the stem is

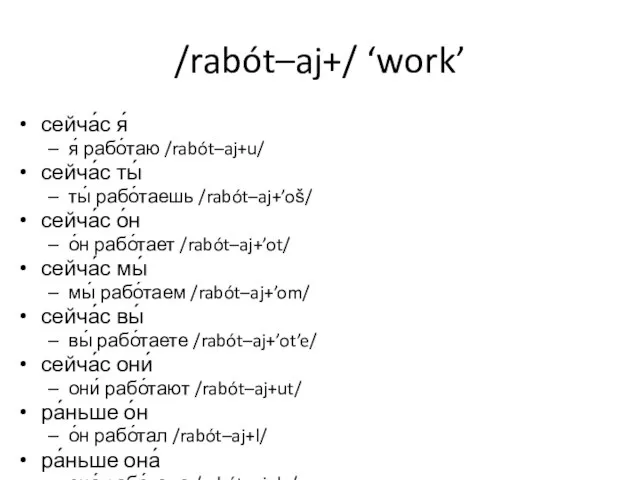

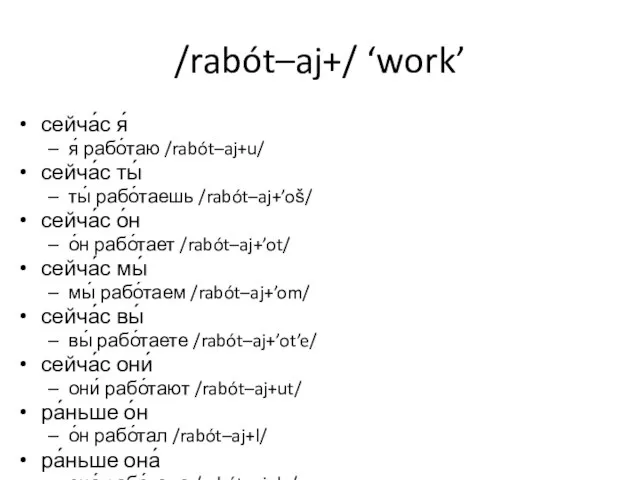

Слайд 37/rabót–aj+/ ‘work’

сейча́с я́

я́ рабо́таю /rabót–aj+u/

сейча́с ты́

ты́ рабо́таешь /rabót–aj+’oš/

сейча́с о́н

о́н рабо́тает

/rabót–aj+’ot/

сейча́с мы́

мы́ рабо́таем /rabót–aj+’om/

сейча́с вы́

вы́ рабо́таете /rabót–aj+’ot’e/

сейча́с они́

они́ рабо́тают /rabót–aj+ut/

ра́ньше о́н

о́н рабо́тал /rabót–aj+l/

ра́ньше она́

она́ рабо́тала /rabót–aj+la/

ра́ньше они́

они́ рабо́тали /rabót–aj+l’i/

Infinitive

рабо́тать /rabót–aj+t’/

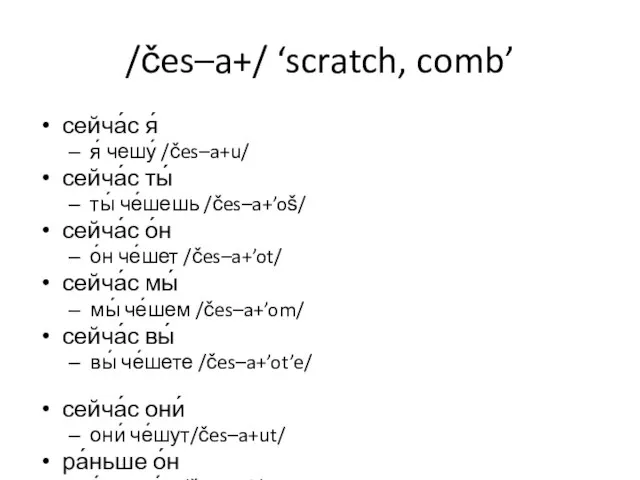

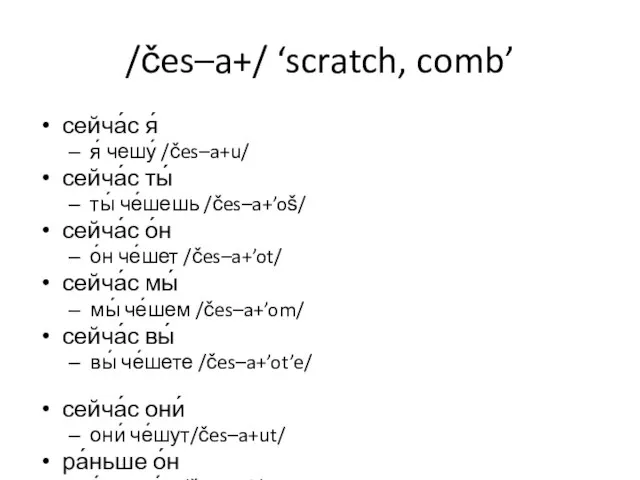

Слайд 38/čes–a+/ ‘scratch, comb’

сейча́с я́

я́ чешу́ /čes–a+u/

сейча́с ты́

ты́ че́шешь /čes–a+’oš/

сейча́с о́н

о́н

че́шет /čes–a+’ot/

сейча́с мы́

мы́ че́шем /čes–a+’om/

сейча́с вы́

вы́ че́шете /čes–a+’ot’e/

сейча́с они́

они́ че́шут/čes–a+ut/

ра́ньше о́н

о́н чеса́л /čes–a+l/

ра́ньше она́

она́ чеса́ла /čes–a+la/

ра́ньше они́

они́ чеса́ли /čes–a+l’i/

Infinitive

чеса́ть /čes–a+t’/

Метод фокальных объектов

Метод фокальных объектов ДОМЕННЫЕ ВОЙНЫ ПО-УКРАИНСКИ

ДОМЕННЫЕ ВОЙНЫ ПО-УКРАИНСКИ Продукция: Икра

Продукция: Икра Проблемно-поисковые образовательные технологии проблемное обучение метод проектов «мозговой штурм»

Проблемно-поисковые образовательные технологии проблемное обучение метод проектов «мозговой штурм» Конфликт и пути его решения

Конфликт и пути его решения Защита персональных данных в СКПК Председатель ВОСПКК «Вологда-Кредит» Петухова Надежда, к.э.н.14- 16 марта 2012 годаКонференци

Защита персональных данных в СКПК Председатель ВОСПКК «Вологда-Кредит» Петухова Надежда, к.э.н.14- 16 марта 2012 годаКонференци Банковское дело. Самарский Государственный Экономический Университет

Банковское дело. Самарский Государственный Экономический Университет Театр уж полон… Ложи блещут…

Театр уж полон… Ложи блещут… Инновативные технологии и цифровые трансформации в высшем образовании

Инновативные технологии и цифровые трансформации в высшем образовании Зрительные иллюзии

Зрительные иллюзии Актуальные вопросы функционирования розничных рынков электроэнергии

Актуальные вопросы функционирования розничных рынков электроэнергии Психологические особенности подросткового возраста

Психологические особенности подросткового возраста Презентация на тему Автомобильные семейки

Презентация на тему Автомобильные семейки  Женские образы в творчестве художников

Женские образы в творчестве художников Погода

Погода Intel

Intel Презентация на тему Моделирование ввода данных, разработка экспериментальных прогонов программы и её проверка

Презентация на тему Моделирование ввода данных, разработка экспериментальных прогонов программы и её проверка История русской одежды

История русской одежды Примеры постановки цели реализации целеполагания в компаниях, производящих газировку и соки

Примеры постановки цели реализации целеполагания в компаниях, производящих газировку и соки МОУ «Кужмарская средняя общеобразовательная школа» Звениговского района Республики Марий Эл

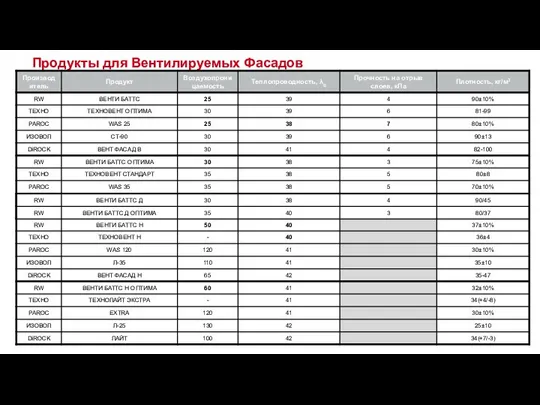

МОУ «Кужмарская средняя общеобразовательная школа» Звениговского района Республики Марий Эл Продукты для Вентилируемых Фасадов

Продукты для Вентилируемых Фасадов Электронные образовательные ресурсы.Практика применения в учебно-воспитательном процессе

Электронные образовательные ресурсы.Практика применения в учебно-воспитательном процессе Индукционный лаг ИЭЛ-2М

Индукционный лаг ИЭЛ-2М Развитие рынка SaaS решений в телекоме

Развитие рынка SaaS решений в телекоме Компания ЧТУП БелТоргХолод поставщик торгового и технологического оборудования для компаний в сегменте Фаст-фуд

Компания ЧТУП БелТоргХолод поставщик торгового и технологического оборудования для компаний в сегменте Фаст-фуд Клубный час Как вести себя за столом? Основы столового этикета

Клубный час Как вести себя за столом? Основы столового этикета ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЕ АГЕНТСТВО ПО ТЕХНИЧЕСКОМУ РЕГУЛИРОВАНИЮ И МЕТРОЛОГИИ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ДОПОЛНИТЕЛЬНОГО П

ФЕДЕРАЛЬНОЕ АГЕНТСТВО ПО ТЕХНИЧЕСКОМУ РЕГУЛИРОВАНИЮ И МЕТРОЛОГИИ ГОСУДАРСТВЕННОЕ ОБРАЗОВАТЕЛЬНОЕ УЧРЕЖДЕНИЕ ДОПОЛНИТЕЛЬНОГО П Совет сторонников Всероссийской политической партии Единая Россия Миасского городского округа. Моя любимая работа

Совет сторонников Всероссийской политической партии Единая Россия Миасского городского округа. Моя любимая работа